“I feel (un)safe when…”: What athletes have to say about high performance culture

July 25, 2022

Highlights

- In this article, researchers present their findings about Canadian high performance athletes’ perspectives on safe and unsafe sport environments, as well as recommendations for changes

- Athletes identified coach behaviour, teammate or fellow athlete behaviour, lack of resources and an inattentive sport system as key factors contributing to unsafe sporting environments

- Implementing initiatives to target these issues can support the shift to a safer sport environment (for example, requiring coaches to undertake self-awareness and self-regulation training that promote safe coach behaviour)

Since 2018, a rapid increase in the number of reported and high publicized cases of maltreatment has catapulted safe sport to the top of the priority list for sport policymakers around the globe. Prompted by the power of the #MeToo movement, athletes have taken steps to go public with their stories and report their own experiences within the Canadian sport system. In 2019, the former Minister of Science and Sport, Kirsty Duncan, responded to these reports and called for a systematic shift in the culture of sport to eradicate issues surrounding abuse.

In response, several initiatives followed, including funding for the Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada to create an investigative unit and confidential helpline, the establishment of a Universal Code of Conduct on Maltreatment in Sport and new and updated policy for National Sport Organizations (NSOs) to reflect that code.

In 2022, the current Minister of Science and Sport, Pascale St. Onge, doubled down on safe sport, with further support to help address continuing issues that have plagued the sport system. Such issues include, but aren’t limited to: verbal, emotional, physical and sexual abuse as well as various other forms of maltreatment.

Before a meaningful culture shift can happen, Canada needs to understand current values that prevail in an unsafe culture of sport. An understanding of what a safer sport culture could, and should, look like is also needed. Athletes’ perspectives are essential for this understanding.

Over the past year (2021 to 2022), we interviewed high performance athletes across the country about their experiences with safe and unsafe sport. We talked to them in one-on-one confidential conversations about what safe sport means to them and when they feel unsafe in sport. We also asked about how a culture of safe sport might be realized.

This research is the first phase of a larger project that’s also generating an understanding of safe and unsafe sport culture from the perspective of coaches and administrators. Here, we present the project’s preliminary findings, sharing the athletes’ voice in understanding key aspects of safe (and unsafe) culture in high performance sport.

Understanding sport culture

Culture refers to the values, beliefs and assumptions that define a pattern of behaviour among individuals in a shared context (Schein, 2017). Athletes learn (and live) the culture of sport by observing and experiencing the actions of others. They observe accepted behaviours and practices, and see what practices the sport leaders reinforce. What’s accepted, or at least tolerated, and even rewarded and celebrated, reflects underlying values, beliefs and assumptions about “how things are done around here” (MacIntosh & Doherty, 2005).

Culture develops as (sport) leaders and athletes bring their ideas and ideals to the playing field and the broader sport system. Over time, certain behaviours and practices become accepted and reinforced, despite questionable outcomes. Those espoused values may be different than lived values (MacIntosh & Doherty, 2005; Schein, 2017). For example, the sport system promotes respect as a value, however, domination and hyper-competition may be sport participants’ lived values that they carried out and experienced. This may explain the unsafe culture in high performance sport despite government, Sport Canada and related agencies advocating for principles consistent with a safe environment.

Culture develops as (sport) leaders and athletes bring their ideas and ideals to the playing field and the broader sport system. Over time, certain behaviours and practices become accepted and reinforced, despite questionable outcomes. Those espoused values may be different than lived values (MacIntosh & Doherty, 2005; Schein, 2017). For example, the sport system promotes respect as a value, however, domination and hyper-competition may be sport participants’ lived values that they carried out and experienced. This may explain the unsafe culture in high performance sport despite government, Sport Canada and related agencies advocating for principles consistent with a safe environment.

It’s possible to effectively shift or change culture over time by refocusing and entrenching new and different values and behaviours (Alvesson & Svenignsonn, 2016). However, it requires an understanding of the culture’s existing undesirable aspects as well as the preferred values, beliefs and practices.

There’s mounting concern about how to create a culture that fosters excellence in participant outcomes while ensuring athlete wellness. And that concern is consistent with an athlete-focused understanding of the environments in which athletes train and participate in sport (MacIntosh, 2020). So, it’s critical to understand the athlete perspective, because ultimately, the athletes both live the culture and can help create the changes needed when given the opportunity to do so.

Our study: The athlete perspective

We interviewed 28 high performance athletes across Canada in 2021 and 2022. All athletes were 18 years of age or older and competing at (or recently retired from) the high performance level of sport. The participants included 16 athletes who self-identified as women, 11 as men and 1 participant preferred not to disclose.

The athletes represented 16 sports, including summer and winter, team and individual and able-bodied and parasport. The athletes’ highest level of engagement included major international sporting events, such as the Pan American and Para Pan American Games, Commonwealth Games, World Championships, Olympic and Paralympic Games.

We used a trauma-informed interviewing approach in our virtual conversations with athletes about safe and unsafe sport environments and mechanisms to shift the culture within the Canada sport system.

The contexts of unsafe and safe sport

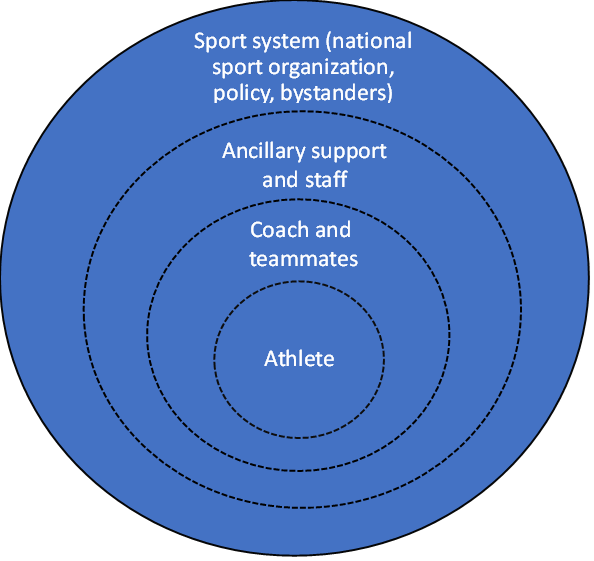

The athletes described slightly different contexts of unsafe and safe sport. In discussing when they feel safe in their sport, athletes focused on the environment closest to them, specifically their coaches, teammates and fellow athletes. They also referenced ancillary support and staff (for example, physiotherapy, nutrition and mental performance counselling, media support, financial aid). This connection to context is illustrated by the concentric circles that are closest to the athlete in Figure 1.

In contrast, in relating when they feel unsafe in their sport, athletes focused on a broader environment, including not only those closest to them (teammates, fellow athletes and coaches), but also ancillary support and staff and the sport system itself (notably their NSO, related policies and processes, and sport bystanders).

The athletes don’t particularly associate the sport system, including their NSO, with feeling safe in their sport (that focus was on the people closest to them). Instead, they described the system as the context of an unsafe culture.

As such, it isn’t surprising that athletes described a greater range of experiences of unsafe than safe sport. That suggests unsafe sport is a complex phenomenon.

What athletes have to say about feeling safe and unsafe in sport

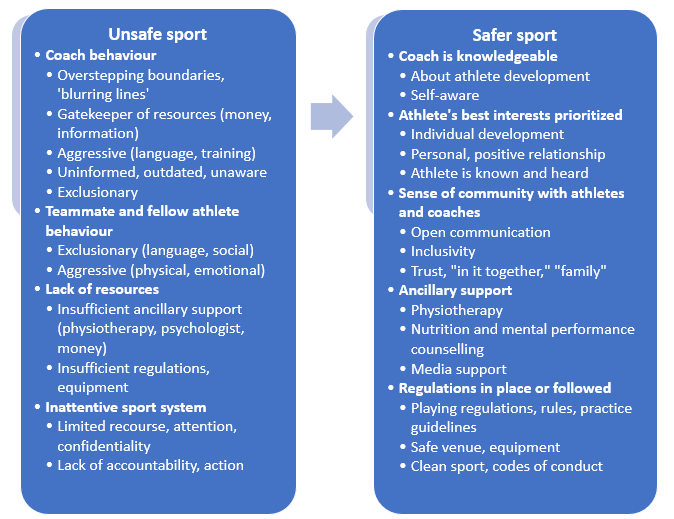

Athletes related specific experiences of “when I feel safe” and “when I feel unsafe” in their high performance sport environment. Figure 2 depicts the athletes’ experiences, and our interpretation of the necessary shift from an unsafe to a safer sport culture.

I feel unsafe when…

1. Coaches behave inappropriately

Unsafe coaching behaviour included overstepping boundaries and “blurring lines” by getting too involved in the athlete’s life (for example, nutrition, daily schedule, social world). One athlete stated:

“The coaches could be making comments about nutrition, looks, weight and that is a really big one in the sport. I’m sure there’s that kind of side of it, trying to kind of manipulate and change the way you do things, which often leads to eating disorders, especially in the sport that I’m in as well.”

Another athlete explained:

“It makes you not feel safe or respected or supported when a coach goes beyond, I guess, the lines of your performance and more so into your actual life, the decisions you’re making, your own autonomy.”

Athletes also feel unsafe when the coach is a gatekeeper of valuable resources, including financial support and information. Gatekeeping intensifies the power imbalance that already exists. Athletes also viewed as unsafe the coaches whose knowledge was out of date.

Athletes described aggressive and exclusionary coach behaviours as examples of when athletes feel unsafe in high performance sport. For example, one athlete said:

“Belittling you and attacking your character when you’re just asking a simple question.”

Another athlete referred to:

“That idea that your coach has his favourites, or your coach deliberately excludes you from drills or just somehow hinders your progress in any way, that makes sport an unsafe environment.”

2. Teammates and fellow athletes are exclusionary or aggressive

Athletes described teammates and fellow athletes as also exemplifying unsafe sport through exclusion. For example, through the language used in a group, and through exclusion from the group entirely. An athlete described:

“[Fellow athletes] trampling on people to get to the top and the people who, you know, don’t respect their training partners, people who don’t listen, who will belittle you or make you feel like you’re crap.”

Another athlete said:

“Teammates told me I wasn’t allowed to race in a club singlet [uniform] because I wasn’t in the group anymore.”

Athletes also described teammates and fellow athletes as contributing to an unsafe environment when they’re physically and emotionally aggressive:

“Putting other people at risk in [the sport] is unsafe. That’s like the biggest thing that I think of. So, like intentionally doing something to hurt someone else.”

3. There’s a lack of resources

Athletes positioned a lack of resources as an additional unsafe condition. They related insufficient ancillary support (for example, physiotherapy, mental performance, financial aid) as contributing to their vulnerability in the high performance environment. They also noted that common conditions of an unsafe environment included insufficient rules and regulations (or lack of regard for existing rules) both on and off the field of play, and unsuitable equipment and facilities.

Athletes shared examples such as:

“We didn’t have a team doctor at the time to help.”

4. The sport system is inattentive

Finally, athletes discussed the sport system in terms of a limited reporting process, where confidentiality isn’t protected, so individuals fear reaching out. Athletes also reported a lack of accountability and action. In those cases, the organizations didn’t necessarily check themselves when inappropriate behaviour exists. Or if such behaviour is acknowledged, the organizations took no action. For example, one athlete said:

“They kind of said, you can make a report, but you’re going to be [ostracized] for the rest of your career.”

Another athlete described:

“That is why I never approached anyone, and if I did, it would have been really weird to go about trying to get this [person] fired. But if they added up all the stories and they would have known something was very wrong, but there’s no in-between button. There’s no like yellow. It’s always like red, green, and it’s tough for the athletes. [Red meaning definitely inappropriate, reportable behaviour. Green is appropriate. Yellow is behaviour that either doesn’t fit clearly in red or green, or that athletes suspect the behaviour is inappropriate, but are unsure if it is.]”

These issues include the inaction of bystanders as well and the repercussions for athletes:

“I feel like it should be adults’ priority to step in when they see it happen and not depend or rely on a child basically, to come forward and say that it’s a problem. And if they see it with their own eyes, I think that they should come forward and stop it before things get out of hand. By the time they’re like 18, for example, it’s too late to step in at that point. But honestly, in my experience, [they] didn’t even step in. So then I think that’s really unfortunate, because it comes to the point where the athlete has to come forward, but after going through years of abuse, you get to the point where you’re brainwashed, and you almost don’t realize it’s abuse anymore.”

I feel safe when…

1. The coach is knowledgeable and prioritizes athletes’ interests

When discussing what constitutes a safe sport environment, the athletes also focused on coach behaviour. In particular, athletes feel safe when their coach is knowledgeable about athlete development and self-aware of their own strengths and limitations. In a safe environment, the coach has the athlete’s best interests in mind and is focused on their personal sport development through a positive, two-way relationship. An athlete described:

When discussing what constitutes a safe sport environment, the athletes also focused on coach behaviour. In particular, athletes feel safe when their coach is knowledgeable about athlete development and self-aware of their own strengths and limitations. In a safe environment, the coach has the athlete’s best interests in mind and is focused on their personal sport development through a positive, two-way relationship. An athlete described:

“Making sure you have a good environment around you; a good coaching staff. You’re developing in an appropriate way, relative to a long-term athletic development model. So, kind of safety as a broad term as in, you know, you’re developing in a proper way that’s going to allow you to have longevity in the career that you chose.”

2. There’s a sense of community

Athletes described a strong sense of community as fundamental to a safe sport environment. Inclusion, open communication, and trust among individuals who are like a family promotes emotional security. For example, an athlete said:

“Just supportive and there to help you without criticizing or judging your needs or anything like that.”

Another athlete described:

“You’re in an environment that you feel comfortable in. And when you’re pushing that boundary, that you have people around you [who] you trust. And then I would say a huge aspect of it is the emotional side of it and the cultural side of it. So being able to ask for extra help, being able to trust your teammates that they’re, they’re there for you.”

These were the most common manifestations of safe sport for athletes. However, athletes also noted support, such as the availability of physiotherapy, nutrition counselling and so on, and the existence and enforcement of regulations.

Toward a safer sport culture

There’s a need to shift away from the unsafe culture of high performance sport and its associated behaviours and practices described by the athletes in this study. In keeping with the athlete-centred focus of our study, we asked the athletes how the high-performance sport system in Canada could be a safer culture. They outlined several places to focus future attention, including elements of the sport system, coaching, teammates, and ancillary support and staff. The athletes most frequently outlined the sport system as a whole, and coach behaviour in particular, as targets for change.

There’s a need to shift away from the unsafe culture of high performance sport and its associated behaviours and practices described by the athletes in this study. In keeping with the athlete-centred focus of our study, we asked the athletes how the high-performance sport system in Canada could be a safer culture. They outlined several places to focus future attention, including elements of the sport system, coaching, teammates, and ancillary support and staff. The athletes most frequently outlined the sport system as a whole, and coach behaviour in particular, as targets for change.

Athletes’ targets for a safer sport culture:

- Sport system

- Creating and strengthening a culture of respect for athletes, and a sporting space that includes team-life balance

- Fostering and strengthening a sense of community (training group, NSO, on the field) that is athlete-focused

- Developing accountable systems for reporting unsafe sport

- Being aware and accountable when it comes to unsafe sport practices, athletes’ concerns must be heard

- Ensuring that third party reporting is independent of the organization

- Developing interactive, safe sport education that involves two-way communication and platforms to recognize progress

- Coaches

- Developing an understanding of athletes as people and having empathy for individual differences and development

- Strengthening the understanding that athletes need self-care to avoid injury and protect each other

- Participating in self-awareness and self-regulation training

- Teammates and fellow athletes

- Talking about what is safe and how to promote physical and mental wellness in the sport environment

- Creating an environment to learn from each other’s experiences

- Considering language used and how it can be offensive

- Support staff

- Being a part of the community that ensures rules are followed and violations are reported

- Providing media and communication training for athletes to be able to effectively express their voices

Canadian high performance athletes have shared their perceptions about unsafe and safe sport and provided insights to targets and mechanisms for change. Their voices must lead the way.

About the Author(s)

Eric MacIntosh, Ph.D., is a professor of sport management in the School of Human Kinetics at the University of Ottawa. His research interests include organizational culture, leadership, development and socialization. He is particularly interested in how leadership can form and shape organizational culture which can transmit positively internally and outwardly into the marketplace. Prof. MacIntosh has worked with many prominent national and international sport organizations (for example, Commonwealth Games Federation, Commonwealth Sport Canada, Right to Play). He is a co-author of Organizational Behavior in Sport.

Alison Doherty, Ph.D., is a professor of sport management in the School of Kinesiology at Western University, where she is also the Lead of the Sport and Social Impact Research Group (SSIRG). Prof. Doherty’s research focuses on safe and inclusive sport and physical activity. She is a member of Canadian Women & Sport’s Impact Research Committee, has coached with the Western Mustang Track & Field Team for over 30 years, and was a Canadian team member in the 1980s.

Shannon Kerwin, Ph.D., teaches and conducts research in the areas of organizational behaviour and human resource management (HRM) in the Department of Sport Management at Brock University. Kerwin’s research explores how personal and organizational values align to enhance important sport organizational outcomes and the influence of HRM practices on equitable outcomes within sport boards.

References

Alvesson, M., & Svenignsonn, S. (2016) Changing Organizational Culture: Cultural Change Work in Progress (2nd ed). Routledge, London

MacIntosh, E., Kinoshita, K., & Sotiriadou, P. (2020). Effects of the 2018 Commonwealth Games service environment on athlete satisfaction and performance: A transformative service research approach. Journal of Sport Management, 34(4), 316-328. DOI 10.1123/jsm.2019-0186

Johnson, J., Guerraro M., Holman, M., Chen, J.W., & Kroeker, M.A.S. (2018). An examination of hazing in Canadian intercollegiate sports. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 12, 144-159. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2016-0040

Kerr, R., & Kerr, G. (2019). Promoting athlete welfare: A proposal for an international surveillance system. Sport Management Review. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2019.05.005

Kerr, G., Willson, E., & Stirling, A. (2020). “It was the worst time to my life”: the effects of emotional abusive coaching on female Canadian National team athletes. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 28, 81-89. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2019-0054

MacIntosh, E. & Doherty, A. (2005). Leader intentions and employee perceptions of organizational culture in a private fitness corporation. European Sport Management Quarterly, 5, 1-22.

Parent, S., & Morel, M.P.V. (2021). Magnitude and risk factors for interpersonal violence experiences by Canadian teenagers in the sport context. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 45(6), 528-544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520973571

Schein, E. (2017). Organizational Culture and Leadership, 5th ed. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

The information presented in SIRC blogs and SIRCuit articles is accurate and reliable as of the date of publication. Developments that occur after the date of publication may impact the current accuracy of the information presented in a previously published blog or article.