Indexing During the 2010s

Index funds delivered as promised.

The Active/Passive Barometer Last Friday's column assumed its premise, that index funds comprehensively bested the average actively managed fund during the past decade. Several readers wished to hear more. What evidence supports such a broad conclusion? Enter the Active/Passive Barometer, authored by Morningstar's Ben Johnson. The Barometer's latest edition evaluates fund performance through December 2019, thereby permitting a complete view of the preceding decade.

The Barometer differs from other studies by creating its passive benchmarks from funds, not indexes. Typically, calculations of active versus passive performance compare active funds against theoretical benchmarks. This decision is acceptable for back-of-the-envelope efforts, but as those benchmarks bear no costs, it places active funds at a disadvantage. The Barometer's approach levels the playing field.

The Barometer also treats active funds relatively generously by equally averaging the totals of all passive funds within a Morningstar Category rather than either selecting the largest passive fund or asset-weighting the results. In general, using the latter two calculations would lead to higher passive returns, as the bigger passive funds typically have lower expense ratios than the norm and thus better performances.

Tough Odds First, let's look at active funds' 10-year success rates. The Barometer defines success as finishing the time period while outgaining the category's passive-fund average. In contrast, funds that were liquidated or merged out of existence, or funds that survive but post lower returns than the passive-fund average, are coded as failures. Success rates of greater than 50% show that the odds favored those who selected actively managed funds, while rates of less than 50% indicate otherwise.

(A technical note, for those interested in such matters. The universe consists of both mutual funds and exchange-traded funds, and the Barometer's definition of passive is loose rather than strict, meaning that the report classifies any mechanically derived fund as passive, even if that portfolio does not weight its holdings according to market cap.)

The Barometer evaluates 20 categories. For simplicity's sake, I cut that number in half, selecting the report's 10 largest categories, as measured by assets. (As you may verify by downloading the Barometer, pruning the list does not change the basic story.) Their 10-year success rates appear below, with active-fund success rates of greater than 50% highlighted in green.

Ouch! Only diversified emerging markets surpassed the 50% barrier, and just barely at that. In five of the 10 categories, actively run funds did not even reach the 20% mark. While it's true that investors don't buy funds at random, and can improve their chances through research, finding winners while selecting from a bin that contains more than four failures for every success is an exceedingly daunting task. Even Warren Buffett doesn't get it right 80% of the time.

Objection, Your Honor Objection 1: The report doesn't consider risk Properly speaking, the Barometer should measure risk-adjusted returns rather than returns alone. However, risk-adjusted performance is difficult to present. Who can name an appealing Sharpe ratio? Also, it seems peculiar to deem an active fund that trails its index-fund competitors as having been "successful."

The argument would nonetheless be compelling if active funds were riskier than passive funds. But they are not. Some bond index funds are more volatile than their actively run competitors, owing to their longer durations and (ironically) higher credit qualities, but most U.S. stock index funds are relatively stable. Their improved diversification compensates for the fact that they are fully invested.

Objection 2: The success rate ignores the amount of under- or outperformance If the failing active funds fell just short of matching passive funds' returns, while the successful active funds greatly outperformed their targets, then judging category performances by their success-rate percentage would be a mistake. Using that single summary figure would obscure vital information.

Anticipating this possibility, the Barometer provides the distribution of active funds' excess returns for each category. The upshot: Large-company U.S. stock funds remain woeful, but the results for other categories improve. In many cases, the mode of the distribution (that is, the most common outcome) is positive.

However, there is a catch: This analysis can be generated only on funds that continue to exist. For example, the mode is +1 percentage point for foreign large-blend funds. That certainly is good. Yet of all the foreign large-blend funds that entered January 2010, only 61% survived through December 2019. The other 39% were terminated, most likely while performing poorly.

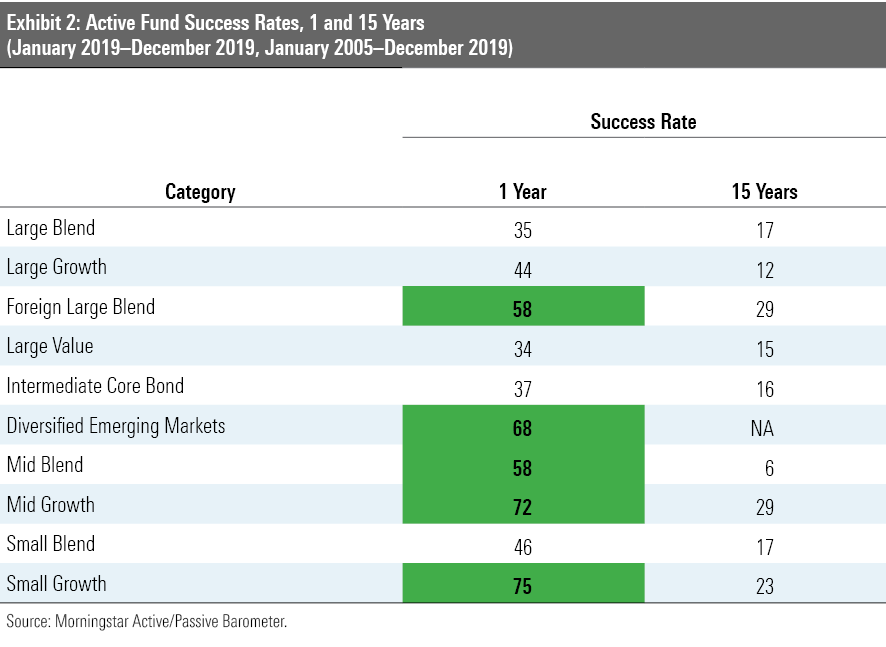

Objection 3: What about different time periods? Fair enough. Let's see how actively run funds fared for the trailing one- and 15-year periods.

Active funds look much better in the recent past! In contrast, aside from large-company U.S. stock funds, their 15-year results are even worse than their 10-year totals. Viewed in isolation, one could interpret this pattern as indicating that active management has long faced headwinds but now enjoys better conditions.

That could be. But the simpler and more likely explanation is Jack Bogle's claim: Over the short term, costlier funds can compete effectively with their low-cost rivals, thanks to market fluctuations. But the longer the time period, the less likely that expensive funds will overcome their expense-ratio handicap.

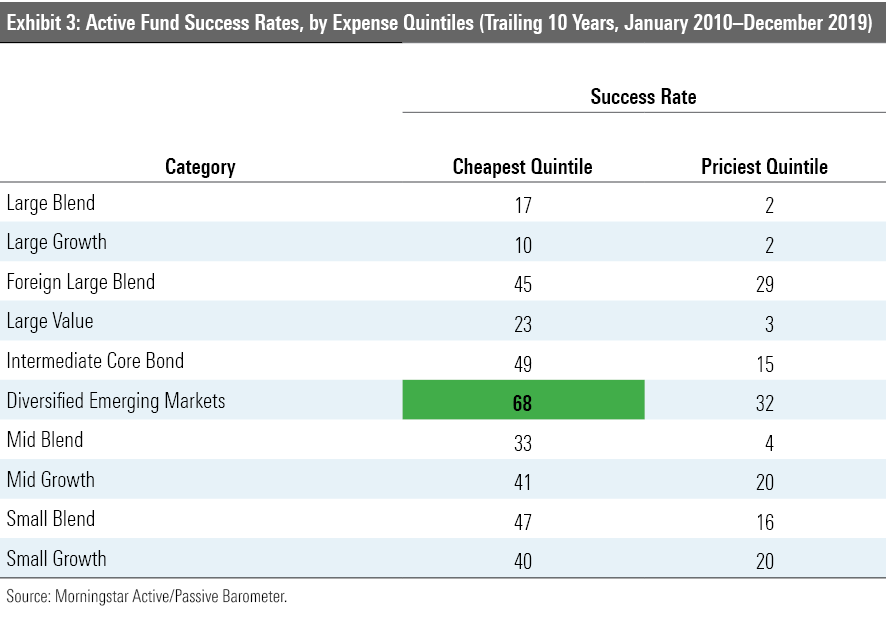

Objection 4: If you eliminate the dogs, active management does fine The same might be said of the passive-fund averages. Nevertheless, the counsel is sound, assuming that the dogs can be identified in advance. The most reliable approach is to screen on costs. Once again, the Barometer provides the answer, as it sorts active funds by their expense ratios. The most expensive 20% qualify as the priciest quintile, while the thriftiest 20% land in the cheapest quintile.

Without question, the expensive funds perform wretchedly. Removing them certainly does improve active funds' percentages. However, even the cheapest active funds weren't quite able to keep pace with the passive-fund averages. They narrowed the gap, particularly outside of their trouble spot of the U.S. large-company equity categories, but they didn't close it. Once again, only the single category of diversified emerging markets stocks bested the 50% mark.

Wrapping Up Index funds entered the 2010s at record popularity. Never had they been so praised, nor attracted so many investor dollars. But they did not fly too close to the sun. Despite the occasional dire warning--they grew more numerous as the decade progressed--index funds continued to meet investor expectations, by gradually accumulating small advantages, across a wide variety of asset classes.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-25-2024/t_d30270f760794625a1e74b94c0d352af_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DOXM5RLEKJHX5B6OIEWSUMX6X4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)