Nobel Prize-winning physics professor follows her gut

“I have tremendous confidence in myself. . . I just go and do what I want to do.”

“I have tremendous confidence in myself. . . I just go and do what I want to do.”

By Beth Gallagher University RelationsDonna Strickland joined the ranks of Marie Curie this week, becoming the third woman in history to win the Nobel Prize in Physics. But the Waterloo professor admits she’s not one for deep reflections on her long career.

She quite simply loves fundamental science.

“I have always just done what I’ve wanted to do,” says Strickland, an associate professor in Waterloo’s Department of Physics and Astronomy. “People ask about being a woman and I don’t even think I noticed it throughout my career.”

Strickland, who helped revolutionize laser physics, shares half the $1.4 million Nobel Prize with French laser physicist Gérard Mourou. Together they paved the way toward the shortest and most intense laser pulses created by humankind. Strickland conducted this Nobel-winning research while a PhD student under Mourou in 1989 at the University of Rochester in New York. The team’s research has a number of applications today in industry and medicine — everything from laser eye surgery to laser printers.

Strickland remembers the thrill of capturing their invention — known as Chirped Pulse Amplification (CPA) — on camera. “You do know when you are seeing something for the first time,” she says. “It was exciting.”

Strickland’s career as a physicist took her around North America. After getting an undergraduate degree at McMaster University in Hamilton, ON., Strickland applied to graduate programs at the two top schools in North America for optics and the study of light. She accepted the offer at Rochester after being turned down at the other top school. Once on campus, a fellow Canadian graduate student invited her to check out Mourou’s laser lab.

“We walked into the lab and it was full of these red and green lasers. I just said, ‘Oh my God. It’s like working around a Christmas tree all the time. How fabulous is that?’ “It was just sort of a gut reaction.”

During the early part of her career, she was conducting research in a highly competitive discipline at a time when conferences on ultra-fast lasers drew only 200 people around the world. After graduating with a PhD in 1989, Strickland said she had a hard time finding work in New Jersey where she wanted to live. She moved around and eventually took a job on the technical staff of Princeton University’s Advanced Technology Center for Photonics and Opto-electronic Materials.

At the time, she was told it was risky to leave the academic track for a technician’s job but Strickland wanted to be near her husband who worked at Bell Labs and to start a family. “A lot of people tell women you shouldn’t have babies but I say, ‘Just do it when you want to do it and things will work out. Just keep going forward.’ ”

Four years later, Strickland, who grew up in Guelph,ON., got a job at the University of Waterloo. Her husband followed her back to Canada where she now leads an ultrafast laser group that develops high-intensity laser systems for nonlinear optics investigations.

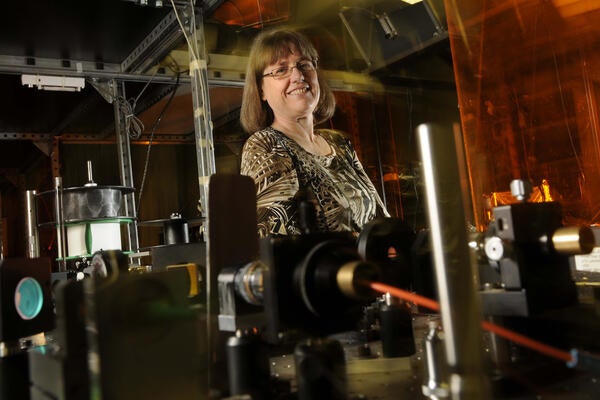

Professor Strickland wearing laser goggles in a 2011 photo.

She is just as passionate about fundamental science today, as she was on that day back in the 1980s when she first saw the invention that would one day win her a Nobel Prize. Strickland acknowledges the good that the CPA has spawned in the world, but says for her it is curiosity that drives her to discover more.

“People have to realize that to go from the pure to the final takes a lot of effort but if we don’t have people doing the front-end research eventually you run out of things to work on. . . in 50 years, we’ll run out of ideas.”

Strickland credits her father who was an electrical engineer and her mother who had wanted to study math and science but instead went to university for arts, as the reason she has always had the confidence to follow her passion. Strickland has a daughter who is studying astronomy at the University of Toronto and a son who is studying comedy at Humber College.

At a press conference on Tuesday, Strickland told young people to choose a career that is fun to them. She said: “The world works best if we all do what we’re good at…Did I ever think I should be out there helping humanity?” she asked “No. I just think if we do what we’re really good at it helps the world.”

Watch the full press conference.

Read more

Donna Strickland becomes the first Canadian woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics

Read more

Professor Donna Strickland says breakthrough work on chirped pulse amplification (CPA) was fun

Read more

Donna Strickland wins Nobel Prize for groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics. She is the first woman to win the physics prize since 1963

The University of Waterloo acknowledges that much of our work takes place on the traditional territory of the Neutral, Anishinaabeg and Haudenosaunee peoples. Our main campus is situated on the Haldimand Tract, the land granted to the Six Nations that includes six miles on each side of the Grand River. Our active work toward reconciliation takes place across our campuses through research, learning, teaching, and community building, and is co-ordinated within the Office of Indigenous Relations.