Dermacentor variabilis: American dog tick

Dermacentor variabalis is a large reddish-brown to gray-brown tick. In Canada, D. variabilis is found from eastern Saskatchewan and east through to Nova Scotia, primarily in the southern portions of each province.

Summary

Dermacentor variabilis, the American dog tick, is a large, reddish-brown, ornate hard tick. In Canada, it is found from Alberta east to Nova Scotia, and has increasingly pushed west and north in the last decades. Dermacentor variabilis is a three-host-tick with each stage of the life cycle (larvae, nymphs and adults) feeding on a separate host. Domestic animals acquire this infestation when habitat is shared with free-ranging hosts, for example grazing by livestock or hiking with dogs in wilderness or urban green spaces. Dermacentor variabilis is seasonal in its activity with adults (the life stage primarily seen on domestic animals) actively questing for hosts in spring and early summer. Adult ticks prefer larger mammals including wild ungulates, domestic livestock, dogs and people. Dogs, horses and cattle with light to moderate infestations generally do not display any clinical signs. Hair loss may be seen in heavy infestations. Depending on the owner’s risk tolerance, there are 3 tiers to tick control on pets; the first is simply to avoid tick habitat, especially in the spring and early summer. The second is to do thorough tick checks and remove ticks from pets within 6-24 hours of being active in tick habitat. The third tier involves administration of topical or oral tick preventatives, which serve as repellents or systemic products that rapidly kill ticks within hours of infestation. Systemic isoxazolines are rapidly becoming the treatment of choice for tick prevention in dogs and cats, while older repellent type products (i.e. imidacloprid with permethrin, and some other pyrethrin/pyrethroid-based products) may still be used in dogs, but are unsafe for cats. Dermacentor variabilis will readily feed on people. This tick is known to transmit the causative agents of Ehrlichia canis, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, and tularaemia, although only rarely in western Canada.

Taxonomy

Subphylum: Chelicerata

Class: Arachnida

Subclass: Acaria

Order: Ixodida (Metastigmata)

Family: Ixodidae

As arachnids, ticks are closely related to mites and spiders. Other hard ticks of veterinary importance in Canada include Rhipicephalus sanguineus, Dermacentor andersoni, D. albipictus, and various Ixodes spp. including I. scapularis and I. pacificus, the vectors of Borrelia burgdorferi - the cause of Lyme disease.

Note: Our understanding of the taxonomy of helminth, arthropod, and particularly protozoan parasites is constantly evolving. The taxonomy described in wcvmlearnaboutparasites is based on Deplazes et al. eds. Parasitology in Veterinary Medicine, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2016

Morphology

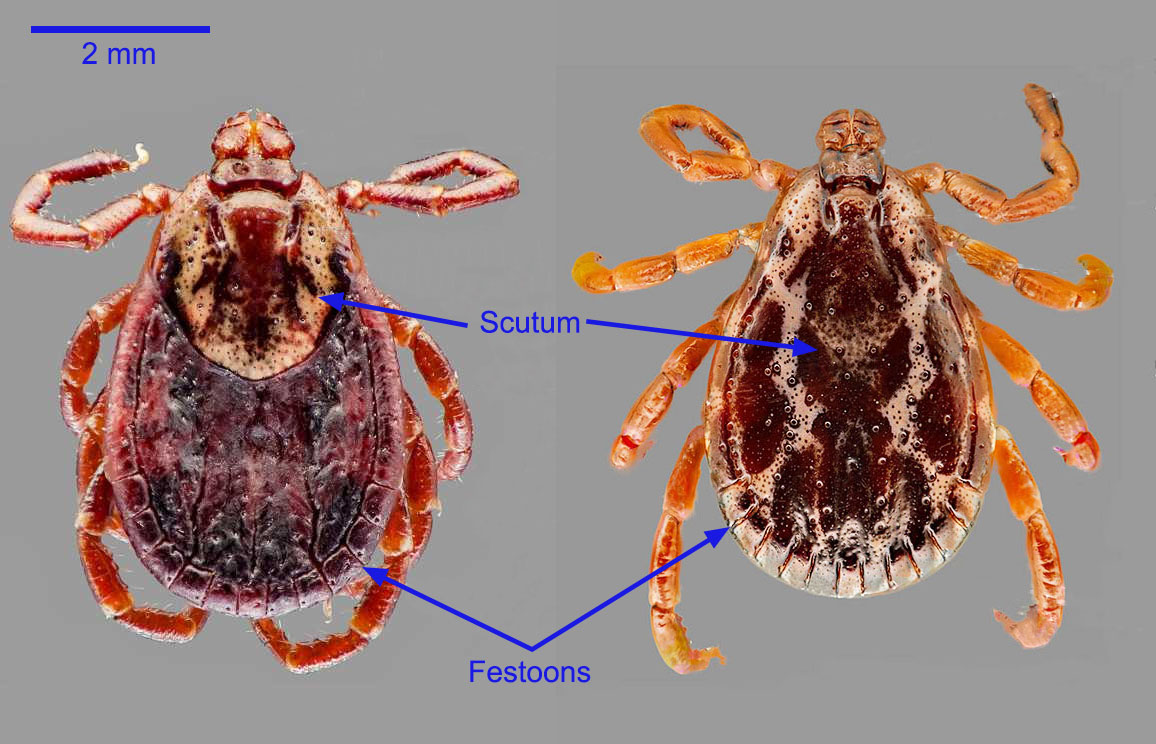

Dermacentor variabilis is a large (unfed adult females are 5-7 mm long, fed females can be double in size) reddish-brown to gray-brown tick. All life stages are dorsoventrally flattened. The larvae have six legs while the nymphs and adults have eight legs. Dermacentor variabilis is an ornate tick (white colouring on the scutum), has festoons, distinctive eyes on the scutum, and the basis capituli (at the base of the hypostome) is rectangular. Species of Dermacentor can be differentiated by the shape of the spiracle located ventro-laterally behind the last pair of legs, and the size and number of goblet cells in the spiracle.

Host range and geographic distribution

Life cycle

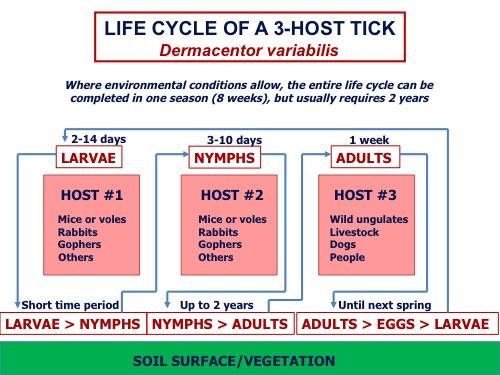

Dermacentor variabilis is a three-host-tick with each stage of the life cycle (larvae, nymphs and adults) feeding on a separate host. The life cycle of D. variabilis follows a basic pattern but there can be great variation in the timing of the cycle across its broad geographic range.

Adult D. variabilis overwinter off the hosts and begin to emerge from hibernation (exit diapause) in early spring (April through May depending on the location within the tick’s geographic range) and actively search (quest) for hosts by climbing to the tips of grass blades and other low vegetation waiting for appropriate hosts to brush past. Numerous mammal species can serve as hosts for adult D. variabilis. They are generally larger animals, primarily dogs but also deer, elk, coyotes, horses, cattle, sheep and people. As the weather warms, the ticks become active in greater numbers, reaching a peak of activity in the late spring (mid May to late June). As days get hotter and drier, the number of active ticks declines rapidly, although some ticks will remain active all summer. Most adult ticks that have not found hosts by mid-summer seek protection under ground debris and generally will not become active again the following spring. These unfed ticks can survive for at least two years and possibly longer, and become active each spring. Adult ticks that have been successful in finding a host will feed for about a week, mate during that time, and drop off the host into the environment. Females lay eggs about seven days later and then die.

Eggs hatch approximately a month after being produced. Although a small percentage of D. variabilis larvae will begin to actively quest shortly after hatching, the majority of these newly hatched larvae will settle into the ground debris until the following spring (May and early June) at which time they will actively seek hosts, generally small mammals, primarily mice and voles. If successful in finding a host they will feed for 2-14 days and fall off into the environment where they moult and become nymphs.

Most nymphs of D. variabilis begin questing shortly after moulting. They will search for small mammal hosts, almost exclusively mice and voles and, if successful, feed for between 3 and 10 days. They fall off the host and moult to the adult stage. D. variabilis nymphs can be found from March to October across their North American geographic range, with peak numbers seen in June. In general, newly emerged adults generally do not feed until the following spring.

The entire life cycle can occur in one season (54 days under ideal laboratory conditions) but it is generally completed in two years. Factors that influence life cycle completion include temperature, humidity and host availability. Conditions supportive of tick development can advance the timing of the cycle and increase tick abundance. With continued climate change, earlier, warmer springs may lead to adult ticks questing earlier in the year, but this may be countered by hotter summers and regional variation in precipitation.

Epidemiology

Dermacentor variabilis is seasonal in its activity with adults (the life stage primarily seen on domestic animals) actively questing for hosts in spring and early summer. Climatic factors such as temperature, wind and moisture levels will affect tick activity. Dermacentor spp. ticks are most active on sunny, windless days in warm spring or moderate summer temperatures. They tend to be found on tall grass or low brush, along the edges of trails, pastures, and wooded areas with deeper litter for environmental stages. While ticks tend to be associated with rural and wilderness regions, they are increasingly found in urban green spaces (river valleys, parks, off leash areas, etc).

Pathology and clinical signs

Dermacentor variabilis transmits the causal agents of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF) (Rickettsia rickettsii) tularaemia (Francisella tularensis), and canine monocytic ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia canis). These pathogens are believed to be extremely rare in dogs in Canada, although RMSF and canine ehrlichiosis are of concern in dogs in the United States and Mexico. Dermacentor variabilis (along with Amblyomma americanum) is also a vector for cytoauxzoonosis (Cytauxzoon felis), which does not occur in Canada. In cattle, D. variabilis is a vector for Anaplasma marginale.

Diagnosis

Owners may observe engorged ticks on their livestock or pets. Dermacentor spp. ticks are quite large and easily recognizized by white markings on the scutum, and by their posterior festoons (scalloped edges). Dermacentor variabilis is, however, similar in appearance to the other Dermacentor species found in Canada and is differentiated by its seasonal occurrence, geographic location and by the size and shape of the goblet cells within the spiracle plates. These are located ventro-laterally behind the last pair of legs.

Most veterinary personnel should be able to identify ticks to genus level, but owners in western Canada can also seek identification by submitting digital photos of ticks through the eTick App or website (https://www.etick.ca/) or to their provincial surveillance program. Some owners may want the tick or their pet tested for exposure to pathogens, and PCR screening panels are increasingly available for these purposes. Results should be interpreted carefully, since ticks may test positive for pathogens present in blood recently taken from a host, but this does not mean that they are competent to transmit the pathogen.

Treatment and control

Depending on the owner’s risk tolerance, there are 3 tiers to tick control on pets; the first is simply avoiding tick habitat, especially in spring and early summer. The second is to do thorough tick checks and remove ticks from pets within 6-24 hours of being active in tick habitat. This timing is based on the minimum amount of time for ticks to attach, feed, and transmit pathogens. Ticks can be carefully removed with tweezers (or fingers) by grasping the mouth parts as close to the skin as possible (ticks secrete a glue patch and embed their mouthparts deep into the skin, so use slow and steady pressure). Bites should be washed and monitored for signs of local bacterial infection.

The third tier involves administration of topical or oral tick preventatives, which serve as repellents or systemic products that rapidly kill ticks within hours of infestation. Systemic isoxazolines are rapidly becoming the treatment of choice for tick prevention in dogs and cats, while older repellent type products (i.e. imidacloprid with permethrin, and some pyrethrin/pyrethroid-based products) may still be used in dogs, but are unsafe for cats.