1 Introduction

In migration studies, domestic courts are traditionally theorised as ‘a source of expansiveness toward immigrants in liberal states’ (Joppke, Reference Joppke1998) contrary to legislatures influenced by the negative public opinion towards immigration. In their explanations, with a primary focus on Europe and North America, migration researchers emphasised ‘the relative insulation of courts from electoral politics’ as conducive to the expansion of foreigners’ rights (Guiraudon, Reference Guiraudon, Bommes and Geddes2000). They argued that as courts gain more influence over immigration and asylum policies, national governments face constraints in implementing restrictive measures due to the rise of rights-based politics (Hollifield et al., Reference Hollifield, Hunt and Tichenor2008). While Joppke (Reference Joppke1998) had clarified that this argument may not be universally applicable to all liberal democratic states, this strand of scholarship broadly stresses ‘the transformative role of judicial agency in the fight for the extension of human rights protections’ for migrants (Basok and Carasco, Reference Basok and Carasco2010).

While some migration scholars traditionally view the judiciary as playing a positive role in protecting migrants’ rights, currently there is a lack of agreement on the extent to which judges effectively contribute to the advancement of these rights. First, legal scholars and practitioners have expressed scepticism regarding the courts’ ability to curtail the authority of national governments in controlling immigration and in protecting human rights (Sackville, Reference Sackville2000; Legomsky, Reference Legomsky2000; Rehaag, Reference Rehaag2012; Motomura, Reference Motomura2010). Second, recent migration scholarship questioned the earlier assumption that ‘the judiciary possesses an inner logic that strives for inclusive immigration policies’ (Johannesson, Reference Johannesson2018). Social and political scientists brought their analytical focus towards the political systems in which courts function. They explored how judiciaries fulfil their distinct institutional roles in relation to other branches of government (Hamlin, Reference Hamlin2014; Ellermann, Reference Ellermann2013; Bonjour, Reference Bonjour2016; Opeskin, Reference Opeskin2012) and documented that the courts can enable both expansive and repressive dynamics when it comes to controlling migration (Alagna, Reference Alagna2022; Anderson, Reference Anderson2010).

This article seeks to contribute to this literature, both theoretically and empirically, with a focus on immigration appeal decisions and administrative justice in Canada’s Quebec province. The majority of existing research on justice and migrants’ rights has primarily concentrated on the work of higher courts and did not examine administrative tribunals specifically (for exceptions see Johannesson, Reference Johannesson2018; Hamlin, Reference Hamlin2014; Thomas, Reference Thomas2011). This is of significance as administrative tribunals revisit a substantial number of immigration decisions, surpassing the caseload handled by higher courts.

Administrative tribunal judges are often characterised as members of a hidden judiciary that are placed within the executive branch (Guthrie et al., Reference Guthrie, Rachlinski and Wistrich2009; Schreckhise et al., Reference Schreckhise, Chand and Lovrich2018). Their primary role is reviewing bureaucratic decisions. Operating within administrative tribunals with quasi-judicial responsibilities, administrative judges carry out adjudication similar to court judges. However, they typically serve as employees of their respective tribunals, leading to a combination of their roles as judges and bureaucrats (Lens, Reference Lens2012). In their capacity as judges, they conduct hearings, assess evidence, interpret applicable laws and deliver legal rulings (Portillo, Reference Portillo2017; Tomkinson, Reference Tomkinson2018). As bureaucrats, they execute public policies and function within a hierarchical institutional framework (Thomas, Reference Thomas2011). Their role, therefore, is simultaneously legal and policy-oriented (Thomas and Tomlinson, Reference Thomas and Tomlinson2017). Within the immigration sector, where opportunities for challenging bureaucratic decisions are limited and administrative discretion holds significant influence over individual cases, these judges have the potential to fulfil a crucial role in examining and scrutinising the actions of the immigration bureaucracy. Doing so, they may contribute to the expansion of migrants’ rights, one file at the time.

In this article, we explore this possibility through a focus on immigration appeals and administrative justice in Canada’s Quebec province. Our analysis is based on an original database of all immigration appeals finalised by the Administrative Tribunal of Quebec since its establishment in 1998 until 2020 (N = 893). This independent public agency is a generalist administrative tribunal of last instance, unique in Canada. Regarding immigration policy, it hears appeals of the decisions taken by the Quebec Immigration Department on negative determinations of permanent residency acquisition and family reunification. A positive decision on an appeal can provide significant public benefits to immigrants and their families such as right to admission, to work, to health care, to education, and eventually to obtain permanent residency and citizenship.

By closely examining the outcomes and the grounds of immigration appeal decisions through a longitudinal approach, we look at how administrative tribunal judges in Quebec decide immigration appeals, and what factors they consider in their reasoning and explanations. In line with recent work casting doubt on the potential of courts as a venue for the expansion of immigrants’ rights, the analysis of immigration appeal decisions shows that the contribution of Quebec tribunal judges to promoting migrants’ rights is limited. Even though the legislation gives them the power to decide both questions of law and fact, we find that tribunal judges uphold the bureaucratic decision in the vast majority of cases (N=840, 94 percent of decisions) noting the inability of migrants to meet the annual income requirements (N=584, 69.2 percent of decisions). We conclude that administrative justice is not a venue through which migrants’ rights are expanded in Quebec.

The article proceeds as follows: the next section explains our theoretical approach. Afterwards, we describe the policy context and our methodology. The results, discussion and conclusion follow.

2 Administrative justice and tribunal judges

Administrative justice as a concept and an analytical tool gained importance during the last decades for examining administrative processes and decisions, especially within the Commonwealth. Administrative justice is currently a recognised field of study and refers to the processes governments use to make determinations about individual rights and entitlements, and the mechanisms in place to challenge these decisions (Hertogh et al., Reference Hertogh and Hertogh2022).

This definition brings together three scholarly conceptions regarding administrative justice: external, internal and integrated (Adler, Reference Adler2012). The external perspective focuses on the role of courts and judicial review in providing accountability mechanisms (Ford, Reference Ford, Flood and Sossin2018) ‘as the principal means of articulating general standards of legality that apply across the disparate range of individual administrative processes’ (Thomas, Reference Thomas2011). The internal perspective sees judicial review as exceptional, given the superior courts only review a small percentage of administrative decisions. In this approach, external perspective is insufficient in providing an effective check on routine administrative processes or enhancing bureaucratic decisions (Adler, Reference Adler2010). Hence, this perspective focuses on the large number of first instance decisions and aims to improve internal decision-making and accountability mechanisms in place through recruitment, training and performance management for government departments (Adler, Reference Adler2012; Cowan et al., Reference Cowan2017). Finally, the integrated approach attempts to combine these two perspectives and proposes that many actors and institutions can play a positive role in enhancing administrative justice. It insists that administrative justice is pursued in diverse contexts, such as frontline assessments (Cowan et al., Reference Cowan2017), complaint handling by Ombudsman (Buck et al., Reference Buck, Kirkham and Thompson2007), administrative review and quasi-judicial decision making processes within administrative courts and tribunals (Lens, Reference Lens2012; Tomkinson, Reference Tomkinson2018; Tomkinson, Reference Tomkinson2020). Given the diversity of these settings, researchers and practitioners tend to refer to a system, landscape, framework, or terrain of administrative justice (Sossin, Reference Sossin2017; Doyle and O’Brien, Reference Doyle and O’Brien2020; Abraham, Reference Abraham2012; Thomas, Reference Thomas2011; Tomkinson, Reference Tomkinson2023).

It is possible to observe two broad perspectives specifically on administrative tribunals and their contribution to administrative justice and public policy (Thomas, Reference Thomas2011; Thomas and Tomlinson, Reference Thomas and Tomlinson2017). Some consider tribunals as mechanisms for adjudication that are primarily focused on resolving disputes that operate independently from the wider policy process (Sossin, Reference Sossin2017; MacDonald, Reference Macdonald1993; Guthrie et al., Reference Guthrie, Rachlinski and Wistrich2009; Chand and Schreckhise, Reference De and Schreckhise2020). According to this perspective, administrative tribunals provide individuals dissatisfied with bureaucratic decisions the chance to seek remedies from an impartial and quasi-judicial adjudicative body. As such, tribunals’ role is confined to adjudication and does not encompass policy functions (Ellis, Reference Ellis2013).

Contrary to this legal perspective, others argue that administrative tribunals should be regarded as incorporating adjudicative elements within a framework for implementing public policy (Tomkinson, Reference Tomkinson2023; Thomas, Reference Thomas2011; Thomas and Tomlinson, Reference Thomas and Tomlinson2017). While they must maintain institutional separation and independence from the bureaucracy, they are integral to the overall process of policy implementation (Noreau et al., Reference Noreau2014; Houle and Sossin, Reference Houle and Sossin2006). Through their role in adjudicating disputes between individuals and bureaucracy, tribunals enable affected individuals to get their grievances heard and to actively participate in the policy implementation process. Hence, they are responsible for public policy through ‘the legal work of the administrative state’ (Merriman, Reference Merriman2021, p. 214). Relatedly, research on decision-making practices of administrative tribunal judges in the United States and Canada looks at how judges treat applicants’ justice claims and whether they align themselves with the service they are scrutinising (Lens, Reference Lens2012; Portillo, Reference Portillo2017; Tomkinson, Reference Tomkinson2018).

In this article, combining the integrated and the policy approach, we conceptualise tribunal judges as policy actors who can potentially advance administrative justice through interpretation and implementation of immigration rules. As they decide on appeals, tribunal judges take part in the policy process, produce not only individual judgments but also meanings and clarifications regarding administrative and legal concepts related to immigration. The next section explains the functioning of the administrative tribunal that is the object of this analysis.

3 Administrative Tribunal of Quebec and adjudication of immigration appeals

The Administrative Tribunal of Quebec (Tribunal administratif du Québec, from now on TAQ) is a unique justice organisation in Canada. It is a provincial, generalist, last instance administrative tribunal, similar to The Administrative Appeals Tribunal in Australia (Ellis, Reference Ellis2013). Created in 1998, with The Act Respecting Administrative Justice, SQ 1996, c 54, the TAQ hears appeals of decisions by Quebec ministries, public agencies and municipalities. While most tribunals in Canada act within specific policy areas, the creation of a generalist tribunal like TAQ was based on the main objective of offering Quebec residents a single-window, independent and impartial tribunal, so that they could have the decisions that affect their rights reviewed and their disputes resolved (TAQ, 2005).

While Canadian administrative tribunals are public agencies that act at arm’s-length and report to the parliament through specific government departments, TAQ is designed to be independent and separate from any public body. When the TAQ was created, the mandate of tribunal judges was limited to five-year terms and they could be re-appointed by Cabinet decision, similar to other administrative tribunal members in Quebec and Canada. Due to the sustained litigation efforts of the Bar of Montreal,Footnote 1 the Government of Quebec adopted amendments to the relevant law in 2005. Since then, the tenure and judicial office protections offered to the TAQ judges are similar to regular court judges: they can hold office during good behaviour, and ‘specific provisions acknowledge their independence and impartiality’ (de Kovachich, Reference De Kovachich, Molinari and Farrow2013).

For Quebec legal scholars and practitioners, the unique character of the TAQ can be explained through the distinctive character of administrative law in Quebec (Houle, Reference Houle2009; Noreau et al., Reference Noreau2014). In the province, the state came to be seen as the promoter of interests of a small and unique francophone minority in North America (Lemieux, Reference Lemieux, Taggart and Huscroft2006) and the trustee of collective interests in Quebec. Reflective of this, the TAQ was established through a concerted process with the province’s legal profession. Through working groups, legal scholars contributed to establish safeguards in order to prevent and remedy arbitrary conduct by public officials, and promoted the idea of a generalist tribunal, which resulted in the creation of the TAQ (Houle, Reference Houle2009).

Currently, the TAQ has 121 tribunal judges who have practiced as ‘lawyer, notary, physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, accredited appraiser, urban planner, engineer or agronomy engineer’. It has five different sections: social affairs, mental health, immovable property, territory, environment and economic affairs. The Social Affairs Section, with its fifty-three full-time and nine part-time tribunal judges,Footnote 2 hears more than 80 percent of the appeals TAQ receives in matters such as compensation, pension schemes, social assistance or income support, health and social services, education, road safety and immigration.

Immigration appeals that the Social Affairs Section hears are adversarial; the parties are the appellant and the Quebec Immigration Department (Ministry of Immigration, Francisation and Integration, hereafter, MIFI). While in some TAQ sections, appeals are decided by a panel of three judges, in immigration cases only one tribunal judge presides over and finalises the appeal. Through a quasi-judicial hearing, tribunal judges hear and examine evidence from both parties and hear other witnesses. According to Article 15 of The Act respecting administrative justice, when the TAQ hears a case, the judge ‘has the power to decide any question of law or fact necessary for the exercise of its jurisdiction’. The same Article specifies that in the case of an administrative appeal, the TAQ may confirm, modify or reverse the first instance decisions, and if necessary, it may render the decision that, in its opinion, should have been made initially. Therefore, TAQ judges’ decision-making powers and discretion are integrated within the administrative justice legislation and was also confirmed by the Quebec Court of Appeal and the Superior Court judgments.Footnote 3

According to previous research, tribunal judges who enjoy important procedural protections, like administrative law judges (ALJ) at the U.S. Social Security Administration – such as security of tenure and immunity from performance management – tend to align less with the policy preferences of their tribunal and elected officials compared to their counterparts, such as immigration judges who lack these protections (Chand and Schreckhise, Reference De and Schreckhise2020). Yet, Thomas (Reference Thomas2011) reminds us that consistency of decisions is an important value for judges who examine asylum appeals in the UK. As we explained above TAQ judges enjoy important procedural protections. Before we examine the impact of the unusual statutory protections offered to the TAQ judges on immigration appeal decisions, in the next section, we will explain the broad contours of Quebec’s immigration policy.

4 Quebec immigration rules and procedures

Since 1991, Quebec has had distinctive power in immigration policy within Canada’s federal system. As part of the Canada-Québec Accord Relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens (Québec, 2000), the province ‘has sole responsibility for the selection of immigrants destined to that province and Canada has sole responsibility for the admission of immigrants to that province’ (Québec, 2000). Article 12c of the legislation clarifies that ‘Canada shall not admit any immigrant into Québec who does not meet Québec’s selection criteria’ (Québec, 2000). In this context, admissibility refers to an assessment about criminality, security and health requirements (e.g. no criminal record or absence of a reportable disease). The MIFI selects permanent residents through either a scoring system or an assessment of whether candidates meet established program requirements. For example, to select economic migrants, the MIFI rates individual files on issues such as knowledge of the French language, education and employment sectors. For other program streams such as family reunification, selection will also include decisions about whether candidates respect financial thresholds and the family member they propose to sponsor fits the definition of family unit. Public servants make these decisions based on the documents submitted by applicants and their representatives.

In practice, individuals who want to immigrate to Quebec must first apply to the provincial government rather than the government of Canada. The MIFI assesses these applicants and decide whether to deliver a Quebec selection certificate (certificat de sélection du Québec, from now on CSQ). Afterwards, approved applicants can ask for permanent residency from the government of Canada which assesses whether candidates meet the admissibility thresholds established in the federal Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (S.C. 2001, c. 27) and the associated regulations. Issuance of CSQ applies to the permanent resident visa category.

For family reunification programs, citizens and permanent residents of Canada can sponsor close family members for permanent immigration (Gaucher, Reference Gaucher2018). In this context, close family members include partners (spouses, common law partner, etc.), dependent children, parents and grandparents, brothers and sisters who are under 18-years-old, single and orphaned as well as adopted children. Individuals who want to sponsor close family members for immigration must first apply to the federal government to confirm the admissibility of their case. Once this step is completed, applicants must submit an undertaking application to the Quebec government that will proceed to the selection step. For cases that are approved by the province, applicants must then ask for permanent residence for the sponsored individual from the federal government. Because of the norms set out in the 1991 immigration agreement, the federal government does not process applications that have not been accepted by the Quebec government (Bélanger and Candiz, Reference Bélanger and Candiz2019).

In Quebec, sponsors are responsible for demonstrating that their relationship to their relatives is genuine and fits the criteria established by the sponsorship program (Québec, 2020). As part of the program, sponsors commit to support their dependent financially for a pre-defined period. Should sponsored individuals use Quebec social assistance or other specific health or housing programs during that period, the sponsor will have to reimburse the government for these costs (Québec, 2020). Individuals sponsoring spouses and children over sixteen years old are responsible for a three-year period whereas those sponsoring younger children, parents and grandparents enter into a ten-year financial commitment (Québec, 2020). Therefore, in their application, future sponsors must demonstrate that they meet program requirements by proving that they are capable of financially supporting the family member they want to sponsor. The province sets out basic annual income threshold for sponsorship, which is contingent on a minimum family income cut-off, based on the number of family members. As an example, a single individual needs a basic gross income of $24,602 and a family of five must have a basic gross income of $52,482 (Québec, 2023). In addition to this, the government of Quebec requires proof of additional income based on the number and characteristic of sponsored persons, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Additional income required for sponsorship in Quebec, 2021

Source: (Québec, 2023).

As explained on the Quebec government website, the income requirements for sponsors are in effect from January 1 to December 31 and are adjusted each January 1. The amounts shown in this table for 2021 are no longer available online.

5 Data collection and analysis

In this article, we analyse immigration appeal outcomes and on what basis immigration these decisions are made in Quebec. Our analysis is based all immigration appeals finalised by the TAQ since its establishment in 1998 until 2020. To our knowledge, this is the first study that adopts a longitudinal approach to examine immigration appeals and administrative justice.

All decisions of the TAQ are available to the public in text-searchable format through the Société québécoise d’information juridique (SOQUIJ) legal decision repository. SOQUIJ is a specialised arms-length organisation mandated by the Quebec legislature. It is under the oversight of The Department of Justice to collect, collate and make searchable all tribunal and courts decisions in Quebec and in Canada. SOQUIJ also publishes French-language digests and analyses for legal professionals. As a state-mandated organisation, the SOQUIJ has an obligation to ensure that its legal decision repository contains all decisions issued in Canada and in Quebec.

Using this depository, we first conducted keyword searches to identify targeted decisions by the TAQ. In order to be exhaustive, we searched with all successive names of the Quebec Immigration Department since 1998.Footnote 7 Each decision was downloaded from the SOQUIJ website for the constitution of our database.

Following this procedure, we constructed a database that includes 893 decisions taken between 1998 and 2020 based on two kinds of appeals:Footnote 8 cancelation of applications for permanent residency or CSQ provision, and rejection or cancellation of a family sponsorship application.Footnote 9 Since our focus was on immigration appeals, we did not include appeal decisions on disputes of immigration consultants.

The third author coded all decisions using a validated procedure.Footnote 10 The coding first concentrated on the production of data about the case (date, neutral reference of decision, file number), the name and the gender of the judge, the availability of legal representation, the gender of the appellant, the reason for the appeal and the outcome of decision rendered by the judge (negative, positive or absence of decision). The focus on decision outcomes was complemented with a second round of reading, coding and analysis that revealed the reasons tribunal judges offered for their decisions.

Finally, we conducted a qualitative content analysis of positive decisions to examine whether and to what extent tribunal judges can advance administrative justice regarding migrants’ rights. Our analysis was theory-based and was guided by our research question (Mayring, Reference Mayring2019) as it focused on examining under what conditions tribunal judges render positive decisions that expand migrants’ rights.

6 Findings

In what follows, we first document that tribunal judges in Quebec reject most of the immigration appeals they hear. Afterwards, through a careful look at the justifications of negative decisions, we show that TAQ judges mostly confirm bureaucratic decisions and note the inability of appellants to meet the annual income requirement. Finally, a deep dive into positive decisions illustrates that while TAQ judges consider the personal circumstances of the appellants when there is delay by allowing the filing of the appeal, they rarely reverse the decision in favour of the appellants.

6.1 Immigration appeal outcomes: confirming bureaucratic decisions

A central first order finding comes out of descriptive statistics about TAQ decisions: tribunal judges reject most appeals, as shown in Table 2. In more than 94 percent of appeals tribunal judges upheld the bureaucratic decision (n = 840). In less than 5 percent of the cases, they agreed with the appellant (n = 43) and they did not render a decision for around 1 percent of appeals (n=10).Footnote 11

Table 2. Breakdown of appeal outcomes

Our database allows us to examine the influence of the judge’s and the appellant’s gender and the impact of counsel. However, these variables did not yield statistically significant results.

Men and women appellants submit comparable number of appeal requests to the TAQ (49 percent men, 46 percent women, 5 percent undisclosed). Each gender has their appeal rejected at an equivalent rate. Forty-six administrative judges issued decisions between 1998 and 2020, with one judge being especially active (Chahé-Philippe Arslanian, with 51 percent of all the decisions during the examination period) and nine other judges adjudicating 28 percent of the appeals. Regarding the gender of judges, no clear pattern of decision is discernable across TAQ judges; they issue positive and negative decisions at a comparable rate with no statistically significant differences. Legal counsels represent 14 percent of the appellants to the TAQ and the presence of counsel does not improve the appellants’ chances of getting a positive result.

While documenting that tribunal judges in Quebec reject most immigration appeals is an important finding, it does not explain on what basis TAQ judges arrive at negative outcomes. This demonstrates the need to go beyond the appeal outcomes and to consider the rationales tribunal judges put forward in their decisions. Focusing on grounds for appeal decisions, in the next section, we investigate how TAQ judges reach at negative decisions. All citations of legislation and appeal decisions are translated from French to English.

6.2 Grounds for negative appeal decisions: adherence to immigration rules

Examining judges’ reasoning is an important aspect of the scholarship that investigates the factors that influence judicial decision-making (Sisk et al., Reference Sisk, Heise and Morriss1998; Friedman, Reference Friedman2005). This reasoning can be inferred from the grounds of decisions, meaning where judges offer a written analysis of the case and explain how they arrived at the conclusion. Our analysis on the grounds for negative appeal decisions follows this logic and documents that TAQ judges adhere to immigration policy and regulations, especially to the ones related to income and program requirements.

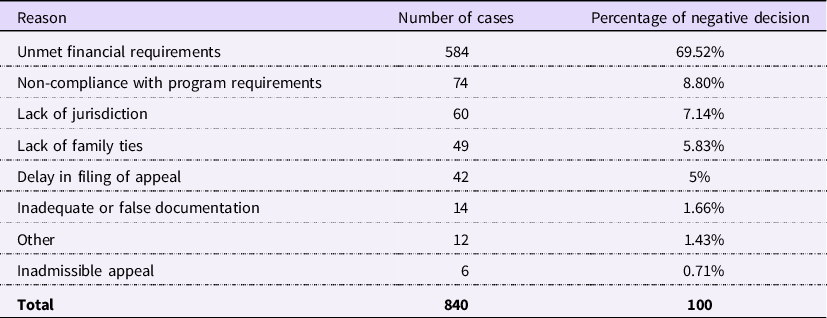

Table 3, below, illustrates the different categories of reasons TAQ judges offer for rejecting the appellants’ requests. While the reasons are diverse, almost 70 percent of appellants receive negative decisions because they have not fulfilled the financial requirements (N=584 decisions), including relying on government income support or not meeting the financial thresholds for sponsorship.

Table 3. Grounds for rejected appeals, 1998–2020

The prevalence of refusals based on income requirement is an indication that TAQ judges do not reinterpret immigration programs’ financial rules and make exceptions for some appellants. These negative decisions are typically brief, spanning about two-three pages, with the tribunal judge clarifying the need to assess the validity of the government’s decision and emphasising the appellant’s failure to meet the financial criteria, as exemplified by the following decision excerpt:

[4] The Tribunal must determine whether the respondent’s decision is well founded in fact and in law…

[5] The Tribunal, after considering all the documentary evidence on file, concludes that the decision of the respondent should be confirmed.

[6] The applicant had to show that their income, for the twelve months preceding the respondent’s decision, was at least $65,488.

[7] The documentary evidence shows that the Applicant’s income is far below the minimum amount required (2014 QCTAQ 11440).

In their justifications, tribunal judges also refer to the need to respect the legislation as well as the bureaucratic decision, even when they recognise that the separation of a family because of financial considerations can be challenging:

[17] It is clear that the situation is difficult for the applicant and her family. However, the Tribunal cannot grant this application, as the legislation does not provide any discretion to overturn the decision in dispute on humanitarian grounds (SAS-M-084020-0305).

Almost 9 percent or seventy-four of the negative decisions are based on judges confirming that the appellants do not comply with the requirements of the program to which they applied. Regarding family sponsorship cases, which involve financial considerations, this often encompasses factors such as outstanding child support, unpaid taxes, reimbursement for government assistance, or unfulfilled obligations from previous sponsorship cases. In such instances, judges commonly reaffirm the program’s regulations and note the applicants’ non-compliance. In some cases, they follow policy guidelines even when they are not required to do so. Acting this way, they reproduce and justify the bureaucratic decision (Lens, Reference Lens2012; Miaz and Achermann, Reference Miaz and Acherman2021). In case 2013 QCTAQ 01935, the appellant challenges a rejection of undertaking application for sponsoring her daughter. She explains that she has another child who is a fifteen-year-old that lives with her ex-husband. She refuses to pay child support since her ex-husband had not paid it either from 2001 to 2009 when her child lived with her. Accordingly, she argues that she meets the income threshold to sponsor another child. The presiding judge disagrees with this explanation and explains that a fifteen-year-old child is a dependent that the appellant should take care of financially. Furthermore, the judge quotes the legal representative of the Department of Immigration who refers to immigration guidelines:

[35] The Respondent also refers to the Immigration Procedures Manual in Chapter 3 that sets out the conditions for accepting an undertaking.

[36] Article 4.2.1 reminds that, in addition to herself, the guarantor’s family unit includes her dependent children, even if they do not live with her or if they live abroad.

[36] In addition, section 4.4.2 specifies that the applicant’s assets must be divided according to the expected date of undertaking, which in this case is three years.

[36] While this manual does not bind the Tribunal, it offers the advantage of similar treatment for all, which is desirable. (our emphasis)

The TAQ judge’s reasoning in this appeal illustrates the importance of consistency in tribunal decision-making for this particular judge but also her adherence to immigration rules. On its website, the MIFI describes the scope and the purpose of the Guide des procédures d’immigration (Immigration Procedures Manual, 2021)Footnote 12 as a ‘reference tool on immigration procedures’ developed by the Department. The Manual ‘describes the procedures for each temporary and permanent immigration program and is an interpretative source for departmental staff in making decisions on applications submitted to the Minister’. This particular case is an example of how the tribunal judge tries to ensure consistency as an important policy and administrative justice value (Thomas, Reference Thomas2011).

The lack of jurisdiction constitutes the third most common reason judges offer to reject the appeal in over 7 percent of negative decisions. In these cases, the applicants appealed because the MIFI did not issue their permanent residency or selection certificate. In these decisions, the TAQ judges explain the applicable law as the following: ‘In this case, the decision of the Ministry center on the rejection of the selection certificate. Only the cancellation of the certificate can be challenged before the Tribunal’ (our emphasis, in 2018 QCTAQ 06259). The Quebec Superior Court handles applications for judicial review of rejection decisions.

Almost 6 percent of negative decisions are based on the findings related to the family unit. In these cases, TAQ judges confirm the government decision that does not recognise family ties or relations as valid. Justifications for such rejections include potential sponsors not meeting the definition of family ties or the needs threshold as stipulated in the program, such children being too old to be considered as dependents as well as divorces or adoptions that are not recognised by Quebec or Canadian law.

Forty-two decisions, or 5 percent of the negative outcomes, centre on delay regarding statutory time limits. The Article 106 of The Act respecting administrative justice, SQ 1996, c 54 allows appeals within sixty days after the decision is rendered. Article 106 stipulates that:

The Tribunal may relieve a party from failure to act within the time prescribed by law if the party establishes that he was unable, for serious and valid reasons, to act sooner and if the Tribunal considers that no other party suffers serious harm therefrom. (our emphasis)

Relatedly, appeals submitted after statutory time limits are not automatically rejected. TAQ judges first hold preliminary hearings where the appellants need to explain why they were late to initiate the appeal of the contested decision. In these cases, the government representative underlines the delay and highlights the inadmissibility of the appeal. In their explanations, TAQ judges indicate that they must decide whether they dispose discretionary power to relieve the appellant of their failure to submit their application on time (2019 QCTAQ 07227). They do not consider applicants’ justifications for late appeals as reasonable when the latter simply explain that they were not aware of a time limit within which they could contest the initial decision (2014 QCTAQ 06402). As we will explain below, in eighteen cases judges found the appellants’ explanations regarding delay in filing the appeal valid and allowed them to go forward.

Finally, in less than 4 percent of the negative appeals, judges confirm the decision made by bureaucrats regarding improper, false or inadequate documentation and incomplete file (N=14). Additionally, they approve the decision based on changed circumstances concerning the applicant or the initial decision, rendering the appeal irrelevant. (N=12). Finally, in six cases the judges conclude that the appeal request was inadmissible when the applicants simply presented their disagreement with the bureaucratic decision without offering any further arguments.

6.3 Grounds for positive decisions: limited role of tribunal judges in promoting administrative justice

This section presents the grounds for positive immigration appeal decisions, both for authorisations to file an appeal despite the delay and overturned bureaucratic decisions. First, examining reasons where TAQ judges allowed late applicants to file an appeal, we document that TAQ judges authorise appeals when the applicants exceed statutory time limits because of situations that are beyond their control. Afterwards, our analysis of the reversed decisions shows that similar to confirmed ones where the tribunal judges sided with the MIFI, the main issue was income requirements. The most significant findings are the following. First, TAQ judges rarely take decisions in favour of migrants (N=25, less than 3 percent of all decisions). Second, we observe that during the initial years of the TAQ, tribunal judges had a more generous interpretation of income regulations. After 2003, we note a stricter adherence to immigration rules.

As explained above, we initially identified forty-three positive decisions. Following our content analysis, we found that these decisions fall into two categories, either authorisations to make an appeal despite the delay or the overturned decisions in favour of the appellants. Table 4 (below) illustrates this distinction. In eighteen cases, representing 2 percent of all appeal decisions, tribunal judges gave the green light to immigrants who wanted to appeal the negative bureaucratic decision.

Table 4. Breakdown of positive decisions

A close look at these decisions reveals that TAQ judges have some room for manoeuvre in their determinations when they consider delays. Examining whether the appellants provided justifications for exceeding the time limit established with legislation, TAQ judges consider the personal circumstances of immigrants. For example, they grant permission to appeal when immigrants attempted to contest the negative decision at the wrong instance, such as sending their appeal to the Department of Immigration instead of the tribunal (2014 QCTAQ 1145). They pay close attention to the appellants’ level of education (2014 QCTAQ 09990), their ability to understand and communicate in French or English (2011 QCTAQ 07240), their desire to seek legal representation (2010 QCTAQ 04971) and life circumstances, such as the sickness or death of a family member (2011 QCTAQ 10161 and SAS-M-40154-9904).

Alongside these determinations on personal circumstances, TAQ judges also clarify the meaning of the sixty-day limit for initiating an appeal in several decisions.Footnote 13 They conclude that the counting should start from the day the appellant received the decision and not from the day the decision was made or sent out. It is important to indicate that while the TAQ judges deemed these eighteen appeals admissible, and these cases went to a full hearing, none of them resulted in a positive decision.

When we turn our attention to accepted appeals, we observe that TAQ judges overturn the initial decision in favour of immigrants in twenty-five cases, which represent 2.8 percent of all appeal decisions. As Table 5, below, indicates, tribunal judges’ reasons principally centre on income requirements and less frequently on compliance with programs, documentation and family ties. In what follows, we examine these reasons in more detail.

Table 5. Justification for accepted appeals, 1998-2020

Tribunal judges’ reasoning in positive appeals regarding income requirements show that they do not take the factual determinations of immigration bureaucrats at face value, they conduct their own calculations to assess whether the immigrants who want to sponsor a family member have the required revenue. What is more, TAQ judges took most of these positive decisions (fourteen of twenty decisions) during the first few years of the tribunal between 1998 and 2003.Footnote 14 This finding might be considered as consistent with the TAQ’s mandate to interpret and clarify law, which is likely to be more ambiguous when the laws are new. TAQ judges might be intervening less later on because the MIFI public servants have learned how to uniformly apply fact to law, per the tribunal’s guidance. During this period, through reconsiderations of the first-instance assessments about official documents, such as federal and provincial revenue agencies, bank statements and the appellants’ testimonies judges correct bureaucratic mistakes, indicating that a positive decision should have been taken at the first instance. While they specify that the role of the TAQ is to examine whether the bureaucratic decision was well founded in fact and in law, in these early tribunal decisions, administrative judges demonstrate a more generous interpretation of law that favours migrants. They do so by basing revenue requirements on the household income rather than the individual, considering recurrent income support benefits as revenue and not imposing the sponsorship income threshold if the family members are financially self-sufficient. Further, as they correct errors in revenue calculations, they praise the efforts of immigrants who work long hours. In what follows, we examine these justifications closely.

In three different appeal decisions that they made between 2001 and 2003, tribunal judges explain that the responsible immigration official failed to consider the entire income of the household, such as retirement savings, real estate and pay increases as they recalculate the household income (SAS-M-078248-0209; SAS-M-069222-0108; SAS-M-060614-0007). After giving detailed information on the respective jobs of the spouses, their hourly salary, recent raises, the net worth of their house, employer contribution to retirement savings, the TAQ judge explains in his decision dated 6 April 2001:

[19] From all the evidence, it is very clear that the applicant and her husband informed the public servant of an upcoming change in their income.

[20] The couple’s current income is approximately $70,000. In fact, the applicant’s income, considering both jobs, is around $8,800, the income from the husband’s job is $60,109, the various interests on the amounts of $7,445 and $3,821, as mentioned on the evaluation form, amount to $530; the interests on the amount of $3,000 held in retirement savings and the income on the locked-in capital of $25,000 amount to $1,316; which brings the couple’s total annual income to $70,755 (SAS-M-060614-0007).

Similarly, in a decision dated 9 May 2000, the TAQ judge overturned a negative bureaucratic determination that indicated that the applicant did not have the required income to sponsor his parents and brother (SAS-M-040107-9812). The tribunal judge explains that the public servant who assessed the financial capacity of the applicant to sponsor his family members concluded that not only the applicant’s income was insufficient between 1997 and 1999 but also that he did not recognise that the applicant had any earnings. According to the applicant’s testimony, since 1994, he works as a machine operator in a company and every year he is laid off systemically for varying periods during fall and winter months when the company has fewer contracts. During that time, he collects unemployment benefits but also remains on his employer’s recall list in case work is available. He adds that since May 1997, he has also been working as a delivery person in a painting company as a self-employed worker. Below, the presiding judge explains that normally income derived from financial assistance programs is not a part of revenue calculations. However, ‘the recurring and systematic character’ of this assistance, as well as the permanent and stable character of the employment allows the applicant to meet the financial requirements:

[15] As argued by the counsel for the respondent, in case law, unemployment benefits do not amount to income within the meaning of section 45 “since it does not constitute income that is likely to be available to the guarantor for the duration of the undertaking.” The Tribunal fully agrees with this proposition, but considers that a distinction should be made where, as here; there is a clear recurrence of this type of income over a number of years, due to the layoffs themselves being recurrent and systematic, with a recall list of employees.

[16] The Tribunal is therefore of the view that, in this particular case, there is reason to consider the recurrent and systematic nature of the layoffs and recalls of the applicant by the employer over a number of years. The employment is nonetheless of a permanent and stable nature, so that the unemployment benefits received by the applicant can be taken into account in assessing the applicant’s financial capacity to carry out the sponsorship (emphasis in original).

TAQ judges clearly indicate in their decisions that income requirements aim to ensure that sponsors can support their family members without resort to government assistance. However, this does not mean that they cannot make exceptions. In an appeal dated 7 August 2001, the tribunal judge observes that the applicant, who is a single mother, does not meet the financial requirements to sponsor her parents. She came to Canada as a pregnant, single woman in 1994. Her parents have lived with her on a tourist visa since the birth of her child. They leave Quebec every six months to renew their visa and come back within two weeks. They do not have any health problems. They provide their daughter financial and moral support as the child’s father threatens their daughter with child abduction. They own property in Morocco, which they are ready to sell and settle in Quebec permanently. Taking into account these factors, the judge allowed the appeal (SAS-M-062540-0011).

A final type of positive decision regarding income requirements that is worth examining illustrates the very long work hours some migrants need to undertake to support themselves and their family members. In an appeal decision dated 13 August 2003, the tribunal judge observes that according to the first-instance decision the applicant does not meet the required income range to sponsor his parents and sister. In his summary of the facts of the case, the TAQ judge writes that according to the testimony of the applicant he has been working for almost ninety hours per week for the last few years:

[4] He works 14 hours in a restaurant as a kitchen assistant, 40 hours in another as a cook and 35 hours in a factory as a machine operator …

[6] He has been working as an operator since January 1999, as a kitchen assistant since June 2000 and as a cook since April 2002.

[7] Prior to working as a cook, he worked a minimum of 40 hours at a convenience store.

[8] On the 2002 Revenue Canada Notice of Assessment, his total income is shown as $39,738.

[9] It is very clear from the evidence that the Applicant maintains a very heavy workload; however, he has persevered to the present day and there is no reason for the Tribunal to doubt that the Applicant will not continue to work three jobs…

[11] The consistency, regularity, and duration of the employment pattern was demonstrated by the applicant (our emphasis, SAS-M-079942-0211).

In this appeal, the TAQ judge explicitly recognises the weight and the stability of the workload assumed by this migrant who wants to bring his family to Quebec. He can meet income eligibility requirements because of his excessive working hours. Commanding on the ‘consistency, regularity and duration’ of the applicant’s employment pattern, the TAQ judge notes his belief that the applicant will maintain his three jobs in the future to sustain his family.

The positive decision on program requirements dated 14 February 2003, concerns the undertaking application of a woman who wants to sponsor her new husband (SAS-M-061364-0008). Initially, her application was rejected since she did not pay child support to her ex-husband. In his reversal decision, the TAQ judge considers the applicant’s oral testimony and documentary evidence where she explains that when her husband took custody of their daughter in June 1999, she paid child support during summer 1999. She married her current husband in May 1999, made a sponsorship application right away and they left for Portugal at the end of June 1999 to wait for the finalisation of his permanent residency application. Even though she had informed the government of Quebec and Canada that she was taking unpaid leave from work, consequently she would not be able to pay child support, this information was not taken into account. Considering the applicant’s explanations during the hearing as well as her bank information, the TAQ judge reverses the decision.

In the positive decision regarding family ties, the presiding judge notes that the MIFI rejected the applicant’s request to sponsor a family member with her partner since her situation did not respect the second paragraph of Article 66 of immigration regulations, which specify that the applicant ‘must be a Quebec resident and ordinarily reside in Quebec’.Footnote 15 After offering the following explanation, the TAQ judge specifies that the analysis of relevant concepts such as cohabitation, living together or marital life is exercised within a factual framework; hence, the judge must determine whether there is de facto absence of cohabitation:

[9] According to the financial assessment supporting the respondent’s decision, the respondent bases the refusal of the undertaking on the fact that the appellant does not reside in Quebec, and that she and the co-sponsor are not a “couple” and therefore cannot be common-law partners, since they live at different addresses.

[10] The concept of marital life has been extensively defined in the Tribunal’s case law. It refers to three criteria: cohabitation, mutual aid and, to a lesser extent, common report.Footnote 16

[11] In the present case, it is recognized that the wife must stay in another residence for her work at an American university (2020 QCTAQ 05160).

Citing the Supreme Court judgment Hodge v. Canada,Footnote 17 which treated the meaning of legal relationship between spouses in terms of cohabitation, the TAQ judge explains cohabitation in this case should not be examined through the lens of co-residence (Hodge v. Canada). Two people can cohabit even if they do not live together. He maintains that the only reason the couple does not live together is the applicant’s job. The couple also demonstrated their family ties by getting married in July 2018. Also citing Quebec Civil Code, he indicates that, the applicant demonstrated that her main place of residence is in Quebec and not in the United States. However, for sponsoring a family member, according to the Article 76 of immigration regulations, only income earned, or property held in Canada can count as income. In that sense, while the applicant alone does not meet revenue requirements, her spouse acts as co-sponsor and he meets the income threshold for family reunification.

According to Article 3.2.2. of Quebec Immigration Law, MIFI can cancel a selection or undertaking certificate if the application contains false or misleading information or document. This means that there is some room for interpretation. Three positive decisions regarding documentation centre on two arguments, obligation to justify that information is false or misleading and due diligence and the credibility of the applicant. One case is based on the cancelation of an applicant’s permanent residency where her ex-husband informed the MIFI that the applicant had submitted bogus documents and misleading information regarding her employment status (2018 QCTAQ 03333). The other concerns a negative family reunification decision where the applicant wants to sponsor his two minor, orphaned nieces and the MIFI does not consider the official documents as authentic (SAS-M-061066-0008). In both cases, TAQ judges conclude that public servants cannot simply say that a document is a forged and make a negative decision, they have to ensure that the document is not genuine or that the communicated information is misleading. Therefore, the burden of proof lies with the MIFI and not with the applicants. The final case contains both a negative and a positive determination. It concerns the cancellation of CSQ for permanent residency for six couples who failed to declare that they have retained the paid services of an immigration consultant who was no longer a member of the Québec directory of immigration consultants recognised by the MIFI (2020 QCTAQ 01837). In his reasons, the TAQ judge explains that the appellants cannot be blamed for not knowing whether the consultant was authorised to practice or not, but they are responsible for not having declared the true nature of the contractual relationship and ultimately for making a false declaration. After quoting the following excerpt from the appellants’ declaration regarding the role of the immigration consultancy firm the TAQ judge explains that due diligence was necessary:

[34] [The applicants explain that] … the firm was responsible for filling out the immigration forms. We provided them information and they completed the forms on their computers. We had no reason to believe that there was anything amiss with the work they were doing … As a result, when we signed the CSQ application form, we believed that they were properly completed …

[38] Of course, trust is a perfectly understandable attitude, especially when the contractor is chosen because of his expertise. Nevertheless, the diligent prospective immigrant must at least make sure of the validity of the information transmitted to the prospective host country, learn more about the consultant and make regular follow-ups.

[39] In this case, the applicants have degrees and hold jobs in the health care field. In addition, they all have e-mail addresses, meaning that they have access to internet. They therefore have the necessary resources to learn about the immigration process in Quebec and are able to follow up the work done by the consultant.

The TAQ judge applies the same criteria of due diligence to another couple’s evidence who kept checking the status of their application online and revised their application by indicating the name of the consultant once it was submitted by the consultancy firm. He determines that the couple is credible and has demonstrated diligent conduct and reverses the negative decision in favour of that couple (SAS-M-274662-1805).

7 Discussion and conclusion

The influence of courts on matters concerning immigration is an ongoing and important debate. Immigrants in liberal democracies, even when they acquire citizenship, need to adhere to certain rules to maintain their legal status and to reunite with their families (Bonjour and Block, Reference Bonjour and Block2016). They need to navigate a complex administrative and legal terrain for access and belonging that birthright citizens are often not required to do (López, Reference López2021; Gaucher, Reference Gaucher2018). Even though immigrants have limited rights in the political landscape, some scholars argue, justice organisations can have a transformative role and advance migrants’ rights (Joppke, Reference Joppke1998; Guiraudon, Reference Guiraudon, Bommes and Geddes2000; Basok and Carasco, Reference Basok and Carasco2010). According to this perspective, despite the restrictive approach of political actors, court judges strive to defend universal rights and drive migrants’ rights in an expansionist direction. In this article, we tested this assumption by examining how administrative tribunal judges decide appeals by migrants regarding negative determinations on permanent residency acquisition and family reunification in Canada’s province of Quebec.

Our findings raise doubts about the possibility of expanding migrants’ rights through a powerful institution of administrative justice, namely administrative appeals. We conclude that administrative adjudication does not constitute a venue through which tribunal judges strive for universal rights. By doing so, we join researchers that question the expansionist attitude of court and tribunal judges regarding migrants (Johannesson, Reference Johannesson2018; Ellermann, Reference Ellermann2013; Bonjour, Reference Bonjour2016). These studies illustrate the importance of judges’ role conceptions (Johannesson, Reference Johannesson2018), the role of political actors who can amplify some court rulings by selective and expansive interpretation (Bonjour, Reference Bonjour2016) and who can imbue their policy preferences to the policy design and subsequent iterations (Ellermann, Reference Ellermann2013).

While we cannot speculate on the views TAQ judges individually hold regarding their decision-making powers or their role within the policy process, our analysis of grounds for decisions allows us to make some important observations. First, we found that most appeal decisions are negative, and two-thirds of decisions concern the question of inadequacy of income. We observe that TAQ judges mostly validate the bureaucratic treatment of immigration. The application of strict restrictions to the sponsorship of family members and support obligations illustrate the state push for the self-sufficient migrant (Gaucher, Reference Gaucher2018). In appeal decisions, there does not seem to be an explicit focus to expand migrants’ rights.

Second, TAQ judges seem to have a narrow conception of their role within the policy process. In their analyses, TAQ judges limit their analyses to whether the bureaucratic decision was well-founded in fact and law or not. The following decision excerpt is revelatory in the sense that it illustrates how TAQ judges institutionally limit their discretion. Rather, the emphasis seems to be on the consistency of practice:

[29] As the Court of Appeal and the Superior Court have already indicated, the Tribunal has the same powers and discretion as the initial decision-maker when it is called upon to challenge a decision.

[30] At the same time, the Tribunal notes the absence of an administrative practice governing the exercise of this discretion or, at least, the absence of evidence that such a practice exists (2020 QCTAQ 01837).

In the light of previous research that looked at how law, particularly statutory protections provided by law, shapes how tribunal judges make decisions (Schreckhise et al., Reference Schreckhise, Chand and Lovrich2018; Chand and Schreckhise, Reference De and Schreckhise2020), this narrower understanding of their role by TAQ judges seems to be counterintuitive. As explained above, during the first few years of the tribunal’s existence, up until 2003, TAQ judges had a more expansive role conception as they emphasised the importance of preventing the wrongs that can result from an overly rigid adjudication approach. One could have expected a more expansive approach after 2005 as TAQ judges obtained tenure and judicial office protections, this has not been the case.

Finally, we documented that in less than 3 percent of cases immigrants won their appeals. We showed that in these positive decisions, TAQ judges take into consideration the personal circumstances of the appellants. That said, immigration rules that they are applying, especially regarding income regulations, do not appear to allow much room for reconsideration. Unlike other administrative appeal cases, such as whether an asylum seeker has a fear of persecution, or whether a migrant should be detained, the types of cases TAQ judges hear and the rules that govern them appear to be less amenable to interpretation.

The fact that our analysis is based on almost all immigration appeal decisions rendered by TAQ judges over a twenty-three-year period is one of the principal strengths of this study. In that sense, we examine almost the whole population of cases rather than a limited sample. The limitations of this study are the following. First, our analysis is based on actual appeal decisions. It is possible that some meritorious applicants have not filed appeals. Second, while we have no reason to doubt the reliability of the public database from which we downloaded immigration appeal decisions, we might have missed some decisions. Third, we cannot make assumptions regarding the quality of the first instance bureaucratic decisions or the appeal files.

We suggest three possible research areas that will expand this study. First, researchers can examine how TAQ judges ‘hear’ the appellants. They can look at the processes through which TAQ judges direct and shape the administrative hearing (Tomkinson, Reference Tomkinson2018; Lens, Reference Lens2012) as well as how responsive they are to the appellants’ needs (Portillo, Reference Portillo2017). Another line of research, through a survey or interviews, can try to capture the role conceptions of TAQ judges, the administrative justice values they prioritise as well as what shapes them. For example Schreckhise et al. (Reference Schreckhise, Chand and Lovrich2018) indicated that seniority and socialisation could play a role as they found younger tribunal judges were less likely to underscore their decisional independence. A final avenue for research could be looking at the judicial review role of the Quebec Superior Court. While migrants wishing to become permanent residents in Quebec cannot appeal rejections of their applications for a QSQ, they can challenge these decisions through judicial review.Footnote 18 This inquiry can potentially illustrate judges’ divergent approaches to judicial review (Miaz and Achermann, Reference Miaz and Acherman2021; Rehaag, Reference Rehaag2012) and how they view administrative justice.

Funding

This research is funded by Centre de recherche interdisciplinaire sur la diversité et la démocratie and Équipe de recherche sur l’immigration au Québec et ailleurs.