Brazil’s post-pandemic recovery threatened by inflation and rising rates

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Brazil’s post-pandemic economic recovery threatens to slow sharply next year as economists sound the alarm over surging inflation and interest rates as well as the effect of an unprecedented drought.

Buoyed by policies that largely kept businesses open during the Covid-19 crisis, Latin America’s largest economy bounced back to pre-pandemic levels in the first quarter of 2021 and looks set to end the year with more than 5 per cent annual growth.

Second-quarter data, released on Wednesday, showed that the economy shrank by 0.1 per cent from the previous quarter, having grown 12.4 per cent from the same period last year.

The outlook for next year, however, is growing increasingly bleak, with analysts now beginning to revise down annual growth estimates to as low as between 1 and 2 per cent. In addition to concerns over rising prices and interest rates, many fear political volatility in the run-up to next year’s presidential election. There is also concern that the government may imperil its fiscal position by handing out cash in the form of new social welfare programmes.

“Going forward, the economy will be jammed by a triple whammy. The first one is inflation. It will definitely undermine consumer purchasing power. The second is the consequence of inflation — the central bank is now rushing to deal with [interest rate increases]. In order to fight inflation, we will have to hurt the economy,” said Marcelo Fonseca, chief economist at asset manager Opportunity Total.

“The third is the uncertainty. The fiscal regime is in danger and I don’t think that outlook will change during the electoral period. There will be a lot of turbulence, so some slowdown in investments, which have been driving the recovery, is inevitable.”

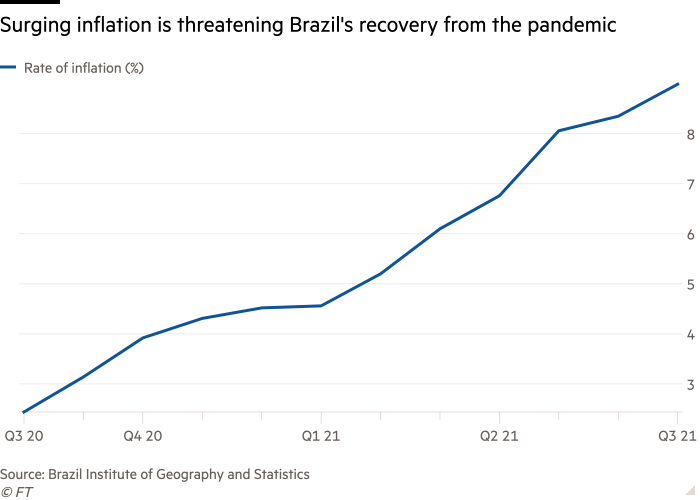

Inflation has historically haunted many Latin American nations and its sudden return this year in Brazil has spooked policymakers, who are now rushing to control prices.

In the 12 months to July, inflation stood at 8.99 per cent, well above the 2021 target of 3.75 per cent. In response, the central bank has lifted its benchmark Selic interest rate from an all-time low of 2 per cent to 5.25 per cent. Market expectations are that it will reach 7.5 per cent by the end of the year. This would further weigh on economic activity.

Complicating the picture further, unemployment is high at more than 14 per cent, meaning consumption remains stunted.

“Inflation is already lost for this year — the effort now is to control it for next year,” said André Braz, an economist at the Brazilian Institute of Economics.

“Brazil is a very unequal country and inflation for poorer people is higher than for rich people because poorer people spend more of their income to buy food — and the price of food has increased more than other categories,” he added.

Alongside food, the price of electricity has also soared as the effect of the worst drought in almost 100 years takes its toll.

Brazil relies on hydroelectricity for 65 per cent of its energy generation, but with reservoirs in the centre and centre-west of the country now almost dry, the government has become increasingly concerned about power outages, which would hammer the real economy.

“We’ve never seen a drought like this — it looks like I’m being tested. I appeal to you at home now: turn off a light. This way you will help save energy and water from the hydroelectric dams,” president Jair Bolsonaro said last week.

Fonseca at Opportunity Total added: “Be it preventive power rationing or simply frequent blackouts, the point is that this is a major tail risk to growth over the next quarters.”

Economists are also on edge ahead of a presidential election campaign next year, which threatens to bring a pronounced bout of political volatility. Trailing in the polls, Bolsonaro has in recent weeks lashed out at Brazil’s democratic institutions, raising the spectre of a coup and spooking international investors in the emerging market.

“Concerns with regards to political stability have become much more worrying. Until now we’ve been shrugging it off as part of the [show]. But this is not children’s play. Maybe they do mean harm,” said Paulo Bilyk, chief executive of Rio Bravo Investimentos.

Analysts also fear the government may abandon its commitment to fiscal rectitude ahead of the polls in order to win votes with cash handouts.

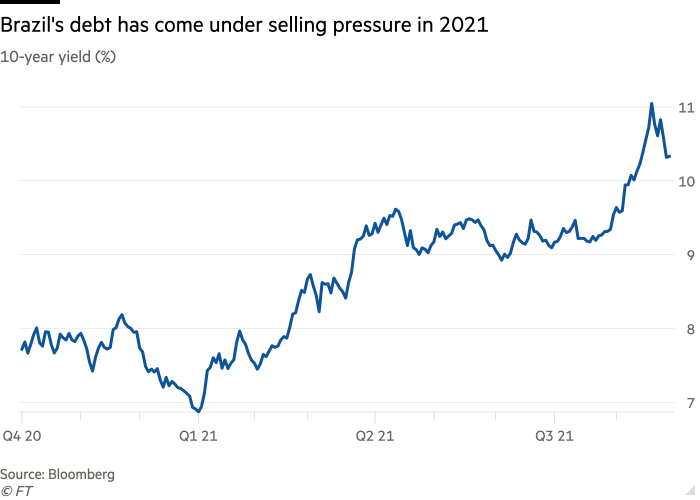

At 84 per cent of gross domestic product, Brazil’s public debt remains high for a developing economy.

Investors have until now remained sanguine about the risks, mostly thanks to a mandated spending cap that keeps government expenses fixed in line with inflation. If that cap was abandoned, however, many predict an exodus from Brazilian assets and deep economic turbulence.

“The economic team is clearly struggling to come up with a solution to satisfy fiscal constraints and the demands of politicians. As we get closer to the election, the risk is that politics will prevail,” said Viktor Szabo, investment director at Aberdeen Standard Investments.

“Brazil could easily get back on an unsustainable debt trajectory. It has quite a high level of debt with quite short maturity — you don’t want to mess with such a situation. The debt can easily explode.”

Comments