Administrators’ perspectives on teachers breaking contract at international schools

- 1Faculty of Education, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON, Canada

- 2School of Education, St. Thomas University, Fredericton, NB, Canada

This study on breaking contract at international schools provides insights from interviews with 13 international school administrators. Through an examination of the reasons for, and impacts of, breaking contract, five types of international school contract non-completion are identified. In addition to a typology for future studies of this phenomenon, the study outlines five impacts of contract non-completion and four key domains for school leaders to consider in relation to contract non-completion at international schools.

Introduction

It was about the fifth or sixth week of term… and we were worried. So we went round to the apartment and banged on the door. There was no reply. My colleague then said, “Hang on, I’ve just got a message,” and the message was: “I’m at the airport. We’re leaving.” We went into the apartment because we had a key, and in the apartment there were breakfast things on the table. The kid’s teddy bear was still sitting on the bed.

On the international school circuit, everyone has heard a story like this. The expression “they did a midnight run” is common parlance, and “midnight runner” refers to a teacher who one day fails to appear at school, without notice or warning, and never returns. The impact of such a decision ripples through the community. Administrators, colleagues, students, and parents can be left with a number of questions, and few answers, because when teachers do a midnight run their stories are seldom heard.

We enter into this research as former international school teachers who are familiar with the story of the midnight runner and as educational researchers who were unable to find empirical work on this phenomenon. Interested in the perspectives of both the teachers who leave and those who hire them, we designed a small-scale study to inquire into the dimensions of this experience and open a research conversation about breaking contract at international schools. Within this inquiry, we recognize that not all stories of leaving are those of the midnight run and have framed the study to explore the phenomenon of contract non-completion so that we might capture different types of leaving, whenever or however that might occur.

The overall focus of our study was to explore this phenomenon from dual perspectives: from administrators whose schools had teachers leave before the end of the school year as well as the educators who decided to leave their overseas positions. We aimed to attain insights that might help both educators and researchers know more about contract non-completion in international teaching contexts. We continue to be particularly interested in the personal and professional factors that influence international school teachers’ decisions to leave, and how both teachers and administrators describe the impacts of such a choice. In this paper, we report on the findings from the first of these participant groups—administrators.

International school teacher recruitment

Within the context of international schools, several terms are used to describe those who are in school administration or leadership positions. Terms such as school leaders, heads, directors, principals, or recruiters can all refer to those who are in leadership or administrative roles at international schools and who are also often responsible for hiring new teachers. While we recognize the diversity of terms that are used within the international school context, for the purposes of this paper we use the terms administrator and recruiter interchangeably to simplify the many titles that might indicate an individual who is in a school leadership position and is responsible for hiring new staff.

The international school industry is a steadily growing educational market, with over 13,400 private fee-paying schools and an estimated $53 billion in tuition fees (ISC Research, 2023). A global teacher shortage (UNESCO, 2023) is impacting all sectors, and with nearly 8 million students globally, teacher recruitment and retention is a unique challenge for international schools, which are typically located in non-English speaking countries but recruit English-speaking teachers. The hiring process for international schools can be a high-stakes and risky proposition for both teachers and the administrators who recruit them. With limited information and time, administrators must assess whether a candidate is a good fit for the school. While administrators tend to focus on recruiting teachers who they believe will positively impact the student experience and help sustain the school culture (Gauthier and Merchant, 2016), they must also consider the costs associated with recruiting, securing visas, and moving the teacher to an international school. Thus, poor hiring decisions have not only educational implications, but also financial ones.

Teacher turnover

The decision to leave any job can be highly personal, carefully considered, and the result of multiple contributing factors and circumstances. Teacher turnover in national contexts has been widely explored, and Ingersoll’s (2001) work underscores the importance of organizational structures as an influence on teacher turnover in the United States. Ingersoll’s analysis provides important distinctions between two types of teacher turnover: attrition and migration. Teacher attrition refers to educators who leave the profession entirely and teacher migration identifies those who leave one teaching job for another. At the national level, these types of leaving are perhaps easier to track and report. While teacher retirement is a significant reason for teacher leaving in the broader research on turnover, our experiences at international schools suggest that retirement is seldom a reason for teacher leaving in the vastly different international school context. The literature on teacher turnover broadly reveals numerous factors that contribute to educators leaving their positions. These factors include salary (Changying, 2007; Buchanan, 2010; Akiba et al., 2012), working environment (Gilpin, 2011; Harris et al., 2019), personal factors (Borman and Dowling, 2008; Player et al., 2017; Smith and Ulvik, 2017; Trent, 2017), and other professional opportunities (Smith and Ulvik, 2017).

Teacher turnover at international schools

For international schools, teacher turnover is typically less easy to survey and document because of the multiple types of schools globally, and the absence of a centralized hiring structure. Data on teacher attrition and teacher migration at international schools are difficult to obtain for a global industry with few overarching or organizational attachments. International schools are typically private and independent institutions that may or may not be affiliated with an organization that connects them to similar schools in other locations or countries. It is difficult to assess teacher turnover systematically across independent institutions in disparate geographic locations.

Within the international school industry, 2-year teaching contracts are typical, and a number of factors have been found to influence teacher turnover or contract non-renewal. Hardman (2001) found that only 48 per cent of respondents in a study of 30 teachers at five international schools in four countries had renewed their two-year contracts. In a study of influential variables affecting teacher turnover at international schools, (Odland and Ruzicka, 2009) examined expatriate teacher leaving among 281 responses to a survey distributed to members of the Council of International Schools (CIS) database. Administrative leadership was identified as the most influential component in teacher decision-making, with three causal factors pertaining to administrative leadership supporting this finding. Three variables, (a) communication between senior management and faculty, (b) support from the principal and senior management, and (c) teacher involvement in decision making, emerged as the top factors for teachers in relation to leaving a school. These variables have been confirmed by more recent studies as well. International teacher recruitment and retention has been linked to factors such as location of the school (Chandler, 2010), school leadership (Hardman, 2001; Mancuso et al., 2011; Gomez, 2017), transparency during recruitment (Anderson, 2010), reasons and expectations for overseas teaching (Cox, 2012), finances and salary (Wong and Lucas, 2020), workload (Proctor, 2019), ties to home and host communities (Roskell, 2013; Johns, 2018), and opportunities for professional advancement (Gomez, 2017).

Breaking contract at international schools

While previous research reveals that factors such as organizational conditions, school characteristics, and teacher characteristics play a role in international teacher recruitment and retention (Odland and Ruzicka, 2009; Mancuso et al., 2011; Cox, 2012), breaking contract has not been a specific focus of studies thus far. Johns’ (2018) dissertation examined “premature leavers” from a single international school in Thailand, but we found no other work that investigated breaking contract in international schools. For teachers, the decision to accept an offer to work overseas involves risk. Adjusting to the professional demands of working in an unfamiliar curricular environment, moving to a new country, and integrating into a new culture bring additional complexities to the process of adjusting to a new job. Given the magnitude, and number of changes that international school teachers experience in their new job, it is not surprising that many individuals experience the various phases of culture shock when adjusting to their new situation (Roskell, 2013). The stress associated with culture shock can have a noticeable impact on their work and behaviors in daily life and schools (Halicioglu, 2015).

Most international teachers who get hired perform well, contribute positively to the school and complete, if not renew, their contracts (Odland and Ruzicka, 2009). However, some hiring decisions do not work out well, and in extreme cases, a dissatisfied teacher may break contract and leave the school mid-year. Online sites1 such as the International Schools Review Discussion Board and Reddit threads on breaking contract highlight how this is a phenomenon impacting schools and teachers alike. Magazine articles also highlight how breaking contract can result in economic losses, damage to professional reputation, or blacklisting from future employment fairs (Archer, 2017; Minthorn, 2017).

Breaking contract is an important phenomenon to explore particularly when teachers are difficult to recruit or replace. When we began researching this phenomenon in 2016, teacher oversupply in Canada meant that many newly graduated Canadian teachers unable to find work in their home country were deciding to begin their careers in overseas positions (Ingersoll, 2014). Teacher supply is cyclical, and at the time of our interviews, some jurisdictions in Canada were experiencing an oversupply of teachers while international schools were facing a recruitment crisis that continues (ISC Research, 2023). According to UNESCO (2023) there is a global teaching shortage, and international schools are increasingly finding it difficult to find qualified staff (Ingersoll et al., 2018). There are several factors influencing this international shortage, including rapid growth in the number of international schools (Brummit and Keeling, 2013) and global efforts to ensure universal access to education (Guardian, 2011). Further, there is evidence from human resources research that employees are reluctant to move to countries with poor reputations for safety and stability (Ceric and Crawford, 2016). Fear for personal safety is something we have heard informally from directors of recruitment fairs as being a factor in teachers’ decisions not to apply for jobs abroad, or to leave them, and has also been reported by others (Pennington, 2015).

Given the difficulty recruiting new teachers, it is becoming increasingly important for schools to retain the staff they recruit, as research from both international and public schools has long shown that high staff turnover brings substantial financial, cultural, and educational costs to the school (Hayden and Thompson, 1998; Milanowski and Odden, 2007). The financial consequences include the cost of recruitment, moving, induction, and visas. Depending on circumstances, these costs may be as high as $20,000 USD, although these costs may be reduced if the replacement teacher (often a local hire) is paid lower than the leaving teacher. Educationally, we know that high teacher turnover is associated with poorer achievement (Ronfeldt et al., 2013), although some researchers argue that having dissatisfied teachers leave the school brings an educational benefit (Feng and Sass, 2012). While we did not find literature that addressed the impact of staff turnover on school culture and reputation, we know that high staff turnover is associated with poor corporate reputations (Chun, 2005).

Research questions and methodology

As shown above, contract non-completion within this context has profound implications for a range of stakeholders including teachers, administrators, students, and parents. To better understand this phenomenon, this paper focuses on three specific questions:

1. What are typical reasons that teachers break contract?

2. What is the impact on the school when a teacher breaks contract?

3. How do international school administrators reduce contract non-completion?

This qualitative, exploratory study uses descriptive and inductive methods (Creswell, 1998; Bogdan and Biklen, 2003). Semi-structured interviews were used as the primary data collection tool.

The interview protocol was developed by the study authors, and reviewed by an independent qualitative researcher who has published research about international schools. After two rounds of quality checking, the final interview protocol was established. Semi-structured interviews provided the researchers with a consistent interview protocol while providing flexibility and space for participants to express what was important to their contexts. Because the researchers independently conducted interviews, the protocol established consistency and allowed for data collected by each researcher to be combined according to the research questions. Given the diverse range and nature of international schools (Hayden and Thompson, 1998, 2016) this approach allowed for participants to flexibly describe their context and experiences within the structure of the interview protocol and in alignment with the research questions.

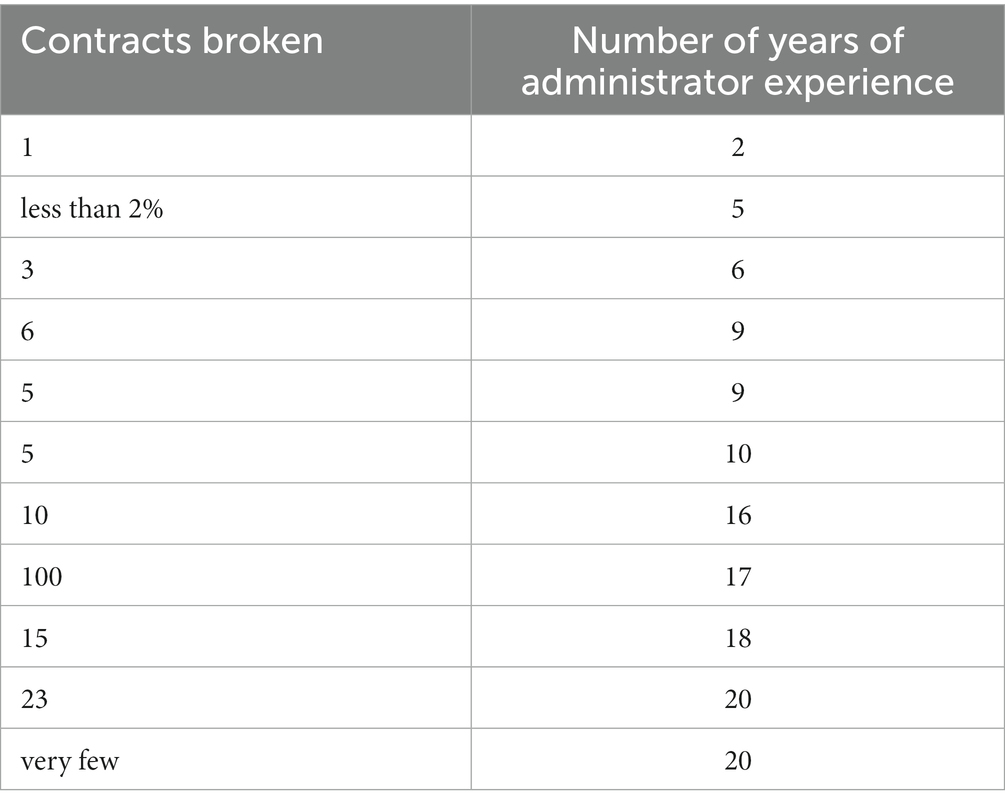

Research ethics board approval from the researchers’ institutions was obtained prior to participant recruitment. An email invitation to participate was sent to all administrators at one international school recruitment fair in North America. We interviewed 13 international school administrators in total, but because interviews 1, 2, and 6 were with administrator/human resource pairs from the same school, there were a total of 10 interviews conducted overall. Participants had varying durations of administrative experience in international schools—ranging from 2 to 20 years. Most of the 13 participants were administrators with an educational focus (e.g., 11 interviewees were principals or heads of school) and two interviewees were human resources specialists who participated in paired interviews alongside the school head/ principal. Using the typology of Hayden and Thompson (2016), we classified our participants as representing 6 Type A schools and 4 Type C schools. Type A schools cater to globally mobile expatriates while Type C schools cater mostly to local families. The organization that manages the recruitment fair is selective in which schools are admitted to the fair. Schools at this fair only hire certified teachers and have good reputations in terms of how teachers are treated. Twelve of the participants were interviewed while at the international teacher recruitment fair, and the thirteenth was interviewed via Skype. All participants were North American and, with the exception of one who worked in her home country, worked as expatriates outside their countries of origin.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, and then thematically coded using both inductive and deductive methods. An initial set of codes was developed based upon the findings of our literature review and own experiences working in international schools. These codes related to teachers’ personal qualities, dimensions of ‘fit’, hiring processes, administrator characteristics, and impacts on schools and teachers. After coding the first interview we added codes relating to supports for teachers and preventative measures to reduce contract non-completion. No further codes were added after this. As a quality check, the first transcript was coded independently by two of the authors. After coding, these two authors met to discuss inconsistencies in the coding. There were no direct disagreements in the coding, but there were instances where one author would code a portion of the transcript, and the other would not. After discussion and clarification so that the first transcript was coded identically, a second transcript was coded independently by each author, and a second round of quality checking took place. Again, there were no disagreements in codes, but there were some passages coded by one author and not the other. Consequently, the authors coded every transcript independently and then resolved inconsistencies through cross-checking and discussion.

Findings

Administrator experiences with breaking contract

In our recruitment email, we did not specify that participants must have directly experienced contract non-completion to engage in the study. Thus, we asked each participant “how many teachers do you know who have broken contract?” While prevalence of contract non-completion was not a focus of the study, we wanted to ensure that all participants had direct experience with contract non-completion. In our sample of administrators—all of whom worked at reputable, high paying schools in desirable locations, and were recruiting at a reputable hiring fair—each had experienced the phenomenon of contract breaking multiple times, but with varying frequency. Table 1 provides an overview of the administrators’ reports of the number of experiences with contract-non completion in relation to their number of years as school leaders.

At the extreme end, one administrator with 17 years’ experience reported dealing with over 100 broken contracts during his career. This exceptionally high number was likely because of his extensive recruiting work for a large group of schools. Another administrator described a year where many contracts were broken because of extreme dissatisfaction with decisions made by the previous administration. These examples were atypical, with most administrators reporting that broken contracts were not common and giving numerical answers of approximately one broken contract per year. Two participants did not provide numerical responses, but one indicated “very few.” The other stated that the prevalence of contract breaking was “less than 2 percent overall” although the rate was higher (10%) in the previous year, including “one who did not appear at all.”

Administrators reported that the number of broken contracts experienced during their careers could vary, depending on the school location, the salary offered, and the quality of hiring and induction practices. One administrator in Africa said that while in the past it typically happened once per year, or once every 2 years, “right now it’s more often.” Further, some administrators attributed this increase to a generational shift in attitudes, referring to “millennials” who are “very entitled.” Another administrator said about younger teachers, “if they are unhappy they move on and they do not really realize what, you know, it could jeopardize their careers.” Another administrator in Asia added that “in our experience, the younger people” are the ones who break contract, and this was because they lacked self-knowledge. This was not a universal view among our sample. When an administrator in Latin American was asked about the characteristics of teachers who break contract, they indicated a similar sense that it was more predominant among young teachers, but clarified that “I’d like to say young, but some of them have been older,” and then went on to say that teachers at all stages in their career may break contract. While prevalence varied across the body or responses, all participants confirmed that broken contracts are a reality that must be managed by international school administrators and the impacts can vary according to the category of non-completion.

Five categories of contract non-completion

While our research questions used the term breaking contract, our findings revealed that contract non-completion happens in multiple ways. Administrators in our study described the different ways that contracts might not be fulfilled but did not use legalistic terms like breach of contract. Across all the interviews, we counted five categories of contract non-completion given by administrators. These categories were consistent across our participants, although the terminology was sometimes different. We present the categories here using terminology that represents both employment terms and administrators’ descriptions of each category: reneging, no-shows, early leavers, runners, and termination.

For the first category, we use the term reneging, an employment term used when a person accepts a job offer (via email, phone, or signed contract) but later rejects the offer for another opportunity (Reger, 2021). The first category includes those who have signed a contract but change their mind, contact the school, and provide a reason for breaking contract before the start of the school year. Renegers are distinguished from the second category because they provide notice, unlike the second category—no-shows. No-shows sign a contract but never arrive at the school, and never give notice to the school. The third category is early leavers. Early leavers begin the job but leave before the end of the contract. This was by far the most common form of contract non-completion reported by our administrators. Early leavers give a range of reasons for not completing their contract, and give varying amounts of notice but, importantly, they give notice to the school of their intent to leave. Early leavers also work with the administration to make the leaving process as orderly as possible. This contrasts with runners, who form our fourth, and rarest category. Runners are teachers who have already accepted employment, moved to the country of the school, begun the position, and formed relationships, but who one day fail to show up for work and leave without notice or further contact. Only three of our administrators had direct experience with runners, and for two of these three, this was a form of contract non-completion they had experienced only once. Thus, while runners cause the most disruption to a school, they are also the rarest form of contract breakers. The final category of contract non-completion was termination by the school. This is distinct from the other four because it is the school ending the contract, and not the teacher. It should be noted that for most schools, this is not truly breaking contract because international schools typically have contractual language indicating that termination of the employment of teachers before the end of the term of the contract is permissible if the employer has sufficient grounds. Termination is, however, a form of contract non-completion.

Reasons for contract non-completion

The reasons for contract non-completion were varied across and within the five categories, and difficult to ascertain if the teacher did not give notice. The first category, reneging, can be divided into two subcategories that related to the reasons given for the not honoring the contract. The first sub-category gave the school notice they would not be starting their teaching, but either did not give a reason, or gave a reason that was not valid in the eyes of the administrator. One administrator recalled receiving an email shortly before the school year was to start where the teacher,

just wrote and said that she would not be coming after all. And it was pretty abrupt and also very—no explanation whatsoever. Nothing. Because we, you have to understand life happens and people may get sick or things may come up, but at least they should let you know what happened or what, you know, give you some idea.

The second sub-category had an acceptable rationale for reneging after signing a contract. One participant related a story were he “had a situation where a person, I mean, this was for a principal, you know, and she writes to me and says, ‘I never thought I’d be in this position, but things are falling apart back home with my mother’s health’.” While the late notice created difficulty for hiring a new principal, the administrator was understanding, saying, “It was a valid reason.”

The two most difficult contract non-completion categories for schools are no-shows and runners, and for these categories administrators were often not able to articulate reasons for teachers breaking contract, as the reasons were not communicated to the administrators. Two administrators (at the same school) reported finding out after the fact that one no-show had signed more than one contract and had opted to work at a different school. While this finding is not reported in other literature (that we are aware of) on international school leaving, the researchers have also had this experience. As teacher educators working with prospective international school teachers, we can confirm that teacher candidates have asked us whether they can “hedge their bets” and accept more than one contract to secure the best contract possible. Several administrators reported that a lack of communication was a good predictor of a teacher being a no-show. As an administrator from a school in Latin America told us, “I know they are not, they are not going to show up because they start not responding to my e-mails.”

No administrator was able to give specific reasons for runners not completing contract as these reasons were always unknown. One administrator described his experience with a seasoned teacher who left the school without notice during orientation, before the school year started. Even after more than a year of reflection, the administrator admitted not knowing why the teacher left, saying “I’m not really sure how, what triggered that response.” Administrators were sometimes able to give predictors of a teacher becoming a runner. Unhappiness with the climate, the food, or culture are important signs for a school leader to recognize. An administrator in South Asia thought that “unhappiness is one of the predictors. It’s, it’s one of the key predictors.” This was echoed by another administrator in East Asia who said he can tell someone will be a runner when there is “a lot of talking to other people about ‘we are not happy’.” More detail was provided by another administrator who said, “they are generally unhappy … you start to notice impatience. They seem to get upset over seemingly minor things.”

Another predictor was social isolation, or “not fitting in.” An administrator in Latin America said that runners “usually do not have a lot of friends,” and another administrator described a specific case beginning with “right from the beginning of orientation this guy is kind of a loner—he does not really gel with anybody.” Social isolation and happiness are likely to be related constructs. In talking about what it takes to thrive in an international school, most of our participants spoke of the importance of building community. The ability to foster positive relationships with their peers was ranked as equally important as teaching ability when administrators described the characteristics of a successful international teacher. One administrator put it bluntly, saying “If you cannot build relationships, it does not really matter to me how well you know your chemistry.”

While most administrators reported there were predictors of who would become a runner, there were two who felt otherwise. One of them described the decision to be a runner as “pretty instinctual” and added that “in some cases people just run.” Fit was also reported to be essential for success in an international school environment, and “when you are hiring a teacher, you know, you are hiring the whole of them and so in the class they can be gems, but outside the class they cannot function in society for whatever reason because they are not, they cannot fit into the culture.” Interestingly, no administrator mentioned burnout or stress (Roskell, 2013; Halicioglu, 2015) specifically, but extreme stress may explain why some teachers do not fulfill their contract obligations, despite the potential negative repercussions of such a decision. Not being a good fit for the school was not only reported as a reason for teacher leaving, but also for termination by the school. As a last resort, the teacher will be asked to leave, and one administrator reported “I’ve dismissed four teachers in the last 6 years mid-year because they were just toxic to the school and so if you count that as breaking contract, I broke the contract.” Administrators reported that interventions to support teachers who are unhappy are not always successful, and sometimes there is no other choice but for contract non-completion to occur in this manner.

The most prevalent category, early leaving, overlapped with the most frequently cited reason for leaving. Within our dataset the most common reason given for teachers breaking contract is changed family circumstances. This can range from having elderly parents at home who require care, to pregnancy, and a mother deciding that she wants her child born in her home country. In cases of changing family circumstances, all the administrators interviewed expressed the need to be empathetic toward the teacher, and to be as accommodating as possible. There was a strong sense that inflexibility in these situations did not serve the needs of any of the parties involved. It should be noted that one administrator believed that some teachers used family circumstances as an excuse, and that the true reason the teacher was breaking contract was unhappiness with their position. Unhappiness with their current position was the second most cited reason for breaking contract. This unhappiness could stem from missing friends and family back home, not being able to adapt to the host country culture, or not being able to adapt to the ethos and expectations of the school.

Impacts of contract non-completion

While high staff turnover is not ideal, the prevalence of two-year international school teaching contracts means teacher turnover is common within the industry, and hiring practices reflect this predictable cycle. What can be particularly disruptive for schools, however, is having teachers who break contract and leave the school before fulfilling their contractual obligations. Our participants reported that contract non-completion has many different impacts within the school and community. The impacts can be both short- and long-term, and often overlap. For schools, five key domains of impact were reported: (a) financial, (b) staffing (c) student learning, (d) school reputation, and (e) career implications for teachers. In this section we examine each of these dimensions from the perspectives of administrators.

Financial

The financial and human resource repercussions for the school are particularly acute when teachers leave after having begun their positions. Not only has the expense of recruiting the leaving teacher been for naught, but the costs associated with recruiting and bringing a new teacher on short notice can be very high. To mitigate the potential financial losses from teachers breaking contract, school administrators were keen to enact policies that encouraged contract completion, either through financial penalties or incentives. The most common policy, one reported by all schools represented in this sample, involved financial penalties for breaking contract. These penalties typically included repayment of flights and moving allowances. In terms of incentives, schools offered end of contract bonuses to teachers who completed their contracts. Bonuses ranged from 10 to 25% of the teacher’s annual salary. One Latin American school implemented a financial incentive for teachers to remain through an incremental reimbursement of the initial relocation allowance. Spreading the allowance over 3 months rather than providing an upfront lump sum was a financial mechanism meant to protect against loss from teachers leaving the school shortly after arriving.

For teachers who decide not to complete their contract, losing such incentives and others, including contract completion bonuses, relocation allowances, salary amounts, or rental deposits is a reality they must face. Teachers sometimes must make a choice between transparency and financial loss. For teachers who break contract by not returning to work after major holidays, or by making a call or sending a text message from the airport, these decisions about timing may be a way of mitigating some of the financial losses. One administrator shares how a recent early leaver who was transparent about her desire to break contract when she found it untenable to stay on:

[she] left in October and there were ramifications, financial ramifications, and she did it all above board. She did not just go to the airport and e-mail. That was just a situation where she probably underestimated what it was going to take to live and work here.

While financial penalties exist in most international school contracts, administrators indicated that repercussions for teachers can be difficult to enforce if teachers leave without any notice. One administrator noted that protecting those who are honest about breaking contract is important, “because otherwise they could have just gone to the airport and left us high and dry.” Another noted that there can be valid reasons for departure, and that honesty and integrity on the part of the teacher is an incentive for administrators to help teachers mitigate potential financial losses:

I’m a great one for honesty, again. So I am, I’m definitely going to work to help that person because again you leave me in a bind if you just run out… If I know it, I can start to plan. I can compensate for, for the next year and start to get ready. And I value having the integrity to come forward, and for some of them there are very valid reasons.

The financial losses for a school can range from $10,000 to $15,000 by one school leader’s estimation. This is consistent with our own personal experience as administrators in international schools, as well as with research conducted in public schools on the cost of teacher turnover (e.g., Milanowski and Odden, 2007; Watlington et al., 2010).

Staffing

Recruiting mid-year is extremely difficulty for international schools, as there are few teachers who are willing, and available, to move to an overseas teaching position in the middle of a school year. In the short term, administrators must scramble to make arrangements in contexts where ready solutions are not available. Unlike national public schools where there are typically supply or occasional teaching lists, international schools do not have a ready pool of qualified candidates to immediately replace a teacher who leaves. As result, other teachers may have to overload to compensate for the missing teacher. Three administrators talked about having to shift teaching loads across the school because of their inability to hire a subject-specific, qualified replacement for the parting teacher. In recalling a specific incident, an administrator in Europe recalled “there was quite a bit of shifting” and added “you rely upon the good will in an international environment on the staff that you have already got.” The additional workload for teachers who remain can initiate another set of impacts if a replacement teacher is not found quickly.

Student learning

The primary concern about the impact of contract non-completion, and the only impact reported by all participants, was the concern about how student learning is affected by the departure of a teacher during the school year. According to one administrator, when a teacher breaks contract “the ultimate losers are the kids.” Another administrator remarked that students with special learning needs were especially impacted because the teacher leaving knew “how the students have been learning throughout the school year till now and which students are with more needs, in what subject, and what has to be supported most.” Further, because changes to staffing had impacts across the school, a single teacher leaving could have negative learning impacts across many different classrooms. An administrator in Latin America noted that parents at her school deeply value the teachers, and the students tend “to fall in love with the teacher.” Thus, when a teacher leaves mid-year, it is a jarring personal experience for the students, and consequently for the parents. Administrators’ reports of the impact on student learning aligns with the findings of other research indicating lower achievement gains for students whose teachers left during the school year (Henry and Redding, 2020).

School reputation

When a teacher leaves, parents can question the reasons for the departure, and schools with high levels of turnover can gain a negative reputation on the international school circuit. Teacher leaving impacts the level of trust that parents have in the school, and the perception of school quality. Parents now need “to start having that confidence and trust that they went through at the beginning of the school year, but now with a different person.” Some of our administrators noted that it was a parental expectation their children would be taught by expatriate teachers—especially in the subject English. When an expatriate teacher leaves mid-year, they are typically replaced by a local teacher, as it is very difficult to find another expatriate teacher mid-year. Quality, as one administrator from Asia characterized it, is connected to payment for a native English speaker: “the parent feels they have paid this much money for this kind of program and you shortchange them on the English component of that program.” Another administrator from Latin America recalled a parent saying to her “I was very happy because my kid was going to learn like the native speaker, with a native speaker, even though the other teacher has very good English.” In contrast, we had two administrators report that parents were very supportive of the school, and consequently, a teacher leaving mid-year did not adversely impact the school’s reputation or perceptions of a quality education.

Career implications for teachers

The administrators we interviewed highlighted both short- and long-term impacts that contract non-completion can have for teachers’ careers. The impacts on leavers can vary depending on the reasons for breaking contract and manner in which they decide to leave, with administrators emphasizing a compassionate approach to contract release for teachers who were transparent about their reasons for leaving, particularly when faced with emergency situations back home. Administrators told us that leavers who communicated their intentions with professionalism were met with equal measures of professionalism and understanding. However, administrators were also clear that the long-term impacts of breaking contract in an unprofessional manner could include negative financial and career repercussions.

Administrators saw two negative consequences of breaking contract on a teacher’s future career. The first applied only to new teachers and related to missed experiences and curricular knowledge. Several administrators noted that for new teachers, a successfully completed contract would open doors to better opportunities. These opportunities ranged from contracts with other, better paying schools, to positions of responsibility and pay raises within the same school. The second consequence was teachers suffering a blow to their professional reputation. While all the administrators in our sample reported not wanting to cause undue harm to teachers’ reputation or future job opportunities, they also reported that teachers who break contract can be blacklisted. An administrator at an Asian school told us:

There are constantly e-mails coming out from [name of email list] saying if this person contacts you for a job make sure you contact me first. So those are almost exclusively people who have broken contract and left, like left schools in the lurch. So, from the minute they do that the school sends out an e-mail to the wider network. And this is hundreds of schools around the world who now have your name.

Another administrator from Latin America expressed the same idea more succinctly by saying “we all talk to each other.” Blacklisting a teacher appeared to be something administrators did with reluctance. One commented “you do not want to hurt someone’s chances for getting a job,” but when a teacher’s actions had harmed the school, administrators felt duty bound to their peers to report that action in an effort to prevent other schools from suffering the same fate.

Preventing contract non-completion

Beginning a new teaching job can be a challenging transition no matter where you start (Kutsyuruba et al., 2013; Olson, 2015; Mizzi and O’Brien-Klewchuk, 2016). In international school settings, however, transition challenges can be amplified by the requirements of adapting to a new host culture, geographical region, school culture, and social milieu. In this study, administrators reported that honest communication, logistical and personal supports, and a tiered approach to supporting teachers’ personal and social arrangements before focusing on the more formal academic and professional supports is necessary in international school contexts. Additionally, administrators offered suggestions for recognizing if a teacher is thinking of leaving the school.

Honest communication

Our participants emphasized the importance of being open and honest with potential hires about the school, its environment, and the challenges the new hire might face. This finding corresponds with Fong (2015) study of job satisfaction and contract-renewal among international school teachers in Asia. Out of 116 participants, Fong found differences between millennials and other generations when it comes to teacher retention, and communication was a significant factor in contract renewal for millenials.

An administrator in Latin America said that “being honest about the living situation, the hiring package” was important for preventing disappointment and disillusionment with new hires. The importance of frank, open communication about the school context was deemed especially important when hiring teachers who were female, not white, or not heterosexual. As an example, one administrator from the Middle East said that when hiring female teachers it was important to be “open about you are moving to a Muslim country, you know, this is what it’s like. Do not, do not sugar coat it… just be very open with them and honest.” Another administrator in Asia recalled a specific incident where his first choice of hires for two positions were a same-sex couple, and he needed to be frank about the prevalent attitudes toward same-sex relationships in the school’s host country.

When talking about the importance of open, honest communication, four participants recognized that some schools mislead potential hires about what the living and work conditions are like at the school. As one participant put it, “there are some unscrupulous people around who whatever lie to you and steal to try and get teachers to come work for them.” Administrators saw this practice not only as dishonest, but also as harmful to the school, as it would lead to higher rates of contract non-completion. An administrator in Asia said that schools create conditions that lead to contract non-completion when “the bill of goods that they sell…create a set of expectations that are not true.”

A similar perspective was offered by another administrator who said that if “the school is not fulfilling on their side of the contract” it provides teachers with “very legitimate reasons” for not completing the contract. An administrator from the Middle East put it even more forcefully saying “if the school misrepresents what was promised to you, ultimately you do not have any other choice but to break contract right?” Administrators also expected prospective teachers to not only be open and honest about themselves, but also to research the school and the country in order to self-assess whether they were a good fit for the position. One administrator recalled watching candidates at a job fair look at a map to see where a country was located after accepting a contract. This same administrator exhorted applicants to “do your research.” This was a sentiment expressed by all our participants. Another finding related to communication was administrators’ recommendation that teachers who are considering contract non-completion should bring their concerns forward. There was a consensus that good communication can lead to supports that might mitigate teacher leaving, or to pathways where teachers are able to be released immediately or in an expedited timeline from the pressures or difficulties their positions or situations entail. If teachers must break contract to return to their countries of origin to address unforeseen issues that arise once they are overseas, such as personal or family health issues, open communication around the factors that influence their decision to break contract can be discussed and supports can be implemented.

Logistical and personal supports

In national teaching contexts, administrators are not involved in teachers’ housing searches or personal lives in the same way that international contexts necessitate. In their work on pre-departure information for transnational teachers, Mizzi and O’Brien-Klewchuk (2016), p. 330 highlight the challenges that arise without such supports:

There was no orientation prior to our departure or manual to read or work through and, although support upon arrival was promised, the follow through was sparse. What seemed as an ‘orientation’ functioned more as a ‘disorientation’, as it was mostly centered on familiarizing ourselves with the curriculum, getting our bank accounts, and finding apartments (if that).

Across our administrator data, high levels of personal communication and logistical support were emphasized as necessary parts of teacher retention and contract renewal. These supports started before the teacher arrived at the school with actions such as securing visas and connecting new hires to teachers already at the school, so the new hire could ask questions about their upcoming position and orient to the community they would join. Further, administrators reported that either they, or someone in human resources, acted as counselors and confidants for their teachers once they had assumed their jobs. One administrator described this as “they know that they count on me twenty-four seven and they have my cellphone.” Another reported how she supported a teacher who wanted to leave early and immediately, encouraging the educator to take it “week by week” and providing nightly company and home-cooked meals to support them until the end of term. In international teaching contexts, the school often forms the core of a teacher’s community. Familial or community support networks are either absent or weak when compared to the teachers’ home communities, and additional, immediate, and intentionally constructed personal and social supports are necessary for successful transition to and teacher retention within international teaching. The next section provides an exemplar for supporting teacher transitions into an international setting.

Personal before pedagogical: tiered orientation and acculturation supports

One model of support that emerged as a form of protection against contract non-completion is a tiered system of orientation and acculturation that occurs over the course of 3 weeks. New staff are introduced gradually in tiers that address (a) familiarity with the local community & culture in week one (b) school orientation and continued introduction and interaction with local staff in week two, and (c) only in week three are new teachers and returning teachers brought together for a formal professional pre-service week. Within this gradual adaptation first to the community and the culture of the social environment, then to the school environment, and third to the formal professional and pedagogical expectations, this type of school orientation schedule mirrors the focal points for support reported by administrators in our study. Administrators consistently indicated that the personal necessarily precedes the pedagogical when it comes to finding the right person for an international school position, and that supporting personal development is essential to retaining teachers and fulfilling the pedagogical goals of the school. Tiered systems of orientation and acculturation were also correlated with administrators who reported low rates of contract non completion, and high levels of staff satisfaction.

Are they leaving? reading the signs

Being able to anticipate whether a teacher will fulfill their contractual obligations is not always possible, particularly in larger schools with many teachers, but there are certain indicators that could signal contract non-completion. Limited or reduced communication after a contract is signed was reported as a potential sign that a teacher might renege on a contract, for instance. While two of our participants felt they were not able to predict which teachers would break contract once on the job, the remaining participants reported that teachers who are likely to break contract often demonstrate similar characteristics and behaviors. Particularly in the case of those with two-year contracts, administrators identified a variety of signs that teachers may be considering leaving prior to completing their contracts. Most commonly, the strongest predictor of leaving was teachers’ unhappiness. Administrators shared that sometimes they “had a sense” that staff members were thinking of leaving and “could see the writing on the wall.” In other instances, there were no warning signs, or warning signs had not been noticed. Administrators reported four dimensions of unhappiness that could be read as signs a teacher may be considering breaking contract: (a) social withdrawal, (b) pedagogical/extra-curricular change, (c) selling or shipping home personal items, and (d) confiding unhappiness with select colleagues.

Of these four indicators, social withdrawal was reported as the strongest predictor. One administrator explained that he was worried that someone would break contract when they were a loner or “They change. They withdraw from some of the other people and become quiet and you do not hear something for awhile.” An administrator in Latin America noted that she gets worried when a new hire starts “becoming apart from everybody.” Alongside social withdrawal came withdrawal from work. An administrator from the Middle East said she could tell someone was likely to break contract by “a change in their daily demeanor and what they are doing even in the classroom. Because you’ll see them withdraw.” In another school it was noticed that two teachers had stopped coaching or supervising extracurricular activities. Interestingly, three administrators reported that teachers’ unhappiness in the host country did not translate to poorer classroom performance. A more obvious indicator that a contract was about to be broken was reported by two administrators who recalled specific events where teachers had been selling personal effects midway through the school year and shipping goods home. Finally, half of our administrators reported that when teachers are considering breaking contract “they usually talk about it with other foreign hires.” One participant related a story where he brought a teaching couple in to discuss their contract because he “kept hearing stuff” from their colleagues. While the teachers denied contemplating contract non-completion on numerous occasions, they had already shipped items home, and were intending on leaving without notice to avoid the ramifications of breaking contract. Recognizing the signs may offer administrators an opportunity to intervene with supports for teachers who are considering contract non-completion.

Implications, limitations, and conclusions

Although the administrators in our study reported that contract non-completion happens infrequently, there was some indication that it may be increasing, perhaps influenced by generational differences (Fong, 2015) and post-Covid (Bailey, 2021). We have received anecdotal reports that quarantines, lockdowns, and other disruptions caused a spike in contract non-completion at international schools. Our work offers unique insights into the prevalence of, reasons for, and impacts of breaking contract at international schools in the pre-Covid context. We connect our findings to the concept of fit, an idea that originated in a 2015 hiring study conducted with international school administrators by researchers (Gauthier and Merchant, 2015).2 Gauthier and Merchant provided the following definition of fit in relation to international school hiring:

fit is about who you are and who the school is. It is about mutual compatibility. It is the compatibility between teachers—including their values, beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, skills, and expectations—and the future schools in which teachers might work including their values as a school, their expectations, their mission, their location, their community, and their curriculum (Gauthier and Merchant, 2016).

Fit has also been taken up by Budrow and Tarc (2018), whose work connects the concept to specific capacities that teacher education can foster in a context of internationalization. Considering the global teaching shortage, attention to teachers’ capacities to fit into any local or global context will be of increasing importance for teacher education, international schools, and school administrators.

In categorizing the five types of contract non-completion, we offer researchers a typology for further studies on this phenomenon. We also acknowledge that while breaking contract has implications, not all of these are negative, and that changed personal circumstances can alter fit. Other more recent studies have shown how international teachers may be engaging in an elective precarity and enacting forms of leaving that are agentic (Bailey, 2021), so moving to another location or school may be a better fit.

As scholars exploring the arena of international school research, we have noticed from this study and others we have conducted in the field, that international school educators and administrators frequently exhibit willingness and reciprocity when it comes to participating in international school research. It strikes us that administrators’ positive responses to our limited recruitment notices may mean that not only are administrators eager to speak about their own experiences and contribute to the larger conversation, but they are also eager to learn from what others are saying about particular topics within international teaching. This willingness to participate in research, commit to an hour of interview time during an intense recruiting season, particularly during a busy recruiting fair weekend, suggests that international school administrators have a vested interest in speaking about their experiences with contract non-completion and teacher retention in international contexts, and eager to learn from others’ experiences. We hope that these results are reflective of the phenomenon in ways that can support new international school administrators looking for information on contract non-completion.

We also read this kind of engagement with research for practice as a potential dimension of a profile for international school leaders. As a conversation opener for each interview, we asked participants to tell us about what makes a successful international school teacher. Within the responses, they identified characteristics such as openness, willingness to participate in research, flexibility, creativity in the face of challenges, resourcefulness, problem solving skills, capacity to put the needs of the school above individual needs, willingness to serve as supportive mentors for new staff, leaders in creating a team culture, and positive ambassadors for international living and work. For international school administrators who wish to minimize instances of contract non-completion, a first step would be to assess for those qualities during the hiring process. Equally important, administrators need to be honest and transparent during the hiring process. Participants in our study expressed empathy and understanding for teachers who were hired by schools that did not represent themselves accurately during the hiring process and viewed contract non-completion as justifiable in those circumstances. Our participants also expressed empathy for teachers with changed or challenging personal situations that led to contract non-completion. There appeared to be an understanding that such circumstances were exceptional and that taking a hard line or being punitive toward the teacher was not going to change the teacher’s circumstance or decision. As former administrators ourselves, we commend administrators who strive for understanding and empathy first and see this is an important part of school leadership. Punishing teachers for breaking contract is intended to send a message to other teachers about the negative consequences of doing so, but treating teachers in a punitive manner can also send powerful messages and it is important that administrators consider how their actions affect the school climate.

In closing, we acknowledge that within the international school community, stories of “midnight runners” circulate freely, and many international educators know someone who simply did not show up for school one morning. However, our interviews with administrators revealed that breaking contract was normally an orderly and humane process, reached through consultation and discussion. It is worth restating that the administrators who participated in this research were from schools that had been previously vetted for recruitment at a reputable hiring fair. The lower rates of contract non-completion these administrators experienced could reflect the levels of support offered by their respective schools. While these administrators understood the costs associated with a teacher breaking contract, they also empathized with teachers who are unhappy in their positions and recognized that this unhappiness could foment poor morale at the school, and worked with teachers to support them in their contract non-completion.

Even with a small data set, we have captured some degree of the contextual complexity of leaving, and opened a conversation that we invite other researchers to enter. One important limitation of this study is that school administrators may be less likely to recognize their own role in contract non-completion. The factors reported by our participants tended to focus on candidate circumstances or characteristics, or on situations external to the school (e.g., the host country culture), although our participants’ discussion of problematic administrative practices and behaviors at other schools indicates that our participants were aware that school and administrative factors play a role in contract non-completion. Our next step is to report on the perceptions of teachers who have experiences with contract non-completion (Ingersoll & Merchant, in progress). Taken together, knowing both the experiences of teachers who break contract and the perceptions of administrators from schools that they leave behind can provide rich data for informing patterns and commonalities among teachers who break contract and the impact on the schools where they worked.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Queen’s University General Ethics Research Board and St. Thomas University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by a Harrison McCain Research Grant, awarded by the Senate Research Committee of St. Thomas University.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for Launa Gauthier and Elspeth Morgan’s early support of this work, and to David Phinney and Emily Fox for their research assistance.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^See https://internationalschoolsreviewdiscuss.wordpress.com/tag/breaking-an-overseas-teaching-contract/ andhttps://www.reddit.com/r/Internationalteachers/comments/m0so4a/fallout_from_breaking_contract/ for examples.

2. ^See https://earlycareerteachersdotcom.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/gauthier_launa_finding-fit-_internationalteaching.pdf and https://internationalschoolleadership.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Finding-the-Right-Fit-in-International-Teaching.pdf

References

Akiba, M., Chiu, Y. L., Shimizu, K., and Liang, G. (2012). Teacher salary and national achievement: a cross-national analysis of 30 countries. Int. J. Educ. Res. 53, 171–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2012.03.007

Anderson, J. S. (2010). The experiences of expatriate teachers 664 in international schools: five ethnographic case studies. Available at:https://login.proxy.hil.unb.ca/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.proxy.hil.unb.ca/dissertations-theses/experiences-expatriate-teachers-international/docview/892764845/se-2?accountid=14611

Archer, T., (2017). Breaking your contract in China: new consequences for pulling a midnight run. Available at: (https://www.echinacities.com/career-advice/Breaking-Your-Contract-in-China-New-Consequences-for-Pulling-a-Midnight-Run)].

Bailey, L. (2021). International school teachers: precarity during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Glob. Mobil. 9, 31–43. doi: 10.1108/JGM-06-2020-0039

Borman, G. D., and Dowling, N. M. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: a Meta-analytic and narrative review of the research. Rev. Educ. Res. 78, 367–409. doi: 10.3102/0034654308321455

Brummit, N., and Keeling, A. (2013). “Charting the growth of international schools” in International education and schools: moving beyond the first 40 years. ed. R. Pearce (London: Bloomsbury), 25–36.

Buchanan, J. (2010). May I be excused? Why teachers leave the profession. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 30, 199–211. doi: 10.1080/02188791003721952

Budrow, J. S., and Tarc, P. (2018). What teacher capacities do International school recruiters look for? Can. J. Educ. 41, 860–889.

Ceric, A., and Crawford, H. J. (2016). Attracting SIEs: influence of SIE motivation on their location and employer decisions. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 26, 136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.10.001

Chandler, J. (2010). The role of location in the recruitment and retention of teachers in international schools. J. Res. Inter. Edu. 9, 214–226. doi: 10.1177/1475240910383917

Changying, W. (2007). Analysis of teacher attrition. Chin. Educ. Soc. 40, 6–10. doi: 10.2753/CED1061-1932400501

Chun, R. (2005). Corporate reputation: meaning and measurement. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 7, 91–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00109.x

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry in research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage Publications. New York

Feng, L., and Sass, T. R. (2012). Teacher quality and teacher mobility (Andrew young school of policy studies research paper series 12–08). Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2020373&rec=1&srcabs=902032&alg=7&pos=8

Fong, H. W. B. (2015). Job satisfaction and dissatisfaction factors influencing contract renewal of generation y and non-generation y teachers working at international schools in Asia. Liberty University. Lynchburg

Gauthier, L., and Merchant, S. (2015). Why take the risk? Factors that influence international schools to hire newly qualified teachers. Queen’s University, ON, Canada

Gauthier, L., and Merchant, S. (2016). Hiring newly certified teachers: what’s in it for international schools? J. Assoc. Adv. Int. Edu. 42, 106–107.

Gilpin, G. A. (2011). Reevaluating the effect of non-teaching wages on teacher attrition. Econ. Educ. Rev. 30, 598–616. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.03.003

Gomez, F. M. (2017). Examining factors which influence expatriate educator turnover in international schools abroad (dissertation). University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, Ann Arbor.

Guardian, (2011) Global teacher shortage threatens progress on education. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/datablog/2011/oct/07/un-estimateteachers-shortageworldwide#:~:text=%22An%20acute%20shortage%20of%20primary

Halicioglu, M. L. (2015). Challenges facing teachers new to working in schools overseas. J. Res. Int. Educ. 14, 242–257. doi: 10.1177/1475240915611508

Hardman, J. (2001). “Improving recruitment and retention of quality of overseas teachers” in Managing international schools. eds. M. Shaw and S. Blandford (New York: Routledge-Falmer), 123–135.

Harris, S. P., Davies, R. S., Christensen, S. S., Hanks, J., and Bowles, B. (2019). Teacher attrition: differences in stakeholder perceptions of teacher work conditions. Edu. Sci. 9:300. doi: 10.3390/educsci9040300

Hayden, M. C., and Thompson, J. J. (1998). International education: perceptions of teachers in international schools. Int. Rev. Educ. 44, 549–568. doi: 10.1023/A:1003493216493

Hayden, M., and Thompson, J. (2016). International schools: current issues and future prospects. Edu. Rev. 69, 1–2. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2016.1237156

Henry, G. T., and Redding, C. (2020). The consequences of leaving school early: the effects of within-year and end-of-year teacher turnover. Educ. Finance Policy 15, 332–356. doi: 10.1162/edfp_a_00274

Ingersoll, R. M. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: an organizational analysis. Am. Educ. Res. J. 38, 499–534. doi: 10.3102/00028312038003499

Ingersoll, M. L. (2014). Leaving home, teaching abroad, coming home: a narrative journey of international teaching. Queen's University. Canada

Ingersoll, M., Hirschkorn, M., Landine, J., and Sears, A. (2018). Recruiting international educators in a global teacher shortage: research for practice. Int. Sch. J. 37, 92–102.

ISC Research (2023). Recruitment challenges hit international schools. Available at: https://iscresearch.com/recruitment-challenges-hit-international-schools/

Johns, E. M. (2018). The voices of teacher attrition: perceptions of retention and turnover at an International school in Thailand. University of California. California

Kutsyuruba, B., Covell, L., and Godden, L. (2013). Early-career teacher attrition and retention: a pan-Canadian document analysis study of teacher induction and mentorship programs. Kingston, ON: Queen's University

Mancuso, S. V., Roberts, L., and White, G. P. (2011). Teacher retention in international schools: the key role of school leadership. J. Res. Int. Educ. 9, 306–323. doi: 10.1177/1475240910388928

Milanowski, A. T., and Odden, A. R. (2007). A new approach to the cost of teacher turnover. Seattle, WA: School Finance Redesign Project, Center on Reinventing Public Education

Minthorn, J. (2017). How to get a job teaching at an international school. Available at: https://www.vergemagazine.com/work-abroad/articles/2047-how-to-get-a-job-teaching-at-an-international-school.html

Mizzi, R. C., and O’Brien-Klewchuk, A. (2016). Preparing the transnational teacher: a textual analysis of pre-departure orientation manuals for teaching overseas. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 19, 329–344. doi: 10.1080/13678868.2016.1203637

Odland, G., and Ruzicka, M. (2009). An investigation into teacher turnover in international schools. J. Res. Int. Educ. 8, 5–29. doi: 10.1177/1475240908100679

Olson, J. S. (2015). “No one really knows what it is that I need”: learning a new job at a small private college. J. Contin. High. Educ. 63, 141–151. doi: 10.1080/07377363.2015.1085947

Pennington, R. (2015). Teachers from overseas are harder to find. Available at: https://www.thenationalnews.com/uae/education/teachers-from-overseas-are-harder-to-find-1.131491

Player, D., Youngs, P., Perrone, F., and Grogan, E. (2017). How principal leadership and person-job fit are associated with teacher mobility and attrition. Teach. Teacher Edu. 67, 330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.017

Proctor, K. N. (2019). Wellness paradigms in predicting stress and burnout among beginning expatriate teachers. Available at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/7834

Reger, A. (2021). The risks of reneging hire Lehigh: the center for career & professional development. Available at: https://www.hirelehigh.com/post/the-risks-of-reneging

Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., and Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 50, 4–36. doi: 10.3102/0002831212463813

Roskell, D. (2013). Cross-cultural transition: international teachers’ experience of ‘culture shock’. J. Res. Int. Educ. 12, 155–172. doi: 10.1177/1475240913497297

Smith, K., and Ulvik, M. (2017). Leaving teaching: lack of resilience or sign of agency? Teach. Teach. 23, 928–945. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2017.1358706

Trent, J. (2017). Discourse, agency and teacher attrition: exploring stories to leave by amongst former early career English language teachers in Hong Kong. Res. Papers Edu. 32, 84–105. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2016.1144215

UNESCO. (2023). World teachers’ day: UNESCO sounds the alarm on the global teacher shortage crisis. Available at: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/world-teachers-day-unesco-sounds-alarm-global-teacher-shortage-

Watlington, E., Shockley, R., Guglielmino, P., and Felsher, R. (2010). The High Cost of Leaving: An Analysis of the Cost of Teacher Turnover. J Edu. Fin. 36, 22–37. doi: 10.1353/jef.0.0028

Keywords: international schools, teacher turnover, teacher recruitment, breaking contract, teacher retention, teacher leaving

Citation: Merchant S and Ingersoll M (2024) Administrators’ perspectives on teachers breaking contract at international schools. Front. Educ. 8:1248229. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1248229

Edited by:

Angeliki Lazaridou, University of Thessaly, GreeceReviewed by:

Adam Poole, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, ChinaAntonios Kafa, Open University of Cyprus, Cyprus

Copyright © 2024 Merchant and Ingersoll. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Marcea Ingersoll, marcea@stu.ca

‡ORCID: Marcea Ingersoll, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8704-4863

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Stefan Merchant

Stefan Merchant Marcea Ingersoll

Marcea Ingersoll