A decade of neglect has transformed Ontario Place into an accidental playground. As you will discover in our cover section, what was once intended as a provincial showcase has evolved into a destination for walkers, cyclists, swimmers, paddleboarders, partiers, birdwatchers, lake watchers, and human watchers, along with movie- and concert-goers to its more established venues. All, as Shawn Micallef notes, with an unusual-for-Toronto legacy of attractive, functional washrooms.

In this role, Ontario Place can be thought of as the mirror image and bookend, on the western side of Toronto’s harbour, of what has been dubbed the “accidental wilderness” of the Leslie Street Spit to the east.

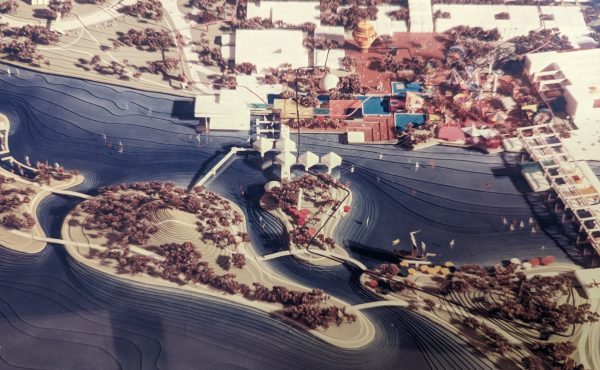

Like the Spit, Ontario Place is an artificial land mass extended out from Toronto’s shoreline into Lake Ontario. And, since its official closure in 2012, it has, like the Spit, been colonized unofficially. In the Spit’s case, it was nature that did the colonizing – plants, birds, animals, and insects gradually settled and took it over, transforming it into an unplanned wilderness. In the case of Ontario Place, while nature (especially birds) has played its part, as Francesca Bouaoun describes, the colonization and evolution has been more at the hands of humans. People have discovered this largely open space, with its lakeshore, parklands, space-age architecture, and charming ruins of abandoned rides, and have re-imagined it into their own recreational space, one much-needed amid the burgeoning population near the waterfront and the stresses of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Ontario Place was always intended to be recreational, but what the closure of the paid recreational sections revealed was that its best use is as a public space, a park where people can improvise their own pleasures. Even its isolation is a boon – without nearby residents, there’s no worry that how it’s being used will disturb anyone. Like the Spit, again, it’s an escape from the city that’s right at the city’s door.

The provincial government has plans to wrest the space back to private use and impose grand schemes on it – just as governments once had plans to come up with “practical” uses for the Leslie Street Spit. It’s the classic urban conflict between organic evolution from below versus planning imposed from above. As with the Spit, it will be up to the people of Toronto to stand fast and insist on letting this outcrop’s own messy path emerge naturally as people use it.

Some of the features in our front section also speak to the situation of Ontario Place. Jay Cockburn wonders if the “right to roam” the countryside that he experienced growing up in England could be transplanted to Canada. In England, the right to roam didn’t just happen. It was the result of decades of campaigning from the grassroots, as ramblers insisted on their right to use England’s natural environment for the enjoyment of all, not just private property owners – much as everyday visitors have developed unplanned ways to enjoy Ontario Place.

Meanwhile, Sarah Hood explores the development of the remarkable StreetARToronto program on its tenth anniversary. The program grew out of the realization that the way to deal with graffiti was not to fight it, but to embrace it. Graffiti was a sign that blank walls and grey infrastructure need life. Rather than wasting time and money making walls boring again, the City began paying street artists to cover them with art. The result was a more colourful, vibrant city and an ecosystem of talented artists. The City, in other words, paid attention to how its residents were reshaping the city, and built on that organic process rather than suppressing it. Likewise, Toronto’s residents have pointed the way to how to make Ontario Place thrive – it’s up to governments to build on that rather than fighting it.

Our big picture, meanwhile, is a striking example of StreetARToronto’s patronage. It is Toronto’s first tactile mural – an image that people without sight can experience through touch. When artist Leyland Adams asked people who had lost their sight what they missed, a common refrain was the sunset from Toronto Islands. It’s a reminder that the waterfront is fundamental to Toronto’s identity and mythology. It needs to be accessible to everyone in the city.

Pick up the new issue at the Spacing Store, online, or on newsstands.

2 comments

Almost all of the great StreetARToronto works in my areas were defaced pretty quickly. Sorry cool street murals do not stop visual vandalism.

Scott: Must be your area and anecdotal. Most of what I’ve seen across the city has lasted a long time. The new murals are lasting longer too because the city applies a really good coating of a repellant when the work is finished. Anyways, they are not meant to be permanent.