One Foot in the Past: Compositions based on the dialects ofNewfoundland

One Foot in the Past:

Compositions based on the dialects of Newfoundland

Introduction

Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, is home of “perhaps the greatest regional diversity [of spoken English] to be found anywhere in North America” (The Dialect Atlas of Newfoundland and Labrador. N.D.). But like dialects worldwide, the regionally distinct speech patterns of the province are in a state of decline, as mass media and easier travel have removed the isolation that caused them to develop in the first place. As native Newfoundlanders, we are proud of our rich dialectal heritage. We sought to celebrate it with a large-scale musical tribute while it is still a living reality. The result is One Foot in the Past (Centrediscs, to be released 2023), a 65-minute album weaving together Newfoundland speech and traditional folk music with contemporary techniques of speech-based, timbre-based, and textural composition. A project eight years in the works, this album also draws on scholarly research in music perception, dialectology, timbre phonetics, and several types of sound analysis and synthesis. This module details the backgrounds and influences, methods, and results of our tribute to the dialects of our home province.

1. Background and Influences

The research component of the project involved studying (1.1.) contemporary trends in speech-based music, (1.2.) archival sources of Newfoundland folk music, (1.3.) guitar timbres and their acoustical relations to speech sounds, and (1.4.) the dialect families of Newfoundland. On the basis of these studies, we developed novel approaches to speech-based music for guitar, recorded speech, and electronics. We applied these approaches in the creation of the album, and are further evaluating their effectiveness through an ongoing perceptual experiment that will be the subject of future publications.

1.1. Speech-based music

Speech and the human voice have long been recognized as important models for instrumental music. In recent decades, aided by sound technology, a host of new approaches for integrating speech and music have emerged. Here we mention some examples that were particularly influential for our project; for a longer, more general discussion, see “The career of metaphor hypothesis and vocality in contemporary music” (Noble, 2022).

1.1.1. Melodic transcription

Many instruments can convincingly imitate the pitches and phrases of speech, and this technique has been used to great effect. A famous example is Steve Reich’s Different Trains (1988; Kronos Quartet recording), in which the instruments of the string quartet play melodic fragments that imitate speech clips in the tape track. In this case, the presence of the original speech recordings makes the analogy explicit, but a strong impression of speech-like quality can be conveyed through melodic imitation even when the original speech is absent.

1.1.2. Rhythmic transcription

Impressive musical imitation of speech can be achieved through rhythm alone, even when the pitch dimension is neutralized. Irish drummer David Dockery has published a series of YouTube videos in which he uses the drum kit to imitate speeches from TV shows and movies, such as Pepe Silvia (2017). This is a fun example of the recent trend of speech-based music reaching beyond the contemporary classical world into popular culture. Dockery’s performances are figured out by ear and not notated (according to his comments on this YouTube video, he loops speech fragments and thinks of the best way to phrase them a bit at a time), but some composers have produced scores for rhythmic speech-based pieces. For example, Andy Akiho’s Stop Speaking (2011; Martin Daigle recording) for solo snare drum and digital playback plays on synchrony and asynchrony between drumming and synthetic speech.

1.1.3. Spectral transcription

Computer analysis of sound signals can open new possibilities for speech transcription: not only the fundamental frequencies (pitches) but all of the component frequencies (spectra) can be tracked. Some composers have used spectral analyses to create speech transcriptions in which instruments reproduce several partials or formants in addition to the fundamental, imitating more of the original sound in the instrumental realization. This approach has been adopted by composers including Rolf Wallin in his string quartet Concerning King (2006; see Figure 2) ) and Jonathan Harvey in his orchestral piece Speakings (2007/2008; BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra recording). Peter Ablinger achieved impressively veridical spectral transcriptions in his “talking piano” pieces such as Deus Cantando (2009) in which a piano is played by a custom-designed robotic mechanism.

1.1.4. Dialect-based music

Relatively few pieces of speech-based music of which we are aware have specifically focused on dialects (regionally distinct speech patterns) as sources of musical interest. Two exceptions have been especially important examples for our work.

Trevor Wishart’s 2011 acousmatic album Encounters in the Republic of Heaven (subtitled “all the colours of speech”) uses as its source material interviews with residents of north-eastern England. While, according to the composer (personal correspondence), there was no explicit sociological, linguistic, or political agenda behind Encounters, this large-scale piece functions as a showcase for a series of striking dialects from the region, transformed and extrapolated into an amazing variety of musical textures.

An essential Canadian example of dialect-based music is René Lussier’s Le trésor de la langue (1989), an album that uses various instruments—most prominently the electric guitar—to imitate the melodies of recorded speech. Most of the recordings are from residents of Québec, and the importance of the French language is a focal theme. The musical result, a unique kind of experimental jazz fusion, is captivating. It is also extremely different from both Wishart’s sonic art and from our folk-infused approach, standing testament to the versatility of speech-based music.

1.2. Newfoundland folk music

The folk music traditions in Newfoundland and Labrador are a vibrant cornerstone of the province’s cultural life. We integrated these traditions both stylistically and thematically into the compositions on the album.

1.2.1. Vocal music

Many Newfoundland folk songs are well-known to residents of the province and are performed frequently by local professional and amateur musicians in pubs, concerts, and the province’s famous kitchen parties and shed parties. Having grown up in this tradition, we had been inspired by local folk singers such as Fergus O’Byrne and Pamela Morgan. We knew dozens of popular folk songs, but for this project we sought to find songs that were new to us and (hopefully) to the people we would interview on our tour (see 2.1.).

We consulted the archival Folksongs of Atlantic Canada: From the collections of MacEdward Leach, hosted by Memorial University of Newfoundland’s Folklore and Language Archive. MacEdward Leach was a folklorist who collected nearly 700 songs in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia between 1949 and 1951. The archive contains field recordings and transcribed lyrics for these songs. We reviewed the archive in search of songs that were collected in Newfoundland, that we judged to be relatively obscure based on our knowledge of the folksong tradition, and that addressed themes which we felt would be meaningful to Newfoundlanders today and would therefore be likely to get them talking.

1.2.2. Instrumental music

Instruments such as the fiddle, accordion, guitar, and found or improvised percussion instruments and folk genres such as jigs, reels, and square dances are also integral parts of the musical culture of the province. Although our primary focus in this album is on the voice, we drew on Newfoundland’s instrumental traditions as well, both as subjects of discussion and as stylistic influences in some of our pieces. We drew particular inspiration from famous Newfoundland folk fiddlers Rufus Guinchard and Emile Benoit, and from examples of instrumental music that people described or demonstrated for us during our interviews.

1.3. Timbre phonetics

In Music, Language, and the Brain (2008), Ani Patel writes that “there is no question that the primary dimension for organized sound contrasts in language is timbre” (p.50). Using timbre as a compositional parameter therefore holds great potential for speech-based music, opening the door to compelling relations between speech and music that extend beyond what is possible with melodic or rhythmic transcription alone. Some composers have manipulated timbre in speech-based music through ensemble or polyphonic textures or through electroacoustic procedures. The classical guitar offers additional possibilities in a solo, monophonic context. The instrument presents a tremendous palette of timbral variation, and as acoustician Caroline Traube has documented (2004), the differences between those timbres can be understood and perceived as analogous to differences between spoken vowels. We call the study of analogies between musical sounds and speech sounds timbre phonetics.

1.3.1. Timbral variation on the guitar

For all string instruments, the position at which a string is excited (for example, by plucking or bowing) affects the resulting timbre. This is why many string composers specify the excitation position with indications like sul ponticello (SP; close to the bridge, which accentuates the higher harmonics for a brighter sound), sul tasto (ST; over the fingerboard, which attenuates the higher harmonics for a duller sound), and ordinario (ord; ordinary position between the bridge and the fingerboard, which produces the normative timbre of the instrument). The differences in the spectra of guitar tones produced with these different pluck positions are readily visible in the following spectrographs:

1.3.2. Formant structures

Formants are regions of concentrated energy in a sound’s spectrum which are strong factors in timbre perception. Many discussions of formants focus on vowels because formants serve a primary role in distinguishing them. The following spectrographs show the differences in sound energy distribution between three common vowels: i (as in “ping”), a (as in “ha”), and u (as in “who”):

The formants of vowels appear as nodes in characteristic regions of the frequency spectrum.

1.3.3. Guitar-vowel analogies

Because guitar timbres and vowels have characteristic energy distributions in similar regions of the sound spectrum, effective analogies may be perceived between them. In general, nasal vowels (e.g., i) map onto SP positions, open vowels (e.g., o) map onto ord positions, and closed vowels (e.g., u) map onto ST positions. More precise discrimination of pluck positions (for example, in centimeters from the bridge) can move beyond these three broad categories to open up a substantial palette of vowel colours on the guitar (see 3.4.).

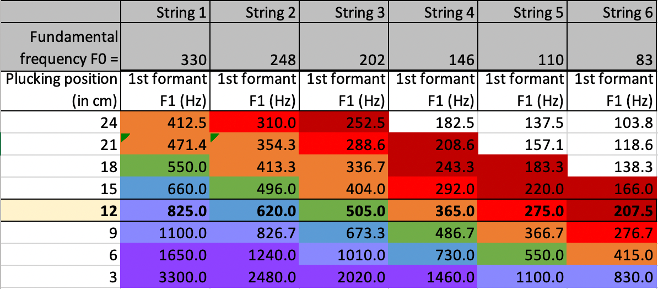

In diagram 5(a), the approximate frequencies of characteristic formants are listed in the left column, the corresponding vowels are listed in the colour-coded middle column, and example words are provided in the right column. In diagram 5(b), the plucking positions are listed in centimeters from the bridge in the leftmost column, and the corresponding formant frequencies for each string are listed in the subsequent columns. The same colour coding is used to demonstrate which pluck positions for which strings correspond with which vowels.

Figure 5: (a) Characteristic formant frequencies for seven vowels, and (b) Characteristic formant frequencies of the six strings of the guitar at various pluck positions. Colour coding between (a) and (b) indicates which vowels correspond with which strings and pluck positions. Diagrams prepared by Caroline Traube.

Phonetic analogies are important in guitar pedagogy and performance practice, with many guitarists and guitar teachers using spoken vowels as models for different tone colours. In this project, we employed them compositionally as well, notating tone colour changes in the scores as an additional way to imitate speech patterns with music for the classical guitar. The list of vowels represented in the above table is obviously far from complete: there are many vowels common in English and other languages that do not appear in this list, including many that appear in the dialects of Newfoundland. As such, a simple one-to-one mapping from the vowels of speech to the timbres of the guitar was not possible. We had to learn which vowels were important in the dialects that we sought to emulate, and which of the available timbres on the guitar would make for convincing analogies with them.

1.4. Dialects of Newfoundland

Dialects may differ considerably in their phonetic realizations of the same words: for any given written word on the page, different dialects may produce remarkably different sound patterns. As Sandra Clarke says in Dialects of English: Newfoundland and Labrador English (2010), “the pronunciation of vowels may differ markedly from one English variety to another” (p.23), so that “actual phonetic realisations may differ considerably” between dialects (p.26). Therefore, composing speech-based music that seeks to faithfully represent dialects requires careful attention to how vowels sound in different dialects, which may or may not correspond with how they look on the page.

The speech patterns of Newfoundland are incredibly varied, displaying “one of the greatest ranges of internal variation in pronunciation and grammar of any global variety of English” (Clarke 2010, 1). The differences between regions, communities, and individual speakers are so rich that no project of this nature could possibly represent the full dialectal palette of Newfoundland in all its glory. We needed to be selective while covering a broad sample, which meant learning more about how the dialects are grouped.

After consulting with linguists and folklorists at Memorial University of Newfoundland, we learned that a great deal of the dialectal variety in the province comes down to settlement history: for example, areas settled by the Irish hundreds of years ago continue to display strong affinities to Irish dialects today. By far the largest influences in settlement terms come from the historical speech patterns of Ireland and the Southern British Isles. Clarke lists three principal categories: Standard Newfoundland and Labrador English (S-NLE), characterized as “the standard, Canadian-like speech of many younger, urban middle-class residents of the province” (p.1); Newfoundland and Labrador Irish English (I-NLE), which refers to “everyday varieties spoken in areas of the province settled by the southeast Irish” (p.16), and Newfoundland and Labrador British English (B-NLE) which refers to “comparable varieties of southwest English origin” (pp.16-17). These categories are used to differentiate phonetic realizations between dialects, as in the following table which uses symbols of the International Phonetic Alphabet to show how vowels are realized differently between them:

The categories gave us a good starting point for understanding the dialect families of the province. But it would be oversimplistic to assume that dialects within a given category are interchangeable, as this would ignore the considerable regional variation between them. Also, there are smaller pockets of Scottish and French influences not represented in these categories.

A more detailed, community-specific breakdown is provided by The Dialect Atlas of Newfoundland and Labrador (Memorial University of Newfoundland), an online resource that provides linguistic analyses of particular features of grammar, pronunciation, and word choices for hundreds of communities in the province. Reviewing it helped us form a picture of where to go in the province to encounter contrasting examples of S-NLE, I-NLE, and B-NLE, as well as a few scattered examples of Scottish- and French-influenced speech patterns. The next step was to visit these places and interview people to record examples of their dialects.

2. Source material collection

2.1. Tour of Newfoundland

We visited communities including Cape St. Mary’s, Branch, Shearstown, Freshwater (Conception Bay North), King’s Point, Fogo, Tilting, Port-au-Port East, Cape St. George, and Port aux Basques, communities chosen to represent the major dialect families and also to cover a broad geographical spread of the island. We recruited sixteen willing participants for our interviews through coverage in local media and personal outreach. These interviews took place in people’s homes or in local establishments and were recorded with a Zoom H4n Handy Recorder. Our goal was to keep the tone of these interviews as comfortable, friendly, and informal as possible, in order to encourage people to speak naturally and freely. We planned the interviews to consist of recitations (2.1.1.) and semi-structured conversations (2.1.2.). An unplanned feature of the interviews was spontaneous musical performances (2.1.3.) that some participants voluntarily produced.

2.1.1. Recitations

So that we could directly compare dialects, we wanted to have some examples of different people from different communities saying the same words. To this end, we selected four folksongs from the MacEdward Leach archive (see 1.2.1.), printed the words to selected verses, and asked our interviewees to read them aloud. We deliberately sought songs that we thought people would not recognize, in order to avoid rehearsed performances. The four songs we selected were:

·2.1.1.1. Butter and Cheese, an example of a comical “tall tale.”

2.1.1.2. Kelly and the Ghost, an example of a ghost story.

2.1.1.3. The River Driver, which addresses yearning for home.

2.1.1.4. The Shabby Genteel, which addresses making the most of what you have.

2.1.2. Semi-structured conversations

After participants had recited the verses, we asked them to tell us what they thought the songs were about and then asked some follow-up questions. We also asked questions about other topics of interest such as the roles of dialects and music in community identity. The conversations, which we had anticipated would last about 20 minutes each, took on lives of their own and in many cases lasted longer than an hour. In the end we had about 18 hours of material, touching on many different aspects of life in Newfoundland today. Although our initial focus had been on the phonetic differences between dialects, it quickly became apparent that the stories our interviewees so generously shared with us were equally fascinating and a very meaningful source of inspiration. This prompted us to expand our compositional focus to include the themes and stories that emerged from our interviews, as well as the beautiful sounds of the dialects themselves.

2.1.3. Spontaneous musical performances

In addition to reciting the folksong lyrics and answering our questions, and much to our surprise and delight, some participants spontaneously sang or performed instrumental music for us. Many of the songs they performed were new to us, and some of them touched on themes similar to the ones we had emphasized in the interviews. These musical offerings became another rich source of material on which we could draw in our compositions.

2.2. Québec

We are both expat Newfoundlanders currently living in Québec, a province famous for defending its language and dialects. Indeed, the pride the Québecois feel for their language, powerfully expressed in Lussier’s Le trésor de la langue (see 1.1.4.), was one of the inspirations for our project. We sought to incorporate some French speech from Québec into the album, both to tap into its inherent beauty and to show links between the two provinces in the pride they feel in their own cultures and identities.

2.2.1. Planned interviews

Our original plan had been to conduct interviews in French with residents of Québec, to parallel our Newfoundland tour. Unfortunately, this plan was quashed by the COVID-19 pandemic. We would have needed to collect the interviews in 2020-2021, when lockdown measures made it impossible to visit people in their homes as we had done in Newfoundland. We considered conducting interviews on Zoom but the combination of the in authentic interview setting and the difficulty of capturing quality audio led us to seek other options instead.

2.2.2. Projet floral database

Fortunately, we found an open-source public database of speech samples from French-speaking regions around the world, including Québec: Projet floral, Phonologie de Français Contemporain. The interviews on this database cover a wide range of subjects. After perusing several hours of them, we found clips from speakers in Laval and Trois Rivières that presented interesting dialectal variety and touched on some of the themes we wished to address.

3. Technical methods

Having collected a large volume of source material, and after hundreds of hours reviewing and cataloguing it thematically, the next step was to “musicalize” the recorded speech in compositions. This process can take many forms, and we explored a variety of them in this project. We have already published and presented on our methods in several formats, including a lecture-recital in McGill’s Research Alive series, a paper in the peer-reviewed journal of the Guitar Foundation of America Soundboard Scholar, and Cowan’s doctoral dissertation. In this module, we go into more detail about the issues we encountered in implementing the various techniques in the pieces on the album, including (3.1.) melodic transcription, (3.2.) rhythmic transcription, (3.3.) harmonic transcription, (3.4.) timbral transcription, and (3.5.) electronic processes.

3.1. Melodic transcription

The idea of writing down the pitches of speech may seem straightforward, but in the process of doing it, we quickly discovered that it is not a simple matter of speech in –> melody out. For one thing, musical notes (at least in the tradition of Western standard musical notation) are characterized by discrete pitches and time intervals: for example, a quarter-note G sustains the pitch G for the full duration of the quarter note. This is rarely the case for the pitches of speech: rather than sustaining equal-tempered pitches for discrete note durations, speech melodies may fluctuate freely and microtonally both within and between syllables. Nevertheless, it would also be an oversimplification to characterize our perception of speech as a continuous glissando: we often do hear syllables as having defined pitches akin to musical notes, and we can hear spoken phrases similarly to musical melodies, as abundantly demonstrated in the speech-to-song illusion discovered by Diana Deutsch. So speech melodies appear to have some properties of continuous glissandi and some properties of discrete musical notes, and the transcriber-composer must make many judgments to decide how to effectively select and convey musical information derived from speech.

Sound analysis software such as Sonic Visualizer can aid in this process by providing a precise analysis of the fundamental frequency of the speech clip, as in the following example:

In some cases, it is obvious from the computer analysis what the pitch of a syllable is, but in the many more ambiguous cases, how one should decide what pitch to assign a syllable is unclear. A series of questions that extend beyond the information presented in the digital sound analysis come into play: most importantly, how do I hear these pitches? What is heard in the sound and what is seen in the analysis can sometimes deviate to a surprising extent. Should priority be given to the pitch at the onset of the syllable, or to the average pitch over time of the syllable as a whole? If a single syllable slides between more than one relatively stable pitch or encompasses a wide pitch interval, is it better to keep it as one musical note (to reflect its linguistic function) or to divide it into more than one note (to reflect its musical properties)? What interpretation provides for the most pleasing musical result? What interpretation will be the most playable for the performer? If the speech pitches deviate from equal temperament, is it better to try to achieve microtonal tuning for the sake of accuracy, or to approximate to equal temperament for the sake of expedience? All of these questions are context dependent. In the course of transcribing the melodies on this album, we were constantly rebalancing the equation to suit various contexts of speech, music, and perception.

To demonstrate the multiplicity of possibilities, here are three different transcriptions of the speech clip represented in the spectrograph above, with pitches prioritizing: (a) the onsets of syllables, (b) the average pitch over time of syllables, (c) an implied tonality. Note that none of these transcriptions is “correct”: they are all approximations simply in virtue of the fact that they have normalized the fluctuating pitch of speech to the static pitch representation of standard musical notation. Which one is chosen depends on the contexts and values described above. Note also that all of these transcriptions are in equal temperament: other solutions involving microtonal accidentals and pitch bends would multiply the possibilities even more.

3.2. Rhythmic transcription

Notating the rhythms of speech is perhaps even more complicated than notating its pitches, because in addition to deciphering the relative durations of syllables and phonemes, the transcriber-composer must be sensitive to relative accents between syllables and reflect them in the notation, whether by added articulations or by metrical implications. Some rhythmic transcriptions on this album are percussive, using sounds produced by striking various parts of the guitar with various parts of the hand (for a detailed description of the notation of these percussive effects, see Noble and Cowan, 2020). Others are melodic or chordal.

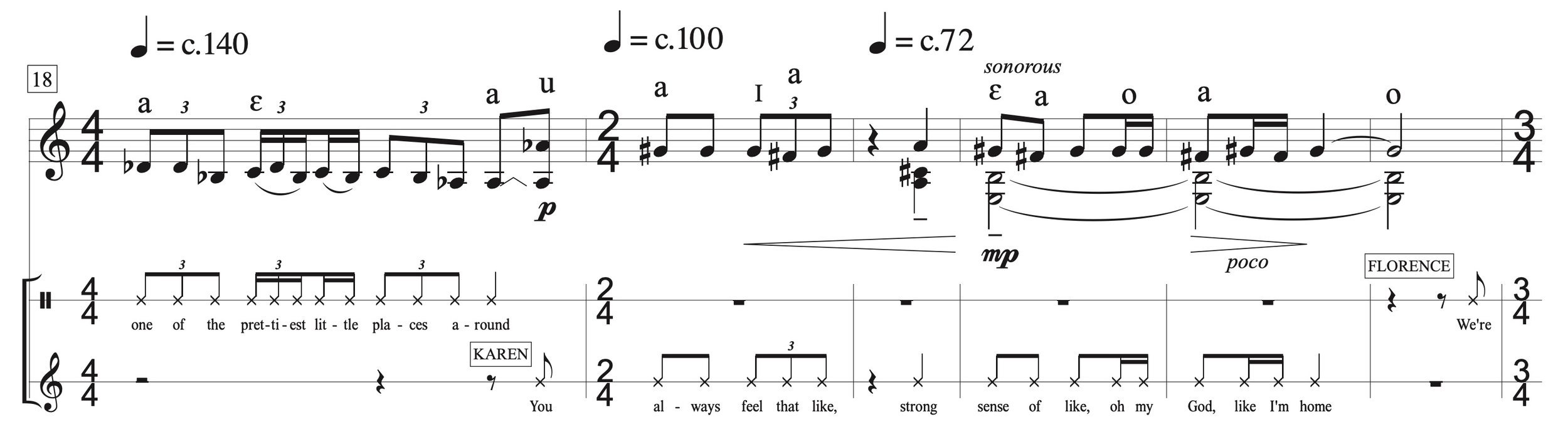

In preparing our rhythmic transcriptions, we felt the need to balance a number of competing values, especially: accurate reflection of implied metres, accurate representations of durations, performability, and legibility. These values are frequently at odds with one another. For example, aiming to produce transcriptions with the highest possible degree of temporal accuracy (as a computer program might) can easily result in notation that is so complex as to be unintelligible and unperformable. Conversely, oversimplifying the rhythm for the sake of intelligibility can produce notation that is so inaccurate as to rob the music of the speech-like quality that is the ultimate goal of the transcription. In trying to strike the right balance, we frequently employed devices including meter changes, tempo changes, asymmetrical meters (containing beats of different lengths), syncopations, and tuplet subdivisions. Finally, we used the indication ‘speech rubato’ to indicate that, try as we might to transcribe these rhythms precisely, the notation would always deviate somewhat from the recorded speech and the performer should use their ear as their guide. Here are two examples of our notation, in (a) Gone For All Night and (b) No Barriers:

Deciding which metre(s) to use posed unique and interesting challenges. In traditional musical notation, we may often think of metres as prescribing patterns of strong and weak beats: 3/4 time prescribes a strong-weak-weak pattern, 4/4 prescribes strong-weak-medium-weak, and so forth. But from the listeners’ perspective, it is not the metre that prescribes the accent pattern, it is the accent pattern that creates the metre. For example, it is not because the music is in 3/4 time that we feel every third beat as strong; rather, it is because we feel every third beat as strong that the music is perceived as being in 3/4 time. A pattern of quarter notes notated with a 4/4 time signature but performed with an accent on every third beat will still be perceived in 3/4. In a simple example such as this it may seem like semantic hair-splitting to consider in which direction this relationship runs, but the import of the question becomes clearer when notating complex rhythms such as those found in speech. Theoretically, a musical rhythm can be notated in many different metres, perhaps in any metre. For example, here is “the same” rhythm notated in (a) 4/4, (b) 3/4, (c) 6/8, and (d) 7/16:

Although these rhythms are identical in terms of their durational patterns, it may be objected that they are not “the same” at all, because the different metres prescribe different accent patterns, and therefore they will not be felt the same way. This is correct, and it underscores the potential for discrepancy between musical notation and musical experience with respect to metre. Regardless of the time signature in which the rhythm is notated, the metre that the rhythm is really in—from a perceptual point of view—depends on where the accents are felt, and what emergent patterns they may imply. Therefore, when deciding how to transcribe a complex rhythm such as a speech rhythm, the transcriber-composer must not merely ask in what metre can it be notated: it can be notated in many different metres. The more important question is what metre(s) best capture(s) how the rhythm’s accent patterns are felt. If the notated metres accurately reflect the felt accent patterns of the speech rhythms, they will help performers and accurately reflect the experiences of listeners. If the notated metres do not reflect the felt accent patterns of the speech rhythms, they will hinder performers and contradict the experiences of listeners.

A final note on speech rhythm: some scholars, notably Ani Patel, have disputed the idea that speech is organized around a regular (i.e., periodic) pulse at all, drawing on many empirical findings to conclude that “the evidence...suggests that the case for periodicity in speech is extremely weak...the study of speech rhythm requires conceptually decoupling ‘rhythm’ and ‘periodicity’” (pp.149-150), and that this points to a key difference between music and speech, i.e., that periodicity “is widespread in musical rhythm but lacking in speech rhythm” (p.177). Based on our experiences in this project, we agree with Patel’s assertion at a macro level. Having spent many hours transcribing diverse speech rhythms, we found that there is rarely a regular pulse or recurring accent pattern for very long, and that therefore frequent changes of metre and/or tempo are required. This is what makes transcribing speech rhythm into musical notation so challenging. But we also discovered that clear pulses and meters do appear spontaneously in speech at local levels. They are usually sustained only briefly, lasting at most two or three bars before dissolving. But they certainly do exist, and they provided some of the most musically useful and exciting moments in our recordings. Here are some examples (Fred, Henry, Maureen), alongside our rhythmic transcriptions:

Such anecdotal evidence obviously does not provide a statistical counterpoint to Patel’s extensive research on this subject, but we believe they demonstrate that, at least from a musical point of view, the idea of periodicity in speech need not be abandoned entirely.

3.3. Harmonic transcription

Computer analysis can reveal a sound’s full spectrum, and in the case of harmonic sounds such as the human voice, that spectrum consists of clearly defined partials that can be polyphonically orchestrated. This is a foundational principle of Spectralism, demonstrated abundantly in pieces such as Gérard Grisey’s Partiels (1975) and Tristan Murail’s Désintégrations (1982-83) as well as pieces by Harvey, Wallin, Ablinger (see 1.1.3.) and many others. This procedure has been thoroughly documented in the scholarship and does not require much further comment here, except to note that in selecting vocal harmonics and formants to transcribe for the guitar, we found the software Praat useful. Designed primarily for phonetic study, Praat produces a variety of useful analyses of spectra, pitches, formants, and other acoustical properties of speech.

3.4. Timbral transcription

As noted in 1.3., altering the pluck position of guitar notes modifies the timbre analogously to spoken vowels. This opens interesting possibilities for speech-based music for the guitar, as it is possible to transcribe something of the timbres of speech in tandem with its pitches and rhythms. We explored these possibilities in this project, drawing on Caroline Traube’s acoustical research (2004) and applying it to composition. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to do so.

Traube presents the following diagram, which uses IPA symbols to match pluck positions to vowel timbres.

We worked with Traube to adopt a modified version of her system, indicating a set of five vowels and specifying the corresponding pluck positions in centimeters from the bridge:

We adopted the IPA symbols as notational elements, placing them above notes in the score to indicate approximately where to pluck. This requires the performer to memorize the pluck positions corresponding with each symbol, but it also constantly reminds them of the vowel analogies that are the goal of the notation. This may motivate them to make subtle adjustments where necessary to achieve better tone colours for the analogies: if, for example, they find that a slightly different pluck position produces a better vowel timbre because of the string or fret position, they are free to modify it accordingly. This is why we felt that IPA symbols were a better notational choice than numerical values in centimeters or generic terms such as SP and ST.

Another unusual aspect of our notation is the frequency and rapidity with which pluck positions change. While this introduces difficult technical challenges for the performer, it mirrors the changes of vowels in the syllables of speech, and—in our judgment—makes for a more convincing speech-like quality. Here is an example of the same speech melody played first in an ordinario pluck position and then with changing pluck positions to imitate the changing vowels:

Since our goal was to capture the colours of the dialects represented in our recordings, pluck positions needed to match the specific dialectal realizations of vowels, which did not always match how the vowels look on the page. For example, in a word like ‘sent,’ the pluck position could be in several different places depending on the vowel realization in the dialect of the speaker (e in S-NLE, I in I-NLE, a in B-NLE; see 1.4.). Accordingly, transcribing the timbres required careful listening and choosing pluck positions based on what we heard rather than what we assumed about the phonetic make-ups of words. Also, since not all vowels are available within our system, and since in some cases the syllables of speech change too fast for the performer to mirror them with pluck position changes, preparing these timbral transcriptions often involved compromise solutions.

Here is an example of our notated timbral transcription in It’s Our Own:

3.5. Electronic processes

For three of the pieces on the album, we employed additional electronic processes to manipulate the speech recordings, producing new sounds to enhance the musical textures. These included (3.5.1.) concatenative synthesis, (3.5.2.) partial extraction, and (3.5.3.) soundscape composition involving a number of common techniques such as time stretch, transposition, and granular synthesis.

3.5.1. Concatenative synthesis

For concatenative synthesis we used the Max patch CatART, which, as described on the IRCAM page that distributes it, “plays grains from a large corpus of segmented and descriptor-analysed sounds according to proximity to a target position in the descriptor space” ( retrieved May 4, 2023). In our case, the corpus was a library we created by recording all of the notes on the classical guitar one at a time, and the target was provided by speech samples from our interviews. CatART enables the user to customize the parameters by which the corpus is reordered to approximate the target, such as pitch, amplitude, spectral centroid, and so forth. After some experimenting, we found that we liked the results of weighting pitch-tracking most heavily, applying separate concatenations to the first four formants of the speech samples and then superimposing them with a DAW (Reaper). The process is similar in principle to Peter Ablinger’s talking piano (see 1.1.3.). The results may fall short of intelligibility but preserve some recognizable features of the original speech in a spectral, other-worldly guitar-voice hybrid that captured the eerie effect we sought to create (original speech clip and resynthesized version).

3.5.2. Partial extraction

We used another software, SPEAR (Sinusoidal Partial Editing Analysis and Resynthesis), to extract partials from the speech sounds so that we could use them elsewhere in the musical textures. SPEAR analyzes all sound signals as a composite of sinusoidal partials which can be selected, played, exported, and manipulated in various ways, either singularly or in customizable groups. The extracted partials provided a useful link between vocal timbres and guitar timbres, as they are derived from the voice but sound similar to certain timbres of the electric guitar, especially when played with a slide (original speech clip and resynthesized version). We also used SPEAR as a model for customized microtonal notation (see 4.5.3.).

3.5.3. Other processes

In creating sound effects and textures for several of the pieces, we used a number of other common sound editing and processing procedures:

3.5.3.1. Attack removal. Simply replacing the attack portion of a guitar note with a niente fade-in gives it a completely different character, comparable to an organ or a reed instrument.

3.5.3.2. Time stretch. Extreme time stretching of vocal sounds, including speech and non-phonated sounds, can transform their character to the point where their original sources can no longer be recognized, especially when combined with transposition.

3.5.3.3. Spectral freeze. This technique is used to arrest a particular point in a word or syllable for an unnaturally long time, disrupting its phonetic proportions.

3.5.3.4. Granular synthesis. Short fragments of vocalizations or guitar sounds are randomly selected within a specified range and randomly transposed and superimposed, creating grainy, cloud-like sound textures of varying densities that are audibly related to, but abstracted from, their original sources.

3.5.3.5. Collage. Superposition of large numbers of sounds, including conventional folksong melodies and extended techniques on the guitar and the prepared piano, creates sound mass textures.

Figure 19: A speech clip and three processed versions: "Ghosts" processed with spectral freeze, "Here" with extreme time-stretch (100x), "Here" extreme time-stretched and transposed down two octaves

4. The album

Our album, One Foot in the Past, was recorded with the aid of a Strategic Project grant and a Research-Creation grant from ACTOR, as well as a postdoctoral Research-Creation fellowship from FRQSC.

The 14 tracks on the album fit into several categories: (4.1.) folksong transcriptions, (4.2.) other instrumental tracks, (4.3.) recitations, (4.4.) tracks with instruments and speech, and (4.5.) tracks with instruments, speech, and electronics. Scores for all but the recitations are distributed through the Canadian Music Centre. Following descriptions of the pieces in each category, we provide information about (4.6.) the recording process.

4.1 Folksong transcriptions

Two of the tracks, Interlude: River Driver and Postlude: The Shabby Genteel, are solo guitar arrangements of tunes transcribed from the MacEdward Leach archive (see 1.2.1.). They are straightforward, tonal arrangements in a traditional folk style. We tried to stay true to the original archival vocal performances: in some cases, there were notes that we suspected were “wrong,” but we kept them intact and harmonized them accordingly. We also added ornamentation similar to how the singers did, and followed their leads with respect to pacing, adding fermatas where they took pauses and omitting them where they did not.

This video of River Driver was released prior to the album recording:

4.2 Other instrumental tracks

4.2.1. Folk Suite

This piece, for flute and guitar, was originally commissioned for cello and marimba by Stick&Bow (Krystina Marcoux and Juan Sebastian Delgado). The original version appears on their album Resonance (Leaf Music, 2019). Another recording of the flute-guitar version appears on the album Wanderlust by Adam Cicchillitti and Lara Deutsch (Leaf Music, 2023).

Folk Suite seeks to capture not just folk melodies, modes, and rhythms, but also the vast range of tones and timbres, the nuances of narrative delivery, the intricate ornamentation, and the push and pull of time that are enshrined in the oral tradition Newfoundland folk music. Contemporary notational techniques offer new ways of capturing such idiosyncracies, and the flute and guitar are ideally suited to conveying them. Folk Suite’s six miniatures each attempt to capture a different aspect of Newfoundland folk music. The tunes are all original, but they deliberately emulate the vocal and instrumental genres for which each miniature is titled.

overture emulates the sonorities of folk instruments such as the Celtic harp and the tin whistle;

air emulates accompanied folk singing, with the flute taking the role of a lyrical female voice and the guitar taking the role of an accompanying string instrument with echoes of the historical lute song;

ceilidh emulates the joyful energy of Newfoundland kitchen parties, which often feature improvised percussion on instruments such as the spoons or the ugly stick;

ballad emulates a cappella folk singing, with the flute taking the role of a male voice with much freedom of pacing for narrative delivery;

jig emulates group folk singing in a party setting; and

reel emulates fiddle music and folk dancing.

4.2.2. fantaisie harmonique

This is the most abstract piece on the album, though it shares musical elements in common with some of the other pieces. A separate in-depth discussion of this piece is published on ACTOR’s Timbre and Orchestration Resource: The "Paradoxical Complexity" of Sound Masses.

4.3. Recitations

Four album tracks contain no instrumental music and consist entirely of recorded speech. These are recitations of selected lyrics from four folksongs from the MacEdward Leech archive (see 1.2.1. and 2.1.1.). Each recitation is compiled from several different speakers reciting, so that the listener hears the continuity of the story, the rhyme scheme, and the poetic foot of the lyrics, but divided between contrasting voices and dialects. The recitations function as preludes to larger pieces dealing with related themes, similar to how they functioned as precursors to larger conversations in our interviews.

4.3.1. Kelly and the Ghost features a ghost story, and leads into we never told nobody which focuses on Newfoundland’s folkloric tradition of ghost and faerie stories.

4.3.2. River Driver addresses yearning for home, telling the story of a young man who left Newfoundland to work in Québec, and leads into It’s Our Own which draws connections between Newfoundland and Québec in connection to dialect and community identity.

4.3.3. Butter and Cheese features a comical “tall tale,” and leads into Gone for All Night which creates the kind of party atmosphere where such storytelling might take place.

4.3.4. The Shabby Genteel addresses making the most of what you have, and leads into Take Me Back which reflects on technology, change, and the gradual disappearance of the old way of life.

4.4. Tracks with instruments and recorded speech

Three of the pieces contain only recorded speech and instrumental music (mostly guitar). Composing them involved compiling selected speech clips with a particular theme in mind, ordering the clips to create musical and narrative interest, and adding a guitar part that musicalized the speech. Each of the three steps was an extended creative process in its own right.

Compiling the clips was something vaguely akin to journalism: combing through a mass of interviews to select a relatively small number of clips to tell an overarching story that, while it is made up of the words of interviewees, is crafted and curated by the composer. Ordering the clips involved countless choices: how to introduce narrative elements for effective storytelling; how to create interesting proportions between clips ranging from very short (sometimes just single words or very short phrases in rapid succession) to much longer (monologue-type excerpts); how to harness the melodic and rhythmic qualities of the speech in creating musical forms; how to showcase the variety of dialects represented in the interviews; and so forth.

After the “mash-ups” had been pieced together, musicalizing them through the addition of the guitar was the stage closest to conventional composition: it involved putting notes on the page. In addition to the technical considerations discussed above (see 3.), there were many additional artistic decisions to be made. How to deploy unaccompanied speech, solo guitar passages, and guitar-speech combinations in the overall musical form? For the combinations, which approach to use in any given context (percussive-rhythmic transcription, monophonic melodic transcription at pitch with or without timbral transcription, monophonic melodic transcription in another octave, harmonized melodic transcription, harmonic shadowing in which a select few syllables are chosen for sustained pitches while the others are untranscribed, non-transcription combinations in which the guitar plays phonetically unrelated music to create a soundtrack to the speech, etc.)? For the solo guitar passages, how to connect them to the speech-based musical context?

One of the pleasing surprises of this process was discovering just how uncannily similar the motifs and melodies of speech often are to those of music, allowing many opportunities to “riff” on a speech melody to produce music that sounds authentic despite its “non-musical” origin. We were also delighted to discover just how frequently and convincingly the speech clips implied tonal harmonizations.

4.4.1. It’s Our Own

The opening track of the album, It’s Our Own sets the tone and theme for all that follows. It is organized in three sections. The first of these features people expressing the connection they feel to home in terms that border on spiritual. It is wistful, nostalgic, and relatively sparse in its musical setting, prioritizing harmonic shadowing, giving the music and the speech space to breathe. The second section addresses the variety of dialects in Newfoundland, and the joy and pride they inspire in residents of the province. The energy picks up considerably with some folk-infused virtuosic guitar music that grows out of speech motives. The third section resumes a more pensive mood as people reflect on the shame that can be felt in relation to dialects, which can sometimes be used to mock, deride, and bully people whose speech patterns deviate from the norm, casting them as less intelligent or of lower social status. The piece ends with a defiant statement of pride in Newfoundland dialect: “it’s our own.”

4.4.2. No Barriers

This piece reflects on the role of the French language in Newfoundland and Québec, and is the only piece on the album to include French speech excerpts (see 2.2.). This piece was autobiographically important to us as we both grew up in Newfoundland and now live in Québec, the two provinces whose identities are tied to speech, language, and dialect perhaps more than any others. We believe that pride and identity in dialect is something that Newfoundlanders and the Québecois have in common. The chosen clips tell a story of shared values across cultural differences.

4.4.3. Gone for All Night

Dancing, parties, music, and storytelling are the subjects of this high-energy piece, Gone for All Night. There was much joy in our interviewees’ voices when they told us about kitchen parties, shed parties, mummering, square dancing, the host of musical instruments found in peoples’ homes, and community figures who were famous for being great dancers, singers, and players. This piece incorporates several folk tunes, including quoted tunes and original tunes composed in established folk styles. It also makes greater use of tonality than some of the other album tracks, both through harmonizations of the folk tunes and through the tonal implications of the speech transcriptions. This piece is also distinct on the album in using the most instrumental sounds besides the guitar, including accordion, tin whistle, and improvised percussion.

4.5 Tracks with instruments, speech, and electronics

Three of the longest album tracks involved electronics as well as speech and instruments. They vary with respect to their themes, approaches to speech transcription (or lack thereof), sonic source material, electronic techniques, and overall effects.

4.5.1. we never told nobody

This piece, we never told nobody, focuses on ghost and faerie stories, cornerstones of Newfoundland folklore. We asked people about supernatural storytelling in their communities, and were thrilled when many of them not only described the tradition in general but also recounted specific stories. Some of these stories involved similar themes—for example, unexplained lights in the dark, calling on priests to dispel apparitions, mysterious circumstances preceding or following a death in the community—which led to some natural groupings in the narrative and musical form. The stories invoked sound images in some cases (e.g., “there was this thump, thump, thump” ... “three knocks would indicate that somebody was going to die”), and in other cases provided compelling invitations for cross-modal correspondences (e.g., “a light in the bight appeared” ... “all the woods lit up with a light like an orange fire”) which we took as invitations to incorporate various percussive sounds and electronic timbres.

The sources for all sounds in the electronics are derived from guitars and voices, transformed in various ways. Concatenative synthesis (see 3.5.1.) figures prominently, producing a spectral guitar-voice that is other-worldly but vaguely recognizable at the same time. Abstracted connections with speech are also present in several other ways: vowel formants (1.3.2.) are used as filters for some of the percussion sounds; some of the speech clips are treated with extreme time stretch and transposition that make their source virtually impossible to recognize (3.5.3.2.); spectral freeze is used to create supernatural interjections in otherwise normal spoken phrases (3.5.3.3.), and melodic (3.1.), rhythmic (3.2.), and timbral (3.4.) transcription in the guitar part link music and speech here as in other album tracks. A major section of the piece features two extended ghost stories set against an aleatoric “soundtrack” of scordatura harmonics, creating a link to the following piece fantaisie harmonique.

4.5.2. One Foot in the Past

The battle of Beaumont Hamel in World War I (1916) is a singularly painful event in the history of Newfoundland, so much so that it continues to affect many residents of the province today. Nearly the entire Newfoundland Regiment was wiped out in a matter of minutes. For what was then a tiny country, it was devastating beyond words to lose virtually a whole generation of young men. The hundredth anniversary of the battle was in 2016, the year after our tour. We asked residents of the province to tell us about what the battle means to them today: a compilation of their reflections is featured in One Foot in the Past. One of the songs that an interviewee spontaneously sang for us (see 2.1.3.) happened to chronicle the battle of Beaumont Hamel, so we decided to begin One Foot in the Past with several verses from this song. We ended the piece with another song that a different interviewee sang. We felt that the two songs compliment each other well; we could imagine the first song from the perspective of a soldier in Beaumont Hamel, and the second from the perspective of a loved one back home.

This piece is unique among the speech-based pieces on the album in that it contains no speech transcription. Bringing to light the perceptions of Newfoundlanders today of a historical event, it is a kind of musicalized documentary, or a narrativized soundscape piece. Several familiar electroacoustic techniques are used in transforming the vocal and guitar sounds, including attack removal (see 3.5.3.1.), granular synthesis (3.5.3.4.), and so forth. Sound mass textures, which can be very acoustically complex but are perceptually simple as an overwhelming number of sounds group together into a single unit (see Noble & McAdams, 2020), are a key feature of this piece. They are made from collages (3.5.3.5.) of clips of folksong fragments at first, and of noisy and dystonic contemporary techniques later. The transition from (presumably familiar) folksongs to (presumably unfamiliar) extended techniques signifies the Newfoundland Regiment’s departure from home and arrival in a hostile foreign land.

4.5.3. Take Me Back

A recurring theme in our interviews was change, and the role of technology in transforming the old way of life. We compiled reflections on this nostalgic subject for the final speech-based piece on the album, Take Me Back, which is named for the first line of one of the most famous folksongs of Newfoundland, Let Me Fish Off Cape St. Mary’s. The sense of nostalgia is emulated musically in the first moments of the piece by a backward-looking trajectory that begins with a collage of electronic sounds and gradually transitions to a natural soundscape of sea birds and the ocean.

This piece is also of the documentary-soundscape variety. It is materially different in some ways from the other tracks on the album. It is performed on the electric guitar, which offers different opportunities than the classical guitar: longer and more even sustain, more precise and variable dynamic control using a volume pedal, easier and more precise microtonal shading using a slide, and effects such as delay pedal and distortion. Speech transcription is important in the guitar writing in this piece, but in a less rhythmic, more ambient way than in the others. While lengthier passages of speech occupy the foreground, particular words or phrases extracted from those passages repeat in the middleground and are transcribed for the guitar. The type of transcription is less focused on rhythmic and melodic momentum, and more on timbral and harmonic prolongation, creating a sense of sinking into the sound and slowing the felt pace of time passing.

The middle section of the piece uses the guitar slide to follow the partials of a repeated speech clip, allowing the guitar and the voice to nearly fuse together. To achieve this effectively, we needed to create a customized kind of zoomed-in notation, adapted from visual representations produced by SPEAR (see 3.5.2.). Each “staff line” represents a semitone and a complex glissando line traces a microtonal path following the vocal partial. The thickness of the line represents volume and is controlled with a volume pedal.

The final section of the piece involves partial extraction, also produced by SPEAR. Partials are presented singularly or in groups, manipulated in various ways, in a dilated time scale. The guitar plays chords transcribed from the spectra of the speaker’s voice at key moments, and the combination of the extracted partials and the guitar chords extend and melt the speaker’s voice into an ambient wash of sound that permeates the section, gradually ceding to a natural soundscape at the end of the piece.

4.6. The recordings

Recording took place primarily at McGill University, with one session in the Multi-Media Room (MMR) and two others in its adjacent studios. Folk Suite was recorded in New Zealand. Steve Cowan performed all of the guitar parts on the album, constituting by far the largest instrumental contribution. Jason Noble played piano and Hannah Darroch played flutes. As noted above, some additional vocal and instrumental performances, in addition to the many excerpts of recorded speech, were captured on our tour: the performers and speakers remain anonymous for confidentiality reasons, as per the consent forms signed by all interviewees as a requirement of McGill University’s ethics approval for this project. Denis Martin was the recording engineer for fantaisie harmonique, with recording assistants William Sylvain and Nick Pelletier. For all other tracks, Carolina Rodríguez was the recording engineer, with recording assistant Ying-Ying Zhang and additional assistance from Nathan Cann. We give special thanks to Martha de Francisco, Julien Boissinot and Sylvain Pohu who assisted and advised before and during the recording.

For the recording session in MMR, several recording techniques were used to allow for more flexibility during the post production process. Each required a different approach to spatial mixing, some stemming from an acoustical capture approach, and others from a more acousmatic perspective with the positioning of different layers in the 3D space. The techniques included 3D microphone multichannel arrays, high-order ambisonics capture, binaural capture, and mono spots. In the final recording session, informed by the previous experiences, only the 3D microphone arrays and spots were kept. However, the recording was performed in the Immersive Lab (IMLAB) using the new Virtual Acoustics Technology (VAT) System comprised of precisely positioned microphones and omnidirectional speaker sources. These enhance the acoustics by taking real-time microphone capture and convolving it with spatial impulse responses of physical spaces. The result of this operation is then played back in the space and can be tailored to the preference of the performer(s), the producer(s), and the recording artist(s).

Some of the pieces with electronics tracks required recomposition work on the electronics tracks using session recordings as source material: for these, the recorded microphone sources were narrowed down. For the other pieces, the full channel count was kept, evaluated in the editing and mixing phase, based on considerations including the location of sources, the clarity of melodic and rhythmic lines, and the sensation of acoustic space.

Works Cited

Clarke, Sandra. 2010. Dialects of English : Newfoundland and Labrador English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Cowan, Steven. 2019. “Between Speech and Music: Composing for Guitar with Dialectal Patterns.” Doctoral dissertation, McGill University Libraries. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/papers/dr26z277t.

Deutsch, Diana. N.D. “Speech-to-Song Illusion.” University of California at San Diego. Accessed May 9, 2023. https://deutsch.ucsd.edu/psychology/pages.php?i=212.

Folksongs of Atlantic Canada: From the collections of MacEdward Leach. 2022. Memorial University of Newfoundland Folklore and Language Archive. Accessed May 11, 2023. https://mmap.mun.ca/folk-songs-of-atlantic-canada/home.

Noble, Jason. 2022. “The Career of Metaphor Hypothesis and Vocality in Contemporary Music.” Interdisciplinary Science Reviews 47 (2): 259–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/03080188.2022.2035108.

Noble, Jason. 2020. “Simplicity out of complexity out of simplicity: The ‘paradoxical complexity’ of massed sonorities.” Timbre and Orchestration Resource. ACTOR. https://timbreandorchestration.org/writings/research-creation-series/paradoxical-complexity#part3

Noble, Jason and Steve Cowan. 2020. “Timbre-Based Composition for the Guitar A Non-guitarist’s Approach to Mapping and Notation.” Soundboard Scholar 6, pp.22–35. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/sbs/vol6/iss1/7/.

Noble, Jason and Steven Cowan. 2017. “The Music of Dialect.” Research Alive series, Schulich School of Music, McGill University. Video, 1:04:20. https://youtu.be/wAJ0UX3t4Bs.

Noble, Jason, and Stephen McAdams. 2020. “Sound Mass, Auditory Perception, and ‘Post-Tone’ Music.” Journal of New Music Research 49 (3): 231–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/09298215.2020.1749673.

Patel, Aniruddh D. 2008. Music, Language, and the Brain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Phonologie de français contemporaine (Base PFC publique). N.D. Projet Floral. Accessed May 11, 2023 https://public.projet-pfc.net/.

{Sound Music Movement} Interaction. 2023. Ircam. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://ismm.ircam.fr/catart/.

The Dialect Atlas of Newfoundland and Labrador. N.D. Memorial University of Newfoundland. Accessed May 9, 2023. https://dialectatlas.mun.ca/.

Traube, Caroline. 2004. “An Interdisciplinary Study of the Timbre of the Classical Guitar.” Dissertation, McGill University Libraries.

Funding

This project was funded in part by the Fonds de recherche du Québec and the Analysis, Creation, and Teaching of Orchestration Project.