In Amazonia, the Inga people are creating a decolonial biocultural university

Education and writing have always been powerful means through which reality is invented, designed and constructed. In the case of the Andean highlands and the lush Amazonian forests of southern Colombia, inhabited by various Indigenous peoples, these fundamental devices of colonial power were introduced by Catholic missionaries. The journeys of the missionaries were not only aimed at evangelising and educating; they also had the function of exploring and conquering. Education was understood as a major driver for pacifying communities and moulding them to suit the values of the conquerors, as well as drawing the Indigenous population into locating and exploiting natural resources such as minerals, gold and rubber.

The colonisation of this region has continued over the last few decades with armed and social conflict, the war on drugs, expropriations, oil extraction and militarisation. But in this scenario, Indigenous communities are not passive subjects. A strategy to resist the advance of colonisation is to recover their own cultural knowledge and to engage in intercultural dialogue.

Higher education in Colombia is traditionally clustered in the urban power centres in the Andes, representing a considerable obstacle for poor rural populations. Those Indigenous students who do complete their degree in universities in Medellín, Cali or Bogotá often do not return to their community, not least because the education they receive fails to meet the demands of a prosperous life in the Indigenous territories. This continuous drain of young educated people leads to a population that lacks the skills required to thrive culturally, socially and economically.

In 2019, students from ETH Zürich and Javeriana University in Bogotá visited the Inga territory in Colombia and considered the possible spatial manifestations of an Indigenous university. The notion of a ‘campus’ was reimagined as a constellation of sites across Inga territories and the nearby city of Villagarzón

Credit: Studio Anne Lacaton / ETH Zürich

Given all these violent encroachments on their ways of life and territories, the Inga people of Colombia who live in the country’s south-west undertook what they call an atun iachai ñambi (great path of knowledge) to conceptualise, design and build an Indigenous university, meeting their own needs and cosmovisions based on the Andean philosophy of suma kausai (good living), in deep connection with the Earth and all its beings. With the fragile process of pacification, following the Colombian peace agreement of 2016, came a desire to reconnect and build on a collective vision for the future, which includes permanent structures for higher education. They strive for a university that will safeguard their cultural knowledge, language and natural environment, and prepare the community for a professional future in their territories to contribute to suma kausai.

Colombia’s Indigenous peoples, of which there are currently more than 115 recognised by the state, represent a surprisingly rich cultural diversity. However, the educational proposals offered to these peoples are not in line with this diversity. Their often difficult humanitarian situation, as a consequence of armed and social conflict, has led them to defend political autonomy, territorial autonomy and cultural autonomy as part of a strategy to guarantee their survival over time. For the Inga people, educational autonomy is part and parcel of this strategy.

As a result of a broad process of grassroots participation, the Inga proposed Proyecto Educativo Propio (Our Own Education Project) through a document named Chasam Munanchi Puringapa Nukanchi Iachaikuanawa (This is how we walk with our knowledge) published in 2009. Their project addresses the questions: what kind of people do we want to be? What kind of Inga do we want to educate? How can education help us protect our culture and territory? To answer these questions, the Inga have organised their educational project around learning environments that bring into dialogue Indigenous and western knowledge, while placing the world-making capacity of oral discourse and caring practices at the core of the learning experience.

‘Decision making is a complex collective process in the Indigenous context that requires a lot of care for the project to succeed’

This journey led to the creation of an educational model which lays the foundations for imagining and planning in three central categories: thinking, feeling and doing. They do not simply want to have a university: they want to co-create one. The Inga people have made the decision not only to enjoy an educational offer to which they certainly have a right as citizens; they have also created an educational proposal that is relevant, stimulating and generates new possibilities for them. Their educational project is ultimately a political project and a life project. To think about education is to think about life, about what is alive and about the concrete and profound ways in which we can become across time and space.

In 2018, at the invitation of the Inga leader Hernando Chindoy, we – an interdisciplinary group of researchers, pedagogues, architects and artists – began a creative collaborative process, supporting the Inga Education Team and other Inga political and social units in advancing and communicating this biocultural project. Bringing our multifaceted backgrounds into dialogue with Indigenous ways of doing research and creating knowledge, this future institution is bound to be pluri epistemic. We engage in numerous conversations with Inga leaders, healers, elders and traditional medics, hold shared workshops in the field, do field trips together into remote parts of the territory, socialise the ‘university’ concept among the dispersed Inga communities across the region, and participate in the official meetings of the Inga authorities to obtain their approval. Decision making is a complex collective process in the Indigenous context that requires a lot of care for the project to succeed.

The Inga concept of curricula comprises five interrelated learning routes: territorial governance, environment and ecology, sustainable economies, Inga medicine, and language and communication. In Indigenous pedagogical methodologies, learning is not abstract and text-based but unfolds through practical activities across sites such as the chagra (biodiverse horticultural gardens), the tulpa (the fireplace), minga (communal work), assemblies, community meetings, rituals, long walks in the forest, spatial design and a range of artistic expressions.

‘An ecological community in the forest is not a network of pre-existing interconnected points, but a mesh of life‑pathways in which we are fully embedded’

Inga spirituality, traditional medicine, and ceremonies are of central importance in guiding the paths of learning, which for the Inga are not just paths of investigation and knowledge generation, but of affection, solidarity, wisdom and pursuit of harmony among the multiplicity of beings and life forms that co-exist in the territory. The biocultural university proposes the co‑creation of a decentralised learning experience that integrates not only human communities, but also plants, rivers and other beings, as living cognitive subjects within the educational agenda. The scope of the project is not limited to a specific Indigenous community; rather it hopes to drive the broader paradigm shift from an extractive to a more generative relationship with the territory.

In the Andean-Amazonian Indigenous context, despite the violence of colonisation, the understanding that humans are an integral and equal part of all life systems has enjoyed a long-uninterrupted history, from which we have much to learn. The Inga biocultural university is an expression of a mode of learning, teaching and co-creating knowledge that involves other-than-human beings as sentient and cognitive entities comprising a living territory. Unlike the idea that knowledge creation is an act of human attribution of meaning to an external and agentless world, for the Inga the world can be known when other-than-human beings are considered subjects or actors. The sun, the sacred vine, the jaguar, the hummingbird and other forest beings are members of a cosmological community of sentient and cognitive selves. An ecological community in the forest is not a network of pre-existing interconnected points in a space external to us, but a mesh of life‑pathways in which we are fully embedded, in an incessant co‑emergence, movement, change and decay with other beings. Meandering rivers, growing plants, human and non-human animals, and even language, are all life‑pathways or trajectories of movement forming a living territorial fabric.

A relational form of teaching and learning that recognises other-than-human beings as subjects with whom we co-emerge is part of a decolonial pedagogy to counteract the accumulated harmful social, economic, environmental and epistemic impacts of the Catholic schooling in the Andean Amazon. A decolonial pedagogy, such as the Inga’s, offers important lessons for learning and teaching, as it problematises an anthropocentric view of the world that renders non-modern experiences as ‘cultural beliefs’ of ‘local peoples’. A case in point is the use of psychoactive plants in the context of schools. In contrast to the increasingly popular ingestion of ayahuasca in the west for the purpose of self-search or ‘exotic’ entertainment, in the Amazonian context the plant is vital to how knowledge is experienced and transmitted: it is Indigenous science.

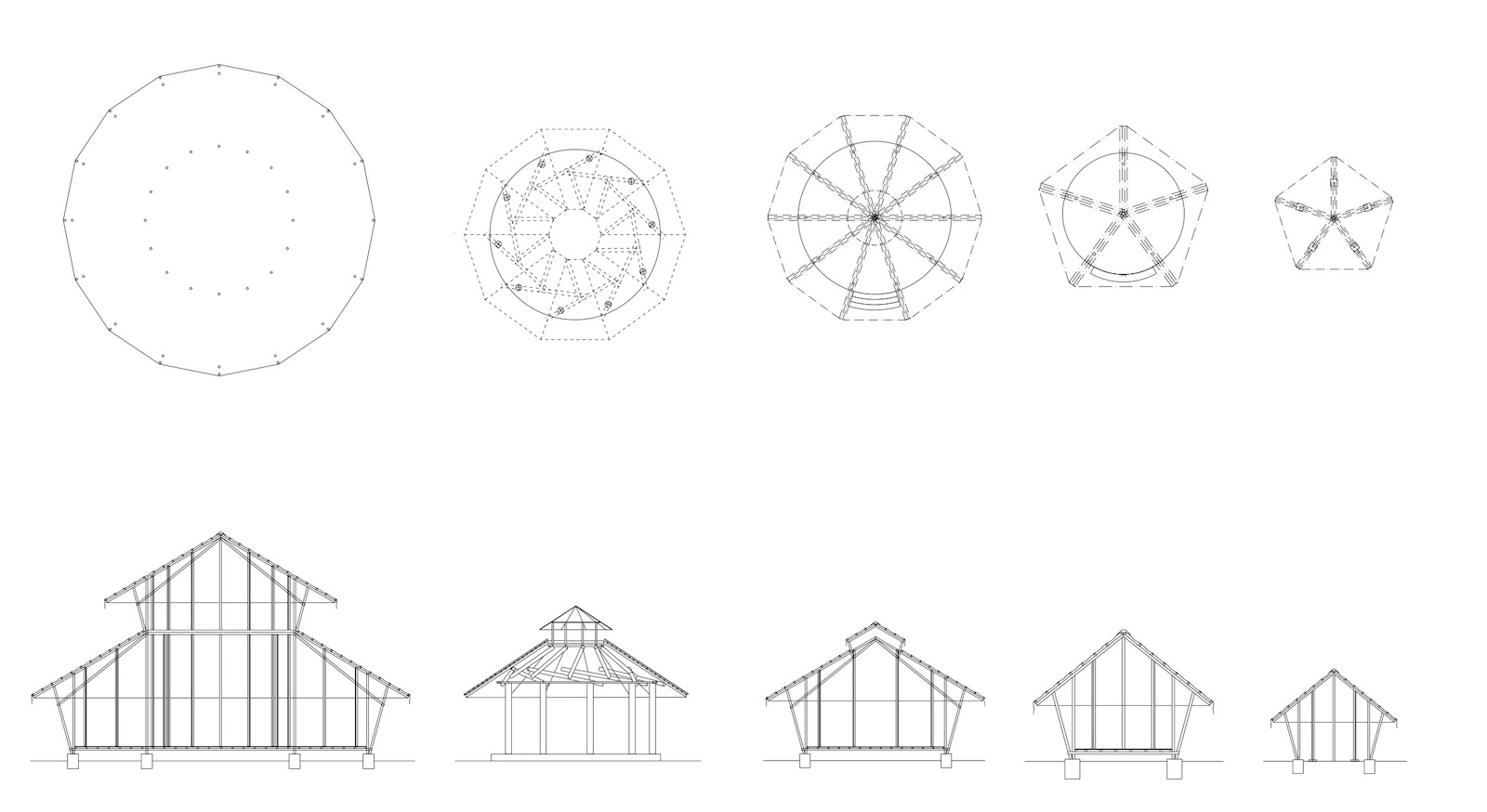

At the building scale, structures are informed by Indigenous typologies and technologies, constructed from materials collected locally

Credit: Studio Anne Lacaton / ETH Zürich

The university’s spatial design is conceived at various scales, simultaneously engaging territory and architecture to facilitate Indigenous learning pathways. The idea of a traditional ‘academic campus’ is questioned and rethought as a decentralised network of sites spreading across all Inga jurisdictions, corresponding to the idea of territory as a knowledge-producing subject. Páramos (high moors) and villages in the Andean mountains are interwoven with rainforests and riparian communities in the Amazonian lowlands as a meshwork of knowledge sites. Iaku (rivers) and ñan (roads) that bring these landscapes together are not considered merely routes but learning spaces in themselves. This network also reconnects sacred places that have been fragmented by centuries of colonialism and decades of armed conflict. Conceptually and physically, buildings and landscape interventions will weave together Inga territory through a series of tulpa iuiai (spaces for thought) that are suitable for particular types of learning; river-learning, forest-learning and language-learning all take place in different spatial conditions.

The construction of infrastructure across Inga territory will not require enormous investments but a high degree of creativity about how to take advantage of existing buildings. Spaces for learning and doing can be attached to active schools or communal spaces, thus lowering the barrier to the integration of students and their families with intercultural higher education. In this sense, the university does not only play an academic role but becomes a platform for the community to overcome a violent past still in need of reconciliation.

At the architectural scale, design and building are being led by a team of Inga construction experts, collaborating with architects and engineers from Colombia and abroad. Minga is the method that guides this process, the ancestral Indigenous practice that calls upon the community to work collectively towards a common goal. This form of co-operation is also a moment to share food, stories and music, where people of all ages meet to celebrate what is being achieved and to strengthen relations of reciprocity. A first building is already planned for the site of El Tambor in Piamonte, Cauca. This will be a highly symbolic space that aims to be a contemporary-built expression to symbolise a centuries-old knowledge system.

‘As much of the ancestral knowledge is in peril of extinction, audiovisual productions will be an important resource for future generations of students’

Buildings in every location will be organised according to the natural and spiritual logics established by mamas and taitas (community knowledge holders). Footpaths connect buildings to the surrounding landscapes and to special locations for the sacred ambiwaska ceremonies. Construction materials will mostly come from each site. In this sense, the university will be ‘planted’ beforehand by guaranteeing the sustainable provision of wood and bamboo through agroecological plots: spaces that will also provide the university with healthy, locally grown food and medicinal plants. This approach nurtures design’s potential for ecological transition, and it channels relational modes of knowing, being and doing into the creation of a ‘pluriversity’, where communities learn in mutually enhancing ways with each other and the Earth.

Imagination, image-making, design and art are considered central ingredients in making the project a reality, which we call Devenir Universidad (becoming university). Art is deployed as a constant companion and mediator in this inter‑epistemic co‑operation. As much of the ancestral knowledge is in peril of extinction, audiovisual productions – such as the creation of a sound and video archive of the territorial history and Inga thought on education, culture and persistence in the territory – will be an important resource for future generations of students. Devenir Universidad is a collaborative network, an artistic initiative and online platform, and various publications and exhibitions that communicate the project among Indigenous communities and international audiences. It is a common place where visions for the future university can be shared and developed before they begin to materialise in curricula, architectures and various forms of productions in the territory.

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design