Indigenous-led climate research station rebuilds after October wildfire

Wildfire smoke looms over the Scotty Creek tower site. Photo by Joëlle Voglimacci-Stephanopoli / Université de Montréal

Arctic Communications Specialist, Woodwell Climate Research Center

After Canada’s Scotty Creek Research Station was devastated by a late-season wildfire, Permafrost Pathways is helping to rebuild

In October 2022, Scotty Creek Research Station—a prominent climate research facility in the Northwest Territories (NWT) of Canada—was almost entirely consumed by an unusually late-season wildfire. With five out of nine of the station’s buildings destroyed and an estimated two million dollars of damage to onsite housing, research equipment, solar panels, and lab space, the fire was a “gut punch” to one of the only Indigenous-led climate research stations in the world. But, with support from Permafrost Pathways, the Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ First Nation (LKFN) who now lead the facility are focusing their attention on rebuilding.

Above: Smoke from the nearby fire descends on Scotty Creek. Photo by Mason Dominico

A cruel irony: when the impacts of climate change thwart climate research

The fire that destroyed Scotty Creek Research Station had been active for almost 100 days before finally reaching the camp. Usually, the area sees rain or snow for almost half of the month in October, and historically, it has even snowed as much as 12 inches with temperatures sometimes dropping as low as negative two degrees Fahrenheit (-19 degrees Celsius). But drier conditions, abnormally warm weather, and heavy winds in late 2022 led to an extended and extraordinarily active fire season in the NWT—which exceeded its 10-year average of total fires burned, with over 1.3 million acres affected by fire.

Map by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

“It was just heartbreaking,” William Alger, LKFN’s lead Dehcho guardian at Scotty Creek told CKLB Radio after being the first to witness the extensive destruction left in the fire’s wake last fall. But now, “it’s just a matter of picking up the pieces and figuring out where we go from here,” Alger said.

Climate change is making it harder to conduct climate research, a harsh reality that the fire at Scotty Creek tragically represents. The obstruction of data collection and ecological stewardship caused by frequent environmental disasters is becoming a recurring setback, presenting a daunting challenge for carrying out this work in a perpetually warming world.

Top: Wildfire burning through the boreal and permafrost landscape getting closer to the research facility.

Bottom: Wildfire smoke hanging over Goose Lake and Scotty Creek Research Station. Photos by Mason Dominico

“I can’t help but notice the irony that a subarctic research station dedicated to understanding climate change burned down in mid-October due to a wildfire,” William Quinton, a professor at Wilfrid Laurier University and the original founder of Scotty Creek Research Station, said in an interview for CBC News.

The unusual time of year made it difficult to attack the fire, as temperatures suddenly plummeted and strong winds began to pick up. For several days leading up to the weekend of October 15th, the Scotty Creek team anxiously watched the fire burn closer and closer to the camp, mentally preparing for the worst but hoping for the best.

Total burn extent animation by Greg Fiske / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Unfortunately, common techniques for combating wildfire, such as cutting fire breaks and setting up sprinklers, failed when the cold snap led to the territory’s environment and natural resources department removing sprinkler systems they feared would freeze—drawing criticism from LKFN—and changes in wind direction forced the early evacuation of research teams and firefighting crews helping out on the ground. Additionally, helicopters trying to combat the flames from the air were unable to pull water from surrounding water bodies that had begun to freeze over.

“When we’re fighting fires and protecting structures, it is highly unusual for there to be the threat of freezing temperatures,” Mike Westwick, a wildfire information officer for the territory wrote in an email to CBC News.

Top: The Scotty Creek tower site after the wildfire tore through the research camp. Photo by Mason Dominico

Bottom: Université de Montréal Researcher Gabriel Hould Gosselin working on the carbon flux tower at Scotty Creek as the wildfire approaches the camp. Photo by Joëlle Voglimacci-Stephanopoli

Impacts from the burning of Scotty Creek extend far beyond the research station and will have a ripple effect on the economies of nearby communities that benefit from the droves of international researchers coming to this unique region every year to study environmental change caused by rapid warming. The visitors Scotty Creek draws to the Fort Simpson area provide steady income to local businesses including hotels, grocery stores, and airlines.

“The loss of Scotty Creek facilities is going to have a series of impacts that will have an ongoing effect on our already delicate local economy. Our hotels, bed and breakfasts, and charter airlines will take the biggest hit. Important climate change research, youth education, and the economic activities that are part of keeping it going will now be temporarily halted” LKFN Chief Kele Antoine said in a press release.

Aerial view of the Scotty Creek research camp before wildfire damage. Photo by Scotty Creek Research Station

A remote research station with worldwide influence

Since its founding in 1999, Scotty Creek has been a place to study the various impacts of climate change and permafrost thaw on delicate northern ecosystems in the Dehcho (“big river”) region where the facility is based. The station included an all-season research camp that doubled as an outdoor classroom and laboratory space. It established itself as one of Canada’s major northern research stations and the data collected there over the course of decades is now used by organizations across the globe, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Top: Scotty Creek Research Station beneath the aurora during winter. Photo courtesy of Scotty Creek Research Station

Bottom: Scotty Creek Research Station next to Goose Lake before the 2022 fire. Photo courtesy of Scotty Creek Research Station

In the years since its founding, the Scotty Creek Research Station experienced extreme landscape change firsthand—in 2012 they relocated due to thawing permafrost threatening the facility’s infrastructure. This type of fast-paced ecological change, known all too well by communities in the Dehcho and the rest of the Arctic, is what drew researchers across environmental disciplines to Scotty Creek, sparking new lines of scientific inquiry, educating young climate scientists, and even inspiring artists like Dominik Heilig to adapt the unique history of Scotty Creek into a journalistic graphic novel.

Watch the Scotty Creek short film by the Dehcho Collaborative on Permafrost below:

The station marked another historical milestone in August 2022, just months before the fire, when a special ceremony was held to transfer ownership of the station to LKFN—making Scotty Creek Canada’s first Indigenous-led climate research station, and one of just a few Indigenous-led climate research stations in the world.

Top: Scotty Creek founder William Quinton and members of LKFN commemorate Scotty Creek Research Station becoming one of the first Indigenous-led research stations. Photo courtesy of Scotty Creek Research Station

Bottom: Members of LKFN holding ceremony to celebrate Indigenous ownership of the station as of summer 2022. Photo courtesy of Scotty Creek Research Station

Indigenizing northern climate science to protect ancestral lands and traditional ways of life

Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ means “the place where the rivers come together” in the Dene Zhatie language, and Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ First Nation people are the traditional keepers of the land and water of what is now known as Fort Simpson. Guided by Dene principles and values, LKFN has committed to uplifting their culture through intergenerational education and building connections that respect their traditional language (learn how to pronounce Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ People), elder and youth voices, and their self-determination as land stewards. For LKFN, taking the lead at Scotty Creek Research Station was a new way to honor that commitment.

Video: Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ Elder Jonas Antoine describes growing up in the Dehcho region and the lessons he learned from Elders about looking after the land and preserving traditional Dene knowledge.

Listen to more Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ Elders and their stories documented by the Reel Youth media empowerment project that created these documentaries to preserve the Dene Zhatie language and pass down intergenerational knowledge amongst community youth.

LKFN’s director of lands and resources Dieter Cazon told Cabin Radio that a major goal of Scotty Creek Research Station has been to foster ethical climate research that combines Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) and western science for a more holistic, co-produced understanding of the compounding climate impacts being experienced by First Nations in the region and how to adapt to ongoing environmental change.

“This collaborative work we’re doing together is going to be the only way we’re going to figure a lot of these answers out,” Cazon told CBC News.

The western scientific approach has a fraught history of unethical and disrespectful engagement with Indigenous peoples while working on their lands. At its worst, Arctic research has exploited communities for data collection that benefited their own research, without ever returning findings back to the villages where it was conducted. Other times it has ignored them altogether, failing to meet the needs and wishes of the communities and dismissing Indigenous Knowledges as legitimate ways of knowing.

“Too often in the past, scientists like me came north and then headed south without sharing the results of what they found,” Quinton said in an interview with Yale Environment. “It led to some distrust, even pushback in some cases. Partnering with Indigenous communities has changed that. A management approach that puts them in leadership positions is also critical because it’s their land now and their livelihood that’s at stake. They can also ground-truth what we are seeing or missing.”

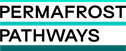

Left: William Alger, the lead Dehcho guardian at Scotty Creek and member of the LKFN, working at the tower site. Photo courtesy of Scotty Creek Research Station

Right: Fort Simpson community members sharing Indigenous knowledge with researchers during the Nahegha ndéh gondıé (“land stories for us”) event held at Scotty Creek. Photo by Stephanie Wright

According to Cazon, in the past Scotty Creek has contributed to this inequity. But the transition of ownership to LKFN places Scotty Creek among a growing movement of Indigenous-led research initiatives challenging this old model of science. Indigenous community members and researchers will collaboratively address the impacts of climate change in the circumpolar region, which Indigenous communities often face the brunt of. Any raw data now collected at the station is co-owned by LKFN. Researchers must also demonstrate an understanding of the communities they will be working in before they arrive and uphold their commitment to respect the land and local people through ethical research practices onsite.

LKFN member and lead Dehcho guardian at Scotty Creek William Alger holding the LKFN flag after surveying damage from the wildfire. Photo courtesy of Scotty Creek Research Station

From the ashes, Scotty Creek rebuilds

The important research happening at Scotty Creek stalled in the months following last year’s fire, but not for long. LKFN has already begun the rebuilding process, with an eye towards improving the station’s resiliency in the face of what have become perpetual threats to the region due to climate change.

“It’s very unlikely that this is a one-off. I’m sure that things are changing, and that we will see this again, and for that reason—we need to be prepared” Quinton told CBC News.

Top: Entrance to Scotty Creek Research Station. Photo by Dominik Heilig

Bottom: Dr. Oliver Sonnentag working on the Scotty Creek carbon flux tower in March 2023. Photo by Dominik Heilig

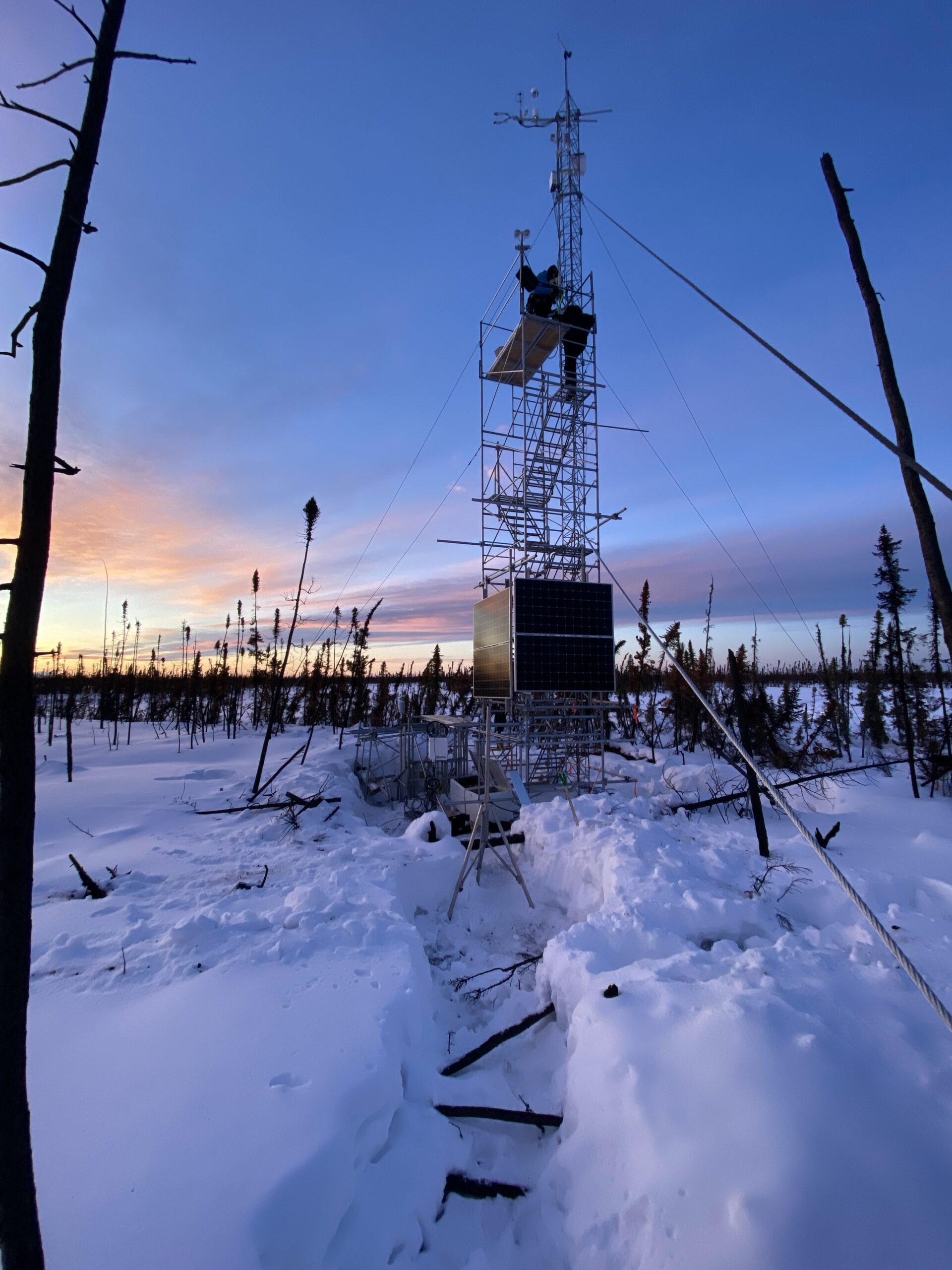

Working with Dr. Oliver Sonnentag, an associate professor at the Université de Montréal and longtime researcher at Scotty Creek, Permafrost Pathways is supporting LKFN in their efforts to rebuild Scotty Creek, primarily the reinstallation of an essential carbon monitoring tower used to measure greenhouse gas fluctuations as they move between soils, plants, and the atmosphere. Woodwell Climate’s Dr. Kyle Arndt and Marco Montemayor, members of the Permafrost Pathways carbon flux network team, spent two weeks in March assisting LKFN and Dr. Sonnentag’s team with restoring the charred tower site, which has now been resurrected and is on its way to being fully operational.

“It’s very unique and essentially unheard of to have a decade of data that predated a wildfire and then be able to rebuild in the exact same location and make a direct post-fire comparison,” Dr. Arndt said. “So, to help reassemble the tower site was an exciting opportunity for Permafrost Pathways to continue supporting LKFN and the Scotty Creek Research Station. From a scientific standpoint, getting that tower site up and running again will ultimately yield really interesting data.”

Left: A colorful northern sunrise over the Scotty Creek tower site in March 2023. Photo by Marco Montemayor / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Right: Woodwell Climate’s Dr. Kyle Arndt working on the carbon flux tower. Photo by Marco Montemayor / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Keeping this tower operational will contribute to filling persistent carbon monitoring gaps across the Arctic where 80% of the Arctic landscape is not currently represented by year-round monitoring sites because data collection in these environments is often challenging and difficult to sustain financially. Permafrost Pathways is strategically identifying and closing these data gaps by upgrading and installing new equipment across the Arctic to reduce scientific uncertainty in current carbon budgets and future projections. More complete data will drastically improve permafrost emissions estimates, removing a major barrier to their incorporation into climate policy and adaptation strategies.

Left: A restored carbon flux tower at Scotty Creek Research Station in March 2023. Photo by Marco Montemayor / Woodwell Climate Research Center

Right: Woodwell Climate’s Marco Montemayor (bottom) supporting tower site fieldwork.

Scotty Creek Research Station is an invaluable contributor to this pan-Arctic carbon monitoring network, providing essential data for a territory experiencing rapid environmental change across the region. Permafrost Pathways will continue supporting Scotty Creek throughout recovery and beyond so that the station can continue hosting visitors, and serving local communities and scientists.

“Another goal of the restored tower site is to get more Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ First Nation peoples involved with the maintenance of equipment and data collection,” Montemayor said. “This way, lines of communication are kept open, which allows for more data transparency and knowledge exchange while continuing to bring in the diverse skill sets from members of the Łı́ı́dlı̨ı̨ Kų́ę́ First Nation whose land this tower operates on.”

LKFN hopes the station will be able to partially reopen by August 2023. Although the wildfire claimed a large percentage of the research facility, Quinton said that the flames couldn’t destroy the partnerships and connections that Scotty Creek has built and nurtured over the years. “And that’s going to be the foundation on which we build and move forward.”

Go to top