Elaine Khoo, University of Toronto Scarborough

Xiangying Huo, University of Toronto Scarborough

Abstract

Multilingual learners whose dominant language is not English are often disadvantaged when their writing proficiency is judged against the Eurocentric standard English norm. Such deficiency models and deficit thinking devalue racially minoritized learners’ languages, leading to linguistic racism. A liberatory anti-racist, anti-oppressive, culturally responsive writing pedagogy was implemented at the Center for Teaching and Learning at a major university in Ontario, Canada. Eleven learners were analyzed in this one-month study. A mixed-method approach was used to analyze the impact of the implemented pedagogy based on several data sources, including learners’ reflective journal entries, transactional posts, and instructor feedback. The study shows the benefits of the writing pedagogy in helping learners improve their writing skills, agency, autonomy, voice, and critical thinking skills, as well as empowering them for emancipation and transformation. The study also reinforces the importance of practitioners’ shift from the provision of prescriptive and remedial feedback to personalized, learner-centered support by regarding learners’ languages and cultures as resources. Furthermore, de-emphasizing grammar while prioritizing critical thinking contributes toward dismantling the dominant monolith norm of standard English.

Keywords: deficit thinking, culturally responsive pedagogy, anti-racist, anti-oppressive, liberatory, writing pedagogy, writing centers, racially minoritized, empower, voice

Internationalization, immigration, and massification have increased cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic diversity of learners in higher education. Learners are disadvantaged if their dominant languages are not English and if they are culturally unfamiliar with the knowledge system valued in higher education that privileges Eurocentric, White, middle-class habitus (Sinclair, 2018). These learners are oppressed by a system that values standard English; their low proficiency in English positions them at a cognitive, affective, and sociocultural distance that is far from the White racial habitus.

The prevalent thinking about learners from diverse backgrounds views their challenges to be the result of endogenous deficits in the learners because of who they are when the learners enter higher education. The burden of supporting these learners has been borne by writing centers. This paper advocates that educators start to recognize that supporting our diverse learner body necessitates a collective awareness of how the pervasiveness of deficit thinking about learners from diverse backgrounds is intertwined with racism. This racism is “so deeply and invisibly enmeshed into thinking, interactions, systems, practices, and institutions, that disparities between Whites and people of colour are assumed part of a natural and inevitable order” (Anya, 2021, p. 1056). Acknowledging the seeming invisibility of the enmeshed racism in higher education, it is important to establish a risk-free, friendly, collaborative, cooperative, and inclusive space for racially minoritized learners to experience equal learning opportunities in higher education.

This article advocates increasing writing center’s support with a proactive liberatory pedagogy that enables learners to expand their English linguistic repertoire. This latter support enables learners to develop competence and confidence in communicating ideas in the ways that allow them to be their authentic selves. Hence, they are in better positions cognitively, affectively, and socioculturally to work on their assignments. This article presents how adding culturally responsive pedagogy as a nuanced overlay on the liberatory learner-driven and instructor-facilitated pedagogy supported learners with extremely low English language proficiency in developing their writing skills during a one-month timeframe.

Literature Review

Liberatory education, as introduced by Paulo Freire (2018) to help illiterate Brazilian farmers, is an inspiration for addressing the oppression that racially minoritized learners face in a banking approach to education rooted in colonial and neoliberal hierarchies that have dominated higher education (Dalmage & Martinez, 2020). The pervasive, unquestioned colonial domination has resulted in racially minoritized learners experiencing oppression in their academic environment, as the dominant languages they use is not the standard by which their work and their worth is measured. Since the neo-colonial oppression they face impacts how racially minoritized learners see themselves, their places in their academic environment, and their abilities to succeed against the odds—a starting point to address such oppression, is to recognize the underlying factors, such as assimilationist expectations contributing to racism, and to focus on improving the learning experiences of these Othered learners (Kumashiro, 2000). One way to combat imposed assimilation expectations and racism is to empower racially minoritized learners to develop their linguistic and affective resources to engage in the language of the oppressive system (Khoo & Huo, 2022b). Empowering learners to acquire the building blocks of language allows them to be liberated from constraints of having insufficient means to express themselves in their non-dominant language. Another generally overlooked advantage of this liberatory pedagogy is that it has bi-directional benefits for both instructors and learners. As Inoue (2015) noted, liberatory pedagogy brings bi-directional benefits in enabling educators to liberate themselves from “conventional assessment ecologies that keep (re) producing racism through the uncritical promotion of white racial habitus” (p. 84).

Deficit Models and Deficit Thinking

Deficit models of language proficiency result in racially minoritized learners being disadvantaged when their writing proficiency is judged against the hegemonic standard native speaker norm (MacKenzie, 2014). Mackenzie (2014) pointed out that “[w]ithin traditional EFL methodology there is an inbuilt ideological positioning of the learners as outsider and failure — however proficient they become” (p. 8). Such deficiency models discriminate multilingual learners and devalue their languages leading to linguicism (i.e., linguistic racism) (Holliday, 2005) which perpetuates inequality and negative stereotypes.

Deficit thinking presupposes learners who arrive from diverse background with limited English to be deficient, rather than acknowledges that academia is deeply entrenched in privileging Eurocentric values while being harshly unwelcome to other cultures, languages, and ways of knowing. Deficit thinking also ignores the fact that learners whose dominant language (e.g., those from East Asia and Middle East) in their linguistic systems very different from English face an additional “learning burden” (Nation, 2020, p. 24) when processing what they read and when trying to articulate their knowledge acquired through their mother tongues in English. Many learners need a longer processing time as they mentally try to decipher or translate what they encounter into their mother tongues to process the meaning. These challenges have resulted in their being negatively stereotyped as passive, dependent, and uncritical thinkers, unwilling to contribute in class (Robertson et al., 2000; Ruble & Zhang, 2013; Zhao & Bourne, 2011). Considering the huge disadvantages and challenges racially minoritized learners face with their writing assignments to be evaluated by Eurocentric standards of academic writing (Inoue, 2015), it is important to provide these learners with the opportunity to develop the language they need to express their authentic selves in their new environment. Without the opportunity for risk-free expression and for receiving caring, encouraging responses, racially minoritized learners are inequitably left todecipher how to comply with unfamiliar educational standards, expectations, and cultural systems.

Instead of perpetuating oppression in textual spaces (Sinclair, 2018), it is necessary to examine what it takes to create a non-oppressive experience for racially minoritized learners, which Leask (2006) advocates educators doing: “we must reflect on how we might change the way we think as well as the way we do things in response to the diverse needs of learners, rather than focusing primarily on how we can make them think and be more like us” (Leask, 2006, p. 189).

Writing Center Minimalist Tutoring Approach

The typical minimalist tutoring approach used in most North American writing centers is in fact an example of “literacy practices that reproduce the social order and regulate access” (Grimm, 1996, p. 5) since minimalist tutoring is based on Eurocentric middle-class values, such as hyper individualism (Inoue, 2016). When writing instructors are faced with tutoring learners from diverse backgrounds whose dominant languages are not English and who are unfamiliar with Eurocentric writing expectations, these instructors face a dilemma as to which areas to focus on within the consultation’s limited time (usually 30-50 minutes). Institutional denial of the language development needs of racially minoritized learners leaves the burden for supporting these learners to be shouldered by writing center instructors who apply the pedagogy of non-directedness in which they have been trained.

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy

Culturally responsive pedagogy emphasizes learners’ “cultural references” in every aspect of teaching and learning (Ladson-Billings, 1994). Gay (2010) pointed out that culturally responsive pedagogy is the “teaching to and through personal cultural strengths, intellectual capabilities, and their prior accomplishments” (p. 26) and that culturally responsive pedagogy challenges deficit models (Ladson-Billings, 2006) that treat multilingual learners as “underachieving” (Ladson-Billings, 2014).

Based on and developed from culturally relevant pedagogy, culturally responsive pedagogy includes three key principles: learner achievement, cultural competence, and critical/socio-political consciousness (by problematizing social inequity and injustice) (Ladson-Billings, 2021). In higher education, culturally responsive pedagogy upholds five key principles: “cultural consciousness, resources, moral responsibility, cultural bridging, and higher education curriculum” (Kilburn et al., 2019, p. 11). “Cultural consciousness” refers to anti-deficit awareness of learners’ cultures as assets (Gay, 2010). The word “resources” denotes the links between learning materials and learners’ own cultural backgrounds and knowledge (Kilburn et al., 2019). “Moral responsibility” entails teachers’ “understanding” and “empathy” (Jabbar & Hardaker, 2013, p. 278). “Cultural bridging” is to bridge the gaps between learners’ current and their previous cultural and academic knowledge (Kilburn et al., 2019). “Higher education curriculum” stresses learner-centeredness, diversity, and inclusivity to be reflected in the postsecondary curriculum (Jabbar & Hardaker, 2013). As a “bridge builder,” the culturally responsive instructor’s role is to provide multilingual learners with culturally oriented robust support essential to learners’ empowerment, transformation (Ahmed, 2019, p. 211), identity construction, and success (Golden, 2017).

In culturally responsive/relevant pedagogy, Ladson-Billings (1995, 2021) raised racialized learners’ sociopolitical awareness to problematize inequality in the mainstream society. However, Paris (2012) argued that the term “responsive”/“relevant” is not deep or explicit enough to address “the languages and literacies and other cultural practices of communities marginalized by systemic inequalities to ensure the valuing and maintenance of our multiethnic and multilingual society” (Paris, 2012, p. 93), cultural and linguistic pluralism (Paris, 2011) or stress “funds of knowledge” (Moll et al., 1992, p. 133) and repertoires of practice of multilingual and multicultural learners (Gutiérrez & Rogoff, 2003), or the third space (Gutiérrez, 2008; Gutiérrez et al., 1999) as what culturally sustaining pedagogy (CSP) has proposed and advocated. Expanded from culturally responsive pedagogy, culturally sustaining pedagogy dismantles Whiteness, interrogates systemic injustice, and “seeks to perpetuate and foster—to sustain—linguistic, literate, and cultural pluralism as part of the democratic project of schooling” (Paris, 2012, p. 95) as a critical, anti-racist, anti-colonial framework” to combat monolingualism, normalization, and hegemony (Alim et al., 2020, p. 262). Ladson-Billings (2014) clearly pointed out that “culturally sustaining pedagogy uses culturally relevant pedagogy as the place where the beat drops” (p. 76), showing the interactivity and continuity of culturally sustaining pedagogy developed and enriched based on culturally responsive/relevant pedagogy. This paper focuses on the implementation of culturally responsive pedagogy as a nuanced overlay on the liberatory learner-driven and instructor-facilitated pedagogy for minoritized learners in a Canadian higher education institution to improve their academic writing skills and liberate them.

Research Methodology

Downloaded data from learner engagement activities on the Canvas learning management system (LMS) were analyzed quantitatively and qualitatively.

Research Questions

- What is the impact of the implemented pedagogy in helping racially minoritized learners develop their academic writing skills?

- In what ways did the liberatory writing pedagogy empower and emancipate racially minoritized learners to articulate their thoughts?

Research Context

During the COVID-19 global pandemic, the regular eight-week Reading and Writing Excellence (RWE) co-curricular program at the Centre for Teaching and Learning at a large comprehensive university in Ontario, Canada, was pivoted to a fully online four-week program with the goal of supporting more learners in globally distributed locations. Two four-week cycles run per semester. At this university, the language development needs of learners were recognized as an important factor in supporting their academic access and success. Learners in this program read any of their own course readings for 40 minutes and immediately wrote their journal entries for 20 minutes daily to their instructor, summarizing their reading and providing their critical perspectives based on their reading materials. Details are described in other works: operational aspects (Khoo & Huo, 2022a) and impact on cohort (Khoo & Kang, 2022). Learners self-enrolled online to be in the program, and every learner was matched to an instructor.

Culturally Responsive Instructor

The instructor, also one of the two researchers/authors, is a bilingual assistant professor of writing at the Center for Teaching and Learning with a Ph.D. degree in Education, specializing in Language, Culture, and Teaching. This faculty has worked with numerous linguistically, racially, and ethnically diverse learners at five postsecondary writing or learning centers in Canada for over a decade and has considerable expertise in teaching learners interculturally and cross-culturally as well as conducted research in language ideology, anti-racism education, linguistic justice, writing pedagogy, ESL/EFL policies and practices, and higher education internationalization.

Participants

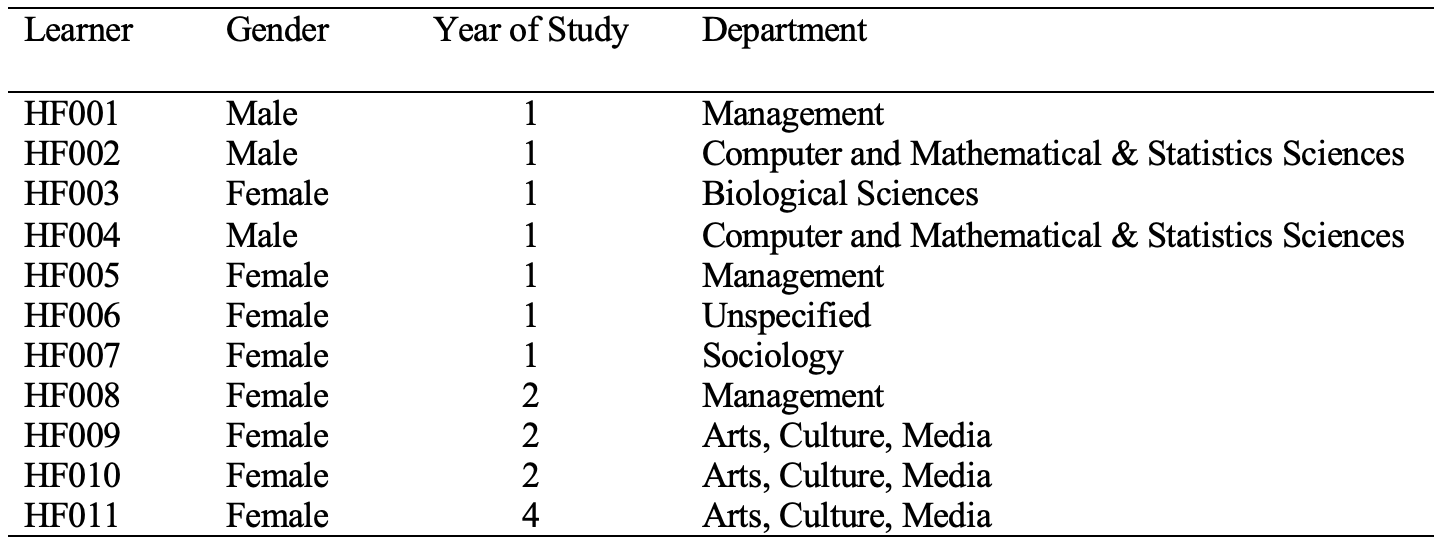

All participants in this study were from one group (among 8 groups) of the cohort of learners participating in this Reading and Writing Excellence program during the Fall 2020 semester. This group was of particular interest since all learners within this group had extremely low academic English language proficiency as measured by the Diagnostic English Language Needs Assessment (DELNA) screening test (Elder & von Randow, 2008) and thus were considered linguistically “at-risk” learners. These 11 learners, aged 20-30 years, consisted of 8 international and 3 domestic learners (see Table 1).

Data Collection

The Learning Management System (LMS) provides a rich source of learning analytics data about learner engagement that can contribute to making evidence-informed decisions about better ways to support the increasingly diverse learner population in higher education (Pelletier et al., 2021). The asynchronous communication in the LMS between learners and the instructor was examined using the following data: (a) journal entries and transactional entries; and (b) instructor responses to learners’ writing in their private discussion thread between each learner and their instructor over one month. Data for this group was extracted from the main dataset that had previously been downloaded and anonymized.

Learners’ Journal Entries

As the instructor did not read the actual reading done by the learners, the learners summarized the texts they read and shared their thoughts about the topics or aspects that they chose to write about. These reflective journals provided risk-free opportunities for learners to voice their thoughts.

Learners’ Transactional Entries

Transactional entries did not arise from learners’ prior reading. Instead, learners used these entries to explain why they were not able to write, sought clarification about their subsequent appointments, or shared their thoughts and feelings about something that was bothering them or they were excited about.

Instructor’s Responses to Learners

The instructor responses to each learner’s writing represent data points in this liberatory pedagogy that supports the anti-racist and anti-oppressive nature of learners’ writing.

Findings

RQ1. What is the impact of the implemented pedagogy in helping racially minorized learners develop their academic writing skills?

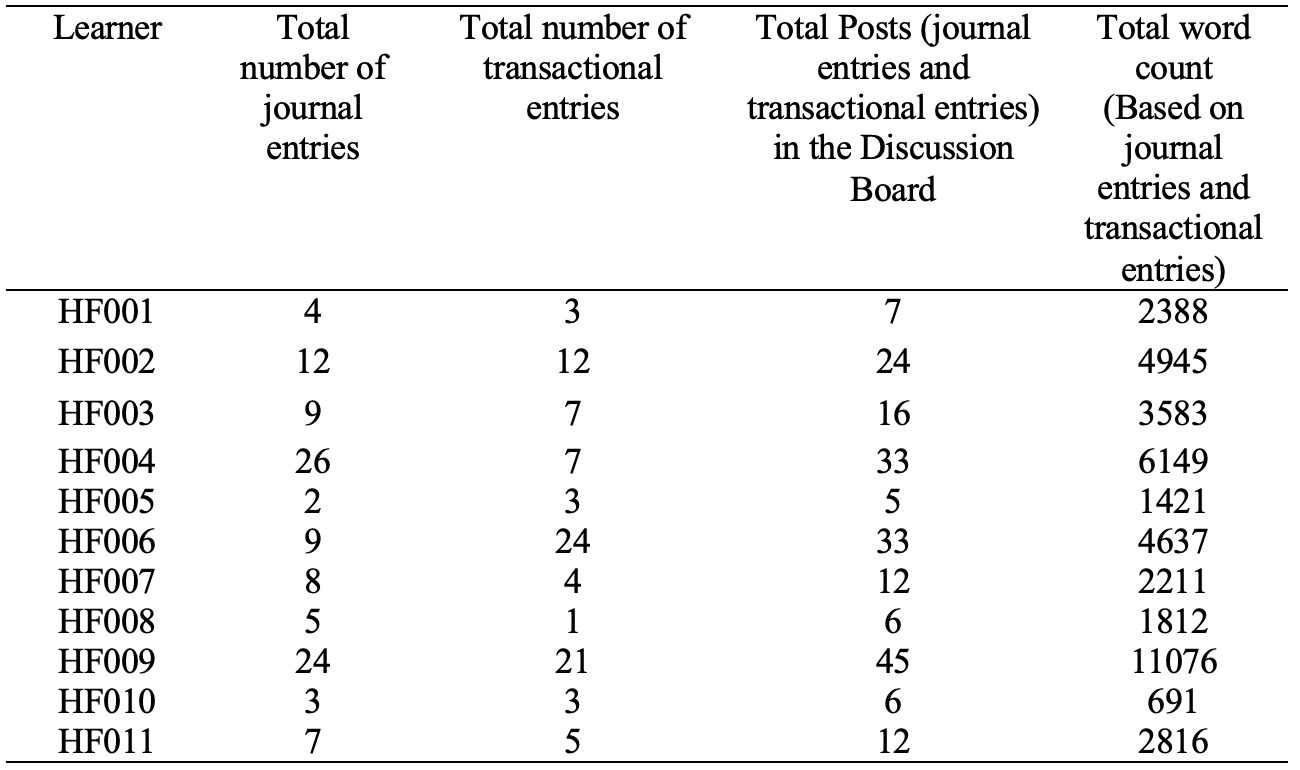

As learners had extremely low academic proficiency, any amount of engagement in English was a step forward in helping them improve written communication in their non-dominant language, particularly as they were living in their different home countries across the globe. Table 2 reflects a range of interactions where learners put in effort to communicate with their instructor. The level of engagement was seen by the total number of posts within one month. The word count of the learner (i.e., HF009) was 11, 076 words and 45 posts, much higher than the next two learners (i.e., HF004 and HF006) — 26 and 33 posts with the word count of 6,149 words and 4,637 words, respectively.

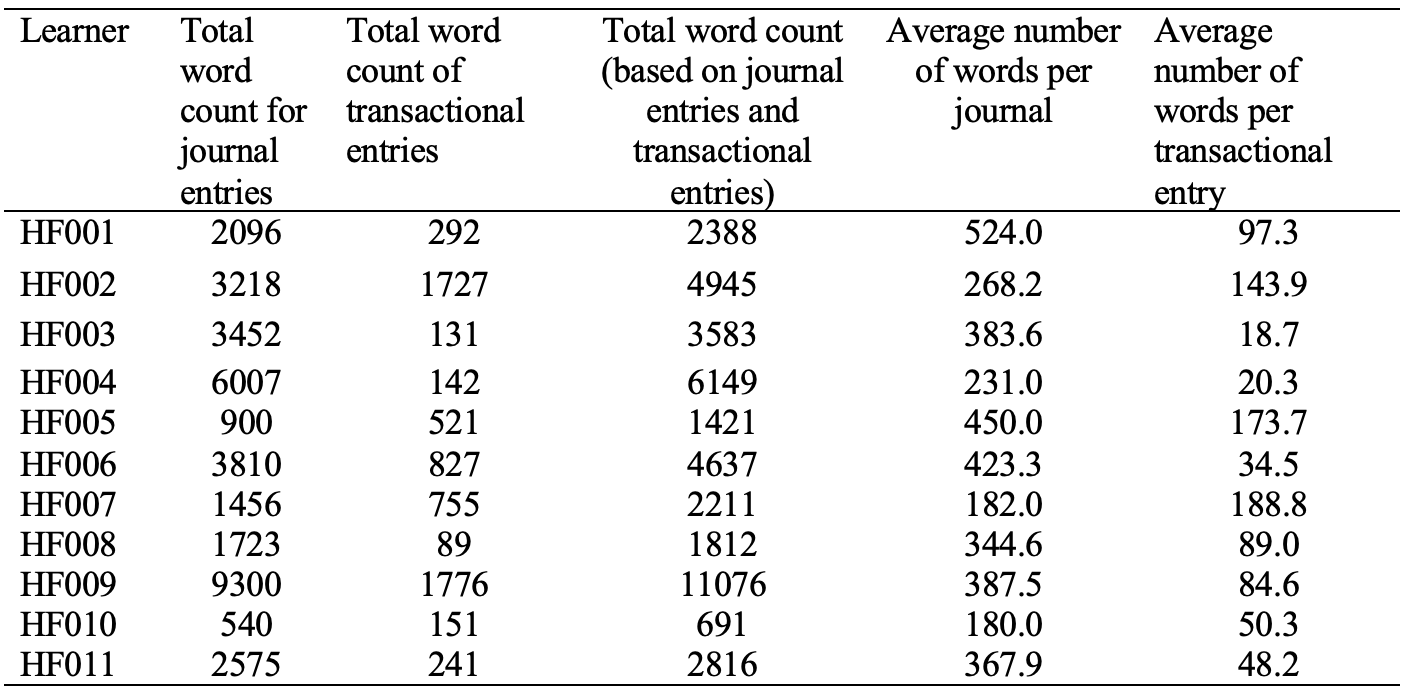

The liberatory nature of this pedagogy supports learners’ communication according to their specific needs. As they had a supportive reader—their instructor—they wrote many journal entries, as evidenced by 91% of these low proficiency learners writing over 1,000 words (Table 3). Only HF010 wrote under 1,000 words. In fact, HF002 and HF004 wrote 4,945 words and 6,149 words respectively. Some chose to communicate in transactional entries rather than journal entries (e.g., HF006). The general trend was a concentration on the journal entries.

From Table 3, the average number of words per journal entry provides an estimation of the number of words we could encourage low-proficiency learners to aim to write in their daily journals so that they could acquire the level of competence and confidence of language usage that would allow them to feel they could participate and have their voices. 72.7% of the learners wrote more than 250 words per journal and 27.3% wrote under 250 words per journal.

Transformation Related to Writing Skills

Qualitative analysis of the transactional entries showed learners’ perceptions of improvement in their academic writing with this high-impact writing pedagogy. These positive perceptions triangulate with the motivation to sustain their efforts at communicating their thoughts. Students’ quotes are presented in their original unedited versions.

Summarizing Skills

Since I joined this program, it has allowed me to develop a habit of summarizing what happened in life. After all, the non-repeatable journal makes me have to think about the content of writing every day. I tried to summarize the knowledge learned in class, and also shared some of the difficulties and joys I encountered in life. (HF002)

Academic Vocabulary

The vocabulary you suggested is very informative. I will definitely use them in my future writings.(HF009)

RQ2. In what ways did the liberatory writing pedagogy empower and emancipate racially minoritized learners to articulate their thoughts?

The capacity of the liberatory writing pedagogy to empower and emancipate learners is evidenced through the instructor’s decolonizing and anti-racist approach that emphasized culturally responsive pedagogy when responding to (a) learners’ journal entries and (b) learners’ transactional entries. This collaborative sustained effort values learners’ languages and cultures, maintaining learners’ strengths, ensuring their agency and voices, and constructing their multiple identities.

Decolonizing and Anti-racist Approaches Applied in the Writing Pedagogy

Thematic analysis of the culturally responsive instructor’s feedback brought out seven themes: customized feedback, motivating and encouraging, learner centeredness, critical thinking, cultural bridging, building dialogues as partners, and empathy and care.

Customized Feedback

The instructor’s responses to the learners were unique to each individual to meet every learner’s needs and interests. Learners were told to write in paragraphs instead of bullet points so that they could practice the writing skills useful to their assignments.

Motivation and Encouragement

Since trust and respect were pivotal to establishing the relationship between learners and the instructor in this voluntary program, the language used by the instructor was encouraging and thus motivated learners to feel safe to express their ideas. For example, the instructor wrote to one student (i.e., HF002): “I want to tell you how much I enjoy reading your journal(s) every time and how happy I am to witness/see your daily improvement and progress! You are doing a great job!”

Learner Centeredness

As learners with low academic English proficiency feel extremely vulnerable and powerless in a system that demands them to meet established Eurocentric standards, the pedagogy does the reverse. It centers on learners’ well-being, values learners’ time spent in their efforts, and builds their confidence to reflect on their reading materials.

I like your reflective questions always. In your last journal, your interesting question made me smile. You also raised a good question in this journal. If you think more and deeply about these questions and the article and offer more of your thoughts in depth and in detail (e.g., digging more and excavating the meaning and implications), that would be great!

Critical Thinking

To develop learners’ critical thinking skills, the instructor guided learners to think more profoundly about the texts, coupled with relevant and reflective questions.

I like both your summary and reflective parts. You have discussed “controlling variables” which is interesting…Besides the “controlling variables,” are there any other limitations? Are the research results reliable and valid? Any other suggestions on how to improve the reliability and validity of the research results? You may start to think about these questions to make your thoughts even deeper.

Cultural Bridging

Cultural bridging is to provide “cultural scaffolding” (Krasnof, 2016, p. 9) to fill the gaps between learners’ lives in their home countries and their new lives in the host society and build bridges between their former knowledge and the new knowledge that they are expected to acquire (Kilburn et al., 2019).

I guess maybe one of the reasons that you had so much to say in Journal 5 was because you discussed Chinese American’s novels and used the examples that you were familiar with (such as the stories/novels about Chinese history, society, and culture). In future, even if you are discussing a topic which is not so familiar to you, or is brand new, you could use examples in this way, do some research and use others’ findings and proofs (with citations always) to support your arguments.

Building Dialogues as Partners

Remember “putting all scholars in one room drinking coffee together” that I mentioned to you in our virtual meeting? If you could build dialogues or debates between those different scholars/researchers, your journals/essays will have multiple perspectives and will be more compelling.

Empathy and Care

Care in the culturally responsive approach is “action oriented…to ensure academic success for racially, ethnically, culturally, and linguistically diverse learners. Culturally responsive caring is a moral imperative, a social responsibility, and a pedagogical necessity” (Krasnof, 2016, p. 9). Empathy in this pedagogy is cultural empathy with humanistic and ethical support.

The instructor monitored each learner’s participation, engagement, and progress. After several days of noticing that a learner was quiet and inactive in writing, she reached out to the learner with the message below.

How are you? I have not heard from you since Monday, so I am writing to check whether everything is going well with you…Any concerns or questions about the program and my comments? I will be very happy to answer your questions and I am here to help you as your coach. I look forward to hearing from you and reading more of your journals very soon! Take care and stay safe and healthy!

For another learner struggling with mental health issues, the instructor expressed sympathy, empathy, active concern, and support to listen, understand, and care about the learner’s well-being. The learner accepted the instructor’s advice and received the timely professional support on campus using the links and the resources the instructor had provided. A culturally responsive instructor is compassionate and humanistic and avoids leaving the learner to struggle alone.

Learners’ Empowerment and Transformation

As learners were not limited to their assignment genre(s), they were set free to communicate their thoughts on their course readings as journal entries or in their personal communication as transactional entries. The categories below provide insights into their perceptions of empowerment and transformation.

Appreciation of Instructor Feedback

I am so glad to hear your precious feedback, I wrote down every word you said in my notebook! Your feedback is longer than my critical thinking journal, and I am very impressed. (HF006)

Reaction to Care and Active Concern

I am appreciated your concern about my mental issue. And provide me with this much support and help. It means a lot to me. I actually have talked to the therapist …this week, and try to do in-home work-out and reading to reduce my pressure and anxiety level. (HF001)

I just want to thank you, you let me feel I can have a friend in this university during this period. Thank you for your kindness! Thank you. (HF005)

The last learner’s excerpt revealed that the learner felt that the instructor was more like a “friend” at university rather than an authoritative figure who was unapproachable and inaccessible.

Learner Autonomy

With the implementation of this liberatory writing pedagogy, learners became active agents, taking initiatives in their reading and writing tasks as independent and capable readers and writers, as well as being ready to take future challenges.

Thank you for the suggestions and information. I hope that we can talk about the diversification of sentence structure in our (next) meeting. (HF003)

I am trying to spend some time to do a bit of research of my daily reading before I write now, so I can understand more from the reading itself. It indeed takes me more than 1 hour daily, but I think it is worth to do. I try to keep my reading + writing + research in 1.5 hours so that I am not losing interest in reading nor disturbing the regular study schedule for my courses. (HF009)

It seems that what learners have gained from the pedagogy is as follows: HF003 took the lead in the virtual meeting with the instructor and HF009 willingly invested extra time in research and reading by planning to allocate “1.5 hours” instead of the recommended one hour.

Agency and Transformation

Racially minoritized learners express their diverse academic voices in this risk-free, friendly, equitable, collaborative, cooperative, and inclusive space. Besides learners’ positive comments on the instructor’s personalized feedback, they also mentioned the support and encouragement that they had received boosted their confidence and helped them with their struggles. Thus, learner agency and voice are developed while learners’ identities are constructed. The anti-racist pedagogy enabled learners to achieve empowerment and transformation during their writing and learning process as expressed by one learner: “this success has given me a lot of confidence. I think as long as I conduct an effective review and preview based on your suggestions. I will do a great job.” (HF002).

Discussion

Reflecting on RQ1, the implemented pedagogy enabled learners to freely engage in written academic discussion with the instructor about their course topics. Only two students wrote far less than expected: HF010 wrote only 691 words while HF005 wrote 1,421 words. Others wrote 4,367—11,076 words, showing evidence to these learners themselves as well as to the institution that these racially minoritized learners have a wealth of ideas they can express about their course materials when conditions are conducive. Providing learners with a chance to develop their voices and confidence to assert their thoughts gave them a positive participatory experience. Learners understand that each new daily journal entry provides a fresh opportunity to share their thoughts and connect with the instructor in a non-hegemonic and non-hierarchical relationship about the course topics of their choice. This liberatory approach of helping racially minoritized learners gain competence and confidence resulted in their high level of engagement and collaboration. Also see the similar impact with a different cohort (Huo & Khoo, 2022).

Reflecting on RQ2, the liberatory writing pedagogy shows that by communicating through the instructor’s caring and collaborative approach, it successfully activated a strong response of active, empowered participation that led to learners’ improved abilities to develop their linguistic and affective resources which allowed them to have more equitable learning experiences.

Instead of continuing the common practice of leaving racially minoritized learners with low proficiency to be helpless beings in a system where they are negatively stereotyped as passive and deficient, demanding that they conform to the Eurocentric standards of academic writing, the liberatory writing pedagogy has illustrated that by creating an environment of non-judgmental, caring, compassionate, and interactional opportunities, it is possible to offer an alternative to the status quo of inequitable learning opportunities for racially minoritized learners. The status quo of unequal learning opportunities treats learners without sufficient levels of English as a burden that requires additional institutional resources to support, instead of acknowledging that these learners constitute valuable capital of diversity that can potentially benefit the learning community if they can be supported to overcome their initial culture and language-related barriers. In the case of international students who are being charged four to nine times higher tuition fees as compared with their domestic peers, the need for institutional accountability to provide effective ways of addressing this inequity is noted as “it borders on unethical to keep taking their tuition dollars and de facto promising they can succeed” (Murphy, 2022, p. 85).

As learners are free to withdraw from the program at any time, the sustained participation of most of the learners indicates the value of examining our commonplaces to include such personalized opportunities that respect diverse learners for who they are, without assigning them to remedial programs which offer generic support or assume writing center commonplaces can be a sufficient substitute for providing sustained personalized support to facilitate learners’ development of linguistic resources to assert their personhood in their new environment. Learners’ positive comments about the instructor’s support illustrate the power of the liberatory writing pedagogy in encouraging them to develop their voices through their reading and writing to share their perspectives. As confidentiality is assured and ideas are being responded to rather than language output being evaluated poorly, this model of positive interactions enabled the relationship of trust and risk-free exchange of ideas. Since learners need to operate in their non-dominant language, this emancipatory approach allows learners to develop competence and confidence in communicating with their course instructors in their non-dominant language. The encouraging tone of the instructor’s feedback, along with the instructor’s specific responses to learners’ unique questions and needs, has gained learners’ trust, as revealed by the nature of help seeking and vulnerability sharing in the transactional entries.

With the implementation of this impactful anti-racist, anti-oppressive writing pedagogy, the writing instructor has turned learners’ initial challenges into strengths. Learners’ dramatic achievements have changed how learners perceive themselves and their abilities to engage with university expectations for academic writing. The findings indicate the efficacy of the application of this emancipatory writing pedagogy. The pedagogy respects each learner by providing customized feedback, sustaining high motivation through constant encouragement, stressing learner centeredness, facilitating critical thinking, providing cultural bridging, building dialogues as partners, and showing empathy and care. In this way, the implemented pedagogy has empowered learners, met learners’ individual needs, and provided authentic meaning-focused and learner-centered responses to learners’ writing.

This paper argued for the recalibration of commonplaces so that there will be recognition of the need to provide personalized support for racially minoritized students that respects their diverse cultural, linguistic, educational, and socioeconomic backgrounds and empowers them to develop their linguistic resources for successful assertion of their personhood in their new academic environment.

Conclusion

With the implementation of this anti-racist, anti-oppressive writing pedagogy, learners’ dramatic achievements have changed how learners perceived themselves and their abilities to engage with university expectations of academic writing. The findings show the efficacy of the application of this emancipatory writing pedagogy in empowering learners, meeting their individual needs, and providing authentic meaning-focused and learner-centered responses to their writing. This proactive approach has not only motivated learners to write and improved their academic writing and critical thinking skills, but also has developed learner voice, identity, agency, self-autonomy, and diversity.

Limitations and Future Research

In future studies, interviews or focus groups will be included to learn more about the implementation and the impact of the writing pedagogy with the involvement of a larger sample of participants. Furthermore, to present a more comprehensive picture of racially minoritized learners with extremely low English language proficiency, more data is needed to compare learners’ retention, progress, and perceptions before and after the program.

Implications

Learners’ strengths need to be affirmed and appreciated. They bring various capital to the academic community with their access to knowledge through their languages, lived experiences in their cultures, as well as their previous academic success in their former education systems. Racially minoritized learners need a low-stake, risk-free, safe, equitable, and supportive space to express their ideas. Their empowerment and emancipation with the application of this liberatory anti-racist writing pedagogy have shown the necessity of creating such a space to ensure equity, justice, diversity, inclusion, and voice.

As the successful implementation of the anti-racist, anti-oppressive pedagogy largely rests on the shoulders of the instructors, teachers’ international and pluralistic lenses, passion, compassion, commitment, and dedication are indispensable to the teaching process. Teachers should make critical reflections on their own positions and teaching practices and become culturally responsive and interculturally competent by instilling the principles of inclusivity, diversity, and equity to combat hegemony (Huo, 2020) and teach for justice.

Author Biographies

Elaine Khoo, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor (Teaching Stream) at the University of Toronto Scarborough (UTSC). As the coordinator of the English Language Development (ELD) Support program, she has incorporated her research interests that include positive pedagogy in higher education, internationalization, technology-supported language learning, inclusive practices in academic integrity, language learning motivation, second language writing, and vocabulary studies into ELD programs to empower students to gain accelerated progress in academic reading, writing, and oral communication.

Xiangying Huo, Ph.D., is an assistant professor and writing specialist at the University of Toronto Scarborough. She has taught writing across the curriculum at the University of Toronto, York University, and OCAD Art and Design University. Her research interests include writing studies, anti-racist education, applied linguistics, ESL/EFL policy and pedagogy, internationalization in higher education, language ideology, and World Englishes. She is the author of Higher Education Internationalization and English Language Instruction: Intersectionality of Race and Language in Canadian Universities (2021, International Writing Centers Association Outstanding Book Award Finalist).

References

Ahmed, K. S. (2019). Being a “bridge builder”: A literacy teacher educator negotiates the divide between university-promoted culturally responsive pedagogy and district-mandated curriculum. Literacy Research and Instruction, 58(4), 211–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2019.1655683

Alim, H. S., Paris, D., & Wong, C. P. (2020). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A critical framework for centering communities. In N. S. Nasir, C. D. Lee, R. D. Pea & M. McKinney de Royston (Eds.), Handbook of the cultural foundations of learning (pp. 261–276). Routledge.

Anya, U. (2021). Critical race pedagogy for more effective and inclusive world language teaching. Applied Linguistics, 42(6), 1055–1069. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amab068

Dalmage, H. M., & Martinez, S. A. (2020). Location, location, location: Liberatory pedagogy in a university classroom. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 6(1), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649219883290

Elder, C., & von Randow, J. (2008). Exploring the utility of a web-based English language screening tool. Language Assessment Quarterly, 5(3), 173–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434300802229334

Freire, P., Macedo, D. P., & Shor, I. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.) (50th anniversary ed). Bloomsbury Academic.

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed). Teachers College.

Golden, N. A. (2017). “In a position I see myself in:” (Re)positioning identities and culturally-responsive pedagogies. Equity & Excellence in Education, 50, 355–367.

Grimm, N. (1996). The regulatory role of the writing center: Coming to terms with a loss of innocence. Writing Center Journal, 17(1), 5–29.

Gutiérrez, K. D. (2008). Developing a sociocritical literacy in the third space. Reading Research Quarterly, 43(2), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.43.2.3

Gutiérrez, K. D., Baquedano‐López, P., & Tejeda, C. (1999). Rethinking diversity: Hybridity and hybrid language practices in the third space. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 6(4), 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039909524733

Gutiérrez, K. D., & Rogoff, B. (2003). Cultural ways of learning: Individual traits or repertoires of practice. Educational Researcher, 32(5), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032005019

Holliday, A. (2005). The struggle to teach English as an international language. Oxford University Press.

Huo, X. Y. (2020). Higher education internationalization and English language instruction: Intersectionality of race and language in Canadian universities. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60599-5

Huo, X. Y., & Khoo, E. (2022). Effective teaching strategies for Chinese international students at a Canadian university: An online reading-writing support program. In C. Smith & G. Zhou (Eds.), Handbook of research on teaching strategies for culturally and linguistically diverse international students (pp. 241–264). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-8921-2.ch013

Inoue, A. (2015). Antiracist writing assessment ecologies: Teaching and assessing writing for a socially just future. The WAC Clearinghouse & Parlor Press.

Inoue, A. (2016). Afterword: Narratives that determine writers and social justice writing center work. Praxis: A Writing Center Journal, 14(1). http://www.praxisuwc.com/inoue-141

Jabbar, A., & Hardaker, G. (2013). The role of culturally responsive teaching for supporting ethnic diversity in British university business schools. Teaching in Higher Education, 18(3), 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2012.725221

Khoo, E., & Huo, X. Y. (2022a). The efficacy of culturally responsive pedagogy for low-proficiency international students in online teaching and learning: A Canadian experience with an online reading-writing program. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 16(2), 67–85. https://doi.org/10.22329/jtl.v16i2.7022

Khoo, E., & Huo, X. Y. (2022b). Toward transformative inclusivity through learner-driven and instructor-facilitated writing support: An innovative approach to empowering English language learners. Discourse and Writing/Rédactologie, 32, 394–404. https://doi.org/10.31468/dwr.963

Khoo, E., & Kang, S. (2022). Proactive learner empowerment: Towards a transformative academic integrity approach for English language learners. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 18(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-022-00111-2

Kilburn, M., Radu, B. M., & Henckell, M. (2019). Conceptual and theoretical frameworks for CRT pedagogy. In L. Kyei-Blankson, J. Blankson & E. Ntuli (Eds.), Care and culturally responsive pedagogy in online settings (pp. 1–21). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7802-4

Krasnof, B. (2016). Culturally responsive teaching: A guide to evidence-based practices for teaching all students equitably. Region X Equity Assistance Center at Education Northwest.

Kumashiro, K. (2000). Toward a theory of anti-oppressive education. Review of Educational Research, 70(1).

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children (1st ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

Ladson-Billings, G. (2006). It’s not the culture of poverty, It’s the poverty of culture: The problem with teacher education. Anthropology Education Quarterly, 37(2), 104–109. https://doi.org/10.1525/aeq.2006.37.2.104

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: A.k.a. the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74–84. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.84.1.p2rj131485484751

Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). I’m here for the hard re-set: Post pandemic pedagogy to preserve our culture. Equity & Excellence in Education, 54(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2020.1863883

Leask, B. (2006). Plagiarism, cultural diversity and metaphor—Implications for academic staff development. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 31(2), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930500262486

MacKenzie, I. (2014). English as a lingua franca: Theorizing and teaching English. Routledge.

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & Gonzalez, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching: Using a qualitative approach to connect homes and classrooms. Theory Into Practice, 31(2), 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849209543534

Murphy, G. A. (2022). Bringing language diversity into integrity research—What, why, and how. Journal of College and Character, 23(1), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2021.2017974

Nation, P. (2020). The different aspects of vocabulary knowledge. In S. A. Webb (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of vocabulary studies (pp. 15–29). Routledge.

Paris, D. (2011). Language across difference: Ethnicity, communication, and youth identities in changing urban schools. Cambridge University Press.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X12441244

Pelletier, K., Brown, M., Brooks, D. C., McCormack, M., Reeves, J., Arbino, N., Bozkurt, A., Crawford, S., Czerniewicz, L., Gibson, R., Linder, K., Mason, J., & Mondelli, V. (2021). 2021 EDUCAUSE horizon report: Teaching and learning edition. EDUCAUSE.

Robertson, M., Line, M., Jones, S., & Thomas, S. (2000). International students, learning environments and perceptions: A case study using the Delphi technique. Higher Education Research and Development, 19(1), 89–102. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07294360050020499

Ruble, R. A., & Zhang, Y. B. (2013). Stereotypes of Chinese international students held by Americans. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 37(2), 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2012.12.004

Sinclair, M. (2018). Decolonizing ELA. The English Journal, 107(6), 89–94.

Zhao, T., & Bourne, J. (2011). Intercultural adaptation—It is a two-way process: Examples from a British MBA program. In L. Jin & M. Cortazzi (Eds.), Researching Chinese learners (pp. 250–273). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230299481