More than ever, in a context of growing diversity within societies, there is an urgent need for religious toleration. In the literature, some arguments for (religious) toleration are identified as being epistemic in nature. However, a proper analysis of epistemic arguments for religious toleration and a systematic account of their different types are still lacking. In contemporary discussions, when epistemic arguments are scrutinized, they are commonly equated with fallibilism, more precisely with John Stuart Mill's. For example, Brian Leiter writes that epistemic ‘arguments find their most systematic articulation in the work of John Stuart Mill’ (Leiter (Reference Leiter2013), 19). This leads him to state that epistemic arguments ‘ultimately [rest] on moral considerations’ (ibid., 15) because they take their value from ‘the contribution that [truth] makes to the morally valuable end of utility’ (ibid., 19). However, this is not true of all types of epistemic arguments. In the case here discussed by Leiter, toleration is instrumentally valuable to the quest for truth, but even if we accept this characterization of toleration as a truth-conducive fallibilism, it does not imply that all epistemic arguments are merely instrumentally valuable.

In this article, I provide a much-needed analysis of epistemic arguments for religious toleration and a systematic account of their different types that will help future work on epistemic arguments to be more precise and nuanced in answering questions concerning their value, their motivational potential, whether or not they ultimately rely on moral claims, whether or not epistemic arguments can meet the requirements of public reason, and so on.

The framework

In the literature, numerous definitions of toleration are offered. Toleration is sometimes defined with six conditions (Nicholson (Reference Nicholson, Horton and Mendus1985); Dilhac (Reference Dilhac2014) ), and even eight (A. J. Cohen (Reference Cohen2004) ). However, the following three components – disapproval (objection component), the power to interfere, and restraint (acceptance component) – are shared by all definitions and constitute an essential core of conditions to descriptively qualify as toleration. This descriptive form of toleration is neutral; it is ‘neither good nor bad’ (P. T. King (Reference King1998), 39) because it does not include limits, i.e. the separation of what should be tolerated from what should not. An act of toleration is not necessarily good; tolerating sexual harassment is bad, but tolerating religious diversity is good. Thus, in addition to those descriptive conditions, ‘moral or political toleration . . . will specifically incorporate limits to what should be tolerated so that any act of toleration will be either good or bad’ (A. J. Cohen (Reference Cohen2004), 95). However, since the purpose of this article is to classify types of epistemic arguments, it does not have to address the limits of toleration, and thus, this article will focus on the descriptive form defined with the three conditions detailed in the following lines.

The tolerant individual first needs to disapprove the practice or the belief in question. This condition is necessary to distinguish toleration from indifference. The disapproval doesn't need to be of a certain type nor to create an emotional response; the only condition is that those judgements have to be reasons not to tolerate (Dilhac (Reference Dilhac2014), 10). The disapproval is a reason to interfere with the practice. That reason is also called the objection component (P. T. King (Reference King1998), 44).

Second, the tolerant individual needs to believe that she has some power to interfere with the objected practice. It would be unfitting to call tolerant someone who believes she has no power to interfere with her neighbour's prayer of which she disapproves. That person is suffering or enduring her neighbour's practice but not tolerating it. It is worth noting that we always have, in democratic societies, a certain power to ask the political power to intervene. As Nicholson notes: ‘[i]n politics, in fact, everyone does have at least some power’ (Nicholson (Reference Nicholson, Horton and Mendus1985), 161). Further, the power does not have to be political, nor legitimate. The requirement is quite minimal; it would be enough for one to count as tolerating her neighbour if she knows that she can call the police or some other state agent to complain, but does not.

Third, the tolerant individual needs to see herself as having a reason not to interfere with the opposed practice. That reason is also called an acceptance component (P. T. King (Reference King1998), 51). Despite the paradoxical appearance, an individual can be called tolerant precisely when she has a reason to interfere, believes she has the power to interfere, but has a prevailing reason to refrain.

Religious toleration is the tolerance of religious acts, beliefs, practices, and so on. It is when the object of toleration is religion or religiously related. Religious toleration can, but does not have to, be supported by religious reasons or beliefs.

Since what differentiates toleration from intolerance is a prevailing acceptance component that prevents someone from acting on her opposition component, an argument for toleration will be successful when, in the weighing of reasons, the acceptance component prevails on the opposition component. An epistemic argument for toleration will accordingly aim to show that, because of epistemic reasons (i.e. reasons concerning the properties of beliefs or knowledge, or related issues), an acceptance component prevails on the objection component. This can be done either in giving epistemic reasons not to interfere with the objected belief or practice, or in reducing the force of the objection component for epistemic reasons so that a more minimal acceptance component – epistemic or not – might prevail.

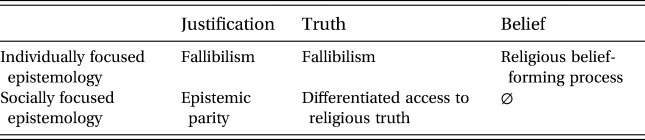

In the sections that follow, I analyse and classify in four different types the different epistemic arguments that we can find in the literature. I name those four types fallibilism, religious belief-forming process, epistemic parity and differentiated access to religious truth or divine message. Further, I suggest that we can provide a tentative systematic organization, or a mapping, of those around the standard epistemic notions of justification, truth, and belief in combination with a distinction of the chosen epistemological approach – whether individually or socially focused. Table 1 offers a visual representation of the proposed account.

Table 1 Systematic organization of the different types of epistemic arguments for religious toleration

One further contribution of this mapping is that we can clearly see that a logical space is still unexplored in issues related to belief with a socially focused epistemological approach, which offers new possible avenues.

Fallibilism

Following Charles Sanders Peirce, fallibilism can be conceived as a mean between two extremes: dogmatism and scepticism (Dougherty (Reference Dougherty, Bernecker and Pritchard2011), 131). While the dogmatic never questions a knowledge attribution, the sceptic never allows such attribution. According to Trent Dougherty, the epistemic doctrine of fallibilism ‘is about the consistency of holding that humans have knowledge while admitting certain limitations in human ways of knowing’ (ibid.).

In other words, a theory of fallibilism always considers the inference of the truth of p from a reason r – concerning propositions of fact – as inductive and uncertain; we cannot deduce the truth of p from a reason r. Mathematical propositions escape that problem because their truth is established by deduction, not induction. We can have a strong justification of a proposition of fact p and be subjectively and intersubjectively convinced of its truth, but there will always remain a possibility of error. That possibility of being mistaken is the thesis of fallibilism. Fallibilism is largely accepted in epistemology (S. Cohen (Reference Cohen1988), 91). Fallibilism can concern the truth enquiry or the justification itself.

Applying fallibilism to the religious domain can have desirable consequences; it can avoid dogmatism without having to abandon the possibility of religious knowledge or true and/or justified religious beliefs.Footnote 1 An advantage of the fallibilist type of argument for toleration – which presents one's fallibility as an acceptance component – is the potential easy acceptance of it by the individual holding religious beliefs since it does not fundamentally call into question the truth value of her beliefs. It only requires a small doubt, a mere recognition of one's fallibility in one's truth enquiry or justification. There is no confrontation in the substance of beliefs, but only on the level of credence in those beliefs. For example, for an agent, recognizing the fallibility of her belief in life after death only implies recognizing that one might be wrong. Any degree of credence below certainty qualifies as fallible.

The basis of every fallibilist argument for toleration is that any justification or truth enquiry concerning questions of fact is fallible, i.e. there always remains a possibility of error. Building on that premise, one can construct acceptance components in two ways. First, one can argue that a free market of ideas is necessary to find the truth and to progress in our human knowledge. In other words, given our fallibility, toleration is a truth-conducive practice in that it increases the likelihood to be in the truth and to avoid error, and this is a reason not to interfere with the beliefs with which one disagrees. Second, one can argue that, given human fallibility, we never have the required certainty to justifiably impose our beliefs to others nor to censor contrary opinions. These provide reasons not to interfere with the disapproved beliefs.

Toleration as a truth-conducive practice

This first version, that toleration is a truth-conducive practice, is probably the most well known and is often what is understood to be the epistemic argument for toleration par excellence. This argument was formulated by John Stuart Mill in the second chapter of On Liberty (Mill (Reference Mill, Bromwich and Kateb2003 [1859]). According to Mill, because of our fallibility, we can never be sure that our opinions are true. The most certain opinions we have are those exposed to critical examination by others: ‘The beliefs which we have most warrant for, have no safeguard to rest on, but a standing invitation to the whole world to prove them unfounded’ (Mill (Reference Mill, Bromwich and Kateb2003), 91). Further, as Leiter claims, this argument from Mill is not limited to the toleration of beliefs, because, especially for moral claims, seeing different practices and their consequences is necessary to the truth enquiry. As Leiter puts it: ‘to know how we really ought to live, it is not enough to hear differing opinions expressed on the subject; one must have the empirical evidence provided by lives actually lived in accordance with different guiding principles’ (Leiter (Reference Leiter2013), 21). Thus, the confrontation of ideas and practices is necessary to know when opinions are false, to complete them when they are partially true, and to have confidence they are true. In other words, free discussion and freedom of practices, which are made possible by toleration, are truth-conducive practices, i.e. they raise the likelihood to reach truth and avoid error, hence enhancing an individual's truth enquiry.

Lack of certainty for intolerance

William Walwyn, in The Compassionate Samaritane (Reference Walwyn and Wootton2003 [1644]), and John Locke, in A Letter on Toleration (Reference Locke and Shapiro2003 [1689]), offered a rebuttal of the justification of intolerance by love, that is, when people knowing the truth impose it on others who refuse to recognize it. This kind of intolerance is called ‘by love’ because it aims at a greater good. As part of their arguments, Walwyn and Locke grant the possible legitimacy of such intolerance by love but claim that this would require an absolute certainty, which no one has. As Walwyn puts it: ‘since there remains a possibility of error, notwithstanding never so great presumptions of the contrary, one sort of men are not to compel another, since this hazard is run thereby, that he who is in an error may be the constrainer of him who is in the truth’ (Walwyn (Reference Walwyn and Wootton2003), 250).

Locke offered a famous argument for toleration based on the separation of the Church and the state. One of the reasons offered for it relies on fallibility. Locke maintained that the magistrate, or the civil government, has no legitimate authority in religious matters because this position does not grant him an epistemic superiority in religious matters. He is still fallible, as anyone else is: ‘neither the care of the commonwealth, nor the right of enacting laws, does discover this way that leads to heaven more certainly to the magistrate, than every private man's search and study discovers it unto himself’ (Locke (Reference Locke and Shapiro2003), 229). Princes have no right to decide for their subject nor the epistemic superiority to identify with certainty the true religion: ‘Neither the right, nor the art of ruling, does necessarily carry along with it the certain knowledge of other things; and least of all of the true religion’ (ibid., 230). Since everyone is fallible, the choice of religion has to be made by each individual in her conscience. In sum, Walwyn and Locke argued that we can never have the certainty or the justification that would be required to legitimately impose our religious views on others.

Mill similarly argued that we never have the certainty that would be required to censor an opinion. According to Mill, we are not justified in censoring an opinion unless we are certain that it is false. Justified censorship would require an epistemic certainty, but no one has this certainty. Accordingly, we should not censor any opinion because ‘if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility’ (Mill (Reference Mill, Bromwich and Kateb2003), 118). Censorship is an assumption of infallibility because in deciding on the falseness of a proposition for everyone else, you assume your infallibility. This is never justified.

Thus, the recognition of one's fallibility can serve as a reason not to interfere with the objected beliefs either because a variety of opinions and practices is truth-conducive or because we do not have the certainty that would be required to justifiably censor false opinions or to justifiably impose what we take to be truth on others. In the proposed mapping, fallibilism belongs to two categories: individually focused truth (toleration as a truth-conducive practice) and justification (lack of certainty for intolerance).

Religious belief-forming process

The arguments for toleration relying on the religious belief-forming process are based on the properties of an individual's beliefs. More precisely, they are based on the doxastic involuntarism thesis, which claims that it is impossible to believe at will. Believing is a propositional attitude that consists in taking a given proposition to be true. To understand what is meant by believing ‘at will’, we can distinguish, following Pamela Hieronymi (Reference Hieronymi2006), between constitutive reasons and extrinsic or practical reasons for believing. A constitutive reason is a reason that bears on whether p; in other words, a constitutive reason is a reason why a proposition is true. Extrinsic or practical reasons are reasons why it would be advantageous or good to hold a particular belief. For example, if someone offered you money to believe something that you know to be false, you may have an extrinsic reason to believe it (the monetary reward), but you have no constitutive reason for its truth. In order to be able to believe at will, ‘one would have to be able to believe for extrinsic reasons’ (Hieronymi (Reference Hieronymi2006), 52).

The doxastic involuntarism thesis claims that one cannot form beliefs at will, i.e. for extrinsic reasons, and that beliefs are formed only in response to intrinsic reasons, i.e. reasons bearing on the truth of a proposition. Applied to religious toleration, it can be argued that persecution and threats merely give extrinsic reasons, and thus are unable to change beliefs.

From the premise that one has no direct control over her beliefs, we find two general strategies of argumentation in the literature. First, Pierre Bayle and John Locke argued that the use of persecutions and violence to change religious beliefs is irrational and ineffective, and that, accordingly, it should be abandoned. The impossibility to constrain beliefs is then presented as a reason not to interfere with the disapproved religious practices. Second, one could claim, against epistemic deontologists,Footnote 2 that one cannot be blamed for one's beliefs because one can only be blamed for what is under one's control and beliefs are not under an agent's direct control. Accordingly, since religious beliefs are not under one's control, one should not be blamed nor persecuted for her beliefs. Walwyn offered an argument along those lines arguing that individuals should never be punished for their beliefs because punishment is solely the recompense of voluntary actions.

Ineffectiveness of persecution

According to Jean-Fabien Spitz, Locke's argumentation in A Letter Concerning Toleration shows less the illegitimacy of coercion in religious matters than its irrationality (Spitz (Reference Spitz and Locke2007), 14). It is irrational because the state has no power in the spiritual jurisdiction; persecutions are unable to constrain beliefs, which is what ultimately matters. Locke's argument relies heavily on the religious belief-forming process to show that persecution will never produce its alleged intended goal. The first step in Locke's argument is to underline the true nature of religion: ‘All the life and power of true religion consists in the inward and full persuasion of the mind; and faith is not faith without believing’ (Locke (Reference Locke and Shapiro2003), 219). In doing so, he emphasizes the importance of sincere individual belief; inner persuasion is indispensable to pleasing God. Mere adherence to a religious system and rituals will never replace individual beliefs.

Locke maintains that religious beliefs can never be coerced. One can be coerced to perform actions, but not to believe. According to Locke: ‘It is only light and evidence that can work a change in men's opinions; and that light can in no manner proceed from corporal sufferings, or any other outward penalties’ (ibid., 220). This is due to the nature of our understanding, which ‘cannot be compelled to the belief of any thing by outward force’ (ibid., 219).

In sum, Locke argues that beliefs can only be formed or changed by constitutive reasons – reasons related to the truth or the falseness of a proposition – and that other extrinsic reasons – for example, the desire to avoid or to be delivered of a multitude of suffering inflicted by persecutors – will never be able to change beliefs directly. This impossibility of intolerance of beliefs constitutes an acceptance component for the tolerance of disapproved religious practices. As stated by Spitz, the heart of the reasoning of the Letter Concerning Toleration is that: ‘our thoughts are not within our power. Jointed with the conviction that, concerning religion, only sincerity saves, it constitutes the foundation of the Lockean conception of tolerance’ (Spitz (Reference Spitz and Locke2007), 15, my translation).

In De la tolérance: commentaire philosophique (Bayle (Reference Bayle and Gros2014) [1686]), Bayle also insists on the importance of beliefs in religion saying that: ‘all external Acts of Religion . . . are approv'd by God only in proportion to the internal Acts of the Mind from whence they proceed’ (Bayle (Reference Bayle, Kilcullen and Kukathas2005), 76). In other words, it is impossible to offer an exterior act of adoration that pleases God without being in adoration in one's soul, i.e. when thoughts and beliefs are in accordance with the exterior acts. Concerning religion, Bayle thus insists on judgements that our spirit forms about God rather than on exterior rites. Persecution and coercion can only force someone to perform acts, but it cannot create persuasion of the soul. Bayle thus concludes that it is impossible that the use of persecution may be an appropriateFootnote 3 means of conversion because it is unable to create the desired goal.

To inspire religion, ‘All that ought to be done in this case is instructing ’em, but without any Violence or Constraint’ because ‘Religion is a matter of Conscience subject to no control’ (ibid., 213–214).Footnote 4 Beliefs respond to truth only, and if they do not, no physical coercion will help: ‘every Heretick accepts the Truth, provided he knows it, and as soon as he knows it, but not otherwise nor sooner; for so long as it appears to him a hideous Grotesque of Falshood and Lye, so long he is not to admit, he is to fly and detest it’ (ibid., 232). If a person is convinced of the truth of her religion and wants to spread it, she must do it only through instruction and argumentation. In other words, she cannot spread her belief except by constitutive reasons, and never by practical extrinsic reasons with the use of violence.

The epistemic argument is thus that religious beliefs can never be formed by force nor by coercion; consequently, we ought to give up the use of violence to make conversions. Trying to impose a belief with force, as Walwyn (Reference Walwyn and Wootton2003, 265) points out, makes the persecutor suspect on epistemic grounds. When a person uses force to try to impose a belief, we might suspect she is not trying to spread truth, but something else because truth does not need external force to impose itself on someone.

It might appear that Locke and Bayle undermine the power condition, and thus that they are not arguing for toleration as conceptualized in this article, but rather for the impossibility of intolerance of disapproved beliefs. However, as I see it, Locke and Bayle are not arguing for toleration of beliefs (because it is impossible to coerce belief), but they argue for the toleration of practices on the basis of the impossibility of belief coercion (because of the belief-formation process).

No punishment for what is involuntary

In his text of 1644, Walwyn first states that no one chooses her beliefs, i.e. that belief formation does not respond to the will. He wrote: ‘Because of what judgement soever a man is, he cannot choose but to be of that judgement’ (Walwyn (Reference Walwyn and Wootton2003), 249). This is so obvious to him that he does not argue for it and supposes that everyone will grant him that fact. Beliefs are necessities that escape the power of will. When reason has examined the facts and the relevant considerations, judgement happens without any involvement of the will: ‘Whatsoever a man's reason does conclude to be true or false, to be agreeable or disagreeable to God's Word, that same to that man is his opinion or judgement, and so man is by his own reason necessitated to be of the mind he is’ (ibid.).

Walwyn argues that what falls not under the control of the will (and thus is a necessity) ought not to be punished, because punishment can only be attributed to voluntary actions: ‘Now where there is a necessity there ought to be no punishment, for punishment is the recompense of voluntary actions’ (ibid.). Following this argument, we arrive at the conclusion that a person ought not to be punished or persecuted for her judgements or beliefs. Intolerance is here considered as punishment for disapproved belief. Even if she is really erring, she should not be punished for that. The involuntariness of beliefs thus constitutes a reason to give up retribution – which would be a form of interference – for disapproved beliefs.

Epistemic parity

The first two types of epistemic argument for religious toleration were based on individual doxastic attitudes, and that is what epistemology has traditionally focused on (Goldman & Blanchard (Reference Goldman, Blanchard and Zalta2016) ). The following two types take a social perspective and consider the impact of others’ beliefs on the status of one's beliefs. More precisely, they consider the impact of religious diversity on justification and truth. In this section, I explore arguments that rely on justification issues, and in the next section, I will explore arguments that rely on issues around truth.

The notion central to the arguments of this section is epistemic peer disagreement. We can adopt the following working definition of an epistemic peer: ‘Roughly speaking, an epistemic peer is someone who is equivalently aware of the details of an issue, and equivalently capable of evaluating those details’ (Kraft (Reference Kraft2012), 72). What happens then when two epistemic peers disagree? More precisely, what does rationality require when one disagrees with someone whom one regards as one's epistemic peer? Multiple answers are offered in the literature for the appropriate response to epistemic peer disagreement. Those answers can be placed on a spectrum between conformist and nonconformist views. Depending on where one situates oneself, different arguments for toleration are available.

According to the nonconformist view,Footnote 5 ‘one can continue to rationally believe that p despite the fact that one's epistemic peer explicitly believes that not-p, even when one does not have a reason independent of the disagreement itself to prefer one's own belief’ (Lackey (Reference Lackey, Callahan and O'Connor2014), 300). Accordingly, there can be a reasonable disagreement between epistemic peers. Many reasons are offered why one can be justified in holding to one's belief, but the reason that might be helpful for toleration is that ‘a single body of evidence can rationalize more than one doxastic attitude’ (Goldman & Blanchard (Reference Goldman, Blanchard and Zalta2016) ). It is thus possible that two individuals rationally form contradictory beliefs from the same body of evidence.

According to the conformist view, ‘unless one has a reason that is independent of the disagreement itself to prefer one's own belief, one cannot continue to rationally believe that p when one is faced with an epistemic peer who explicitly believes that not-p’ (Lackey (Reference Lackey, Callahan and O'Connor2014), 301). Accordingly, disagreement between epistemic peers is never rational; one of the two must have formed an irrational belief. Consequently, it can be argued that the two should abandon their beliefs, suspend judgement or, at a minimum, that the epistemic peers disagreeing about whether p ‘should subsequently become substantially less confident in their opinions regarding p’ (Goldman & Blanchard (Reference Goldman, Blanchard and Zalta2016) ). That lowering of justification can also lead to belief reassessment.

Difficulty of justification (nonconformist views)

In De la tolérance: commentaire philosophique, Bayle also offers an argument for toleration based on the difficulty of justification. This argument is found in his critique of the concept of orthodoxy; it is a rebuttal of the apology of just persecution, i.e. persecution by the orthodoxy against the heretics. According to Bayle, orthodoxy could not permit the limitation of the use of persecution to one group. Authorizing the orthodox to use violence against the heterodox or heretic is equivalent to authorizing the general use of violence of all against all, ‘because every Church believes to be the true one, it is impossible that it learns that God wants the true Church to practise certain things without believing in its conscience that it is obliged to practise them’ (Bayle (Reference Bayle and Gros2014), 286, my translation).Footnote 6 This would lead to the absurd conclusion of generalized violence. According to Bayle, if God authorizes the orthodox to do something, he authorizes by the same token every church to do the same because the only mark of orthodoxy in humans is the conscience which is the same in everyone, orthodox and heretics alike.

The concept of orthodoxy, from an epistemological standpoint, is impracticable because it is impossible to evaluate, from an independent point of view, who the orthodox really is. In evaluating orthodoxy, everyone starts with the hypothesis that she knows the truth; it is, according to Bayle, begging the question: ‘everyone will use the dictionary as one wills, starting with this hypothesis, I am right and you are wrong’ (ibid., 270, my translation, emphasis in French).Footnote 7 It follows that the epistemic parity cannot be defeated from the inside and no one has a privileged view on the object of the disagreement (the orthodoxy of the different religions) outside the disagreement itself. This argument from epistemic parity allows Bayle to refuse a privilege to one religion in particular on the ground of orthodoxy. Bayle maintains that the orthodox/heterodox distinction is impracticable and that everyone should rather give up the use of persecution in a common agreement. Locke also develops a similar argument, but it is less articulated.

In Political Liberalism (Reference Rawls2005), John Rawls also relies on a form of reasonable disagreement. However, the epistemic argument in Rawls does not directly justify a principle of toleration; it rather grounds the need to move the justification of toleration from comprehensive doctrines to the political realm.

According to Rawls ‘reasonable disagreement is disagreement between reasonable persons’ and reasonable persons, ‘[g]iven their moral powers of thought and judgment: they can draw inferences, weigh evidence, and balance competing considerations’ (Rawls (Reference Rawls2005), 55). Reasonable disagreement is not caused by an asymmetry of intellectual faculties or of epistemic competency, nor by a lack of liberty, nor by a lack of discussion, but by intrinsic difficulties of certain judgements; Rawls calls those difficulties the burdens of judgement. Rawls identifies six burdens of judgement but does not claim the list to be exhaustive. In this list, we find, among others, the complex and conflicting nature of evidence, and the complexity and indeterminacy of concepts. Concerning the latter, Rawls writes: ‘To some extent all our concepts, and not only moral and political concepts, are vague and subject to hard cases; and this indeterminacy means that we must rely on judgment and interpretation (and on judgments about interpretations) within some range (not sharply specifiable) where reasonable persons may differ’ (ibid., 56).

In other words, because of the burdens of judgement, it is possible that two different persons reasonably form conflicting beliefs from the same body of evidence. We are thus often in a situation of underdetermination or indeterminacy of evidence. This is a pervasive problem in politics that should be taken into account: ‘we are to recognize the practical impossibility of reaching reasonable and workable political agreement in judgment on the truth of comprehensive doctrines, especially an agreement that might serve the political purpose, say, of achieving peace and concord in a society characterized by religious and philosophical differences’ (ibid., 63). In sum:

reasonable persons see that the burdens of judgment set limits on what can be reasonably justified to others, and so they endorse some form of liberty of conscience and freedom of thought. It is unreasonable for us to use political power, should we possess it, or share it with others, to repress comprehensive views that are not unreasonable. (ibid., 61)

Since the rules governing the shared life of free and equal citizens have to be susceptible (at least in principle) to the agreement of all, those rules ought not to be grounded on a particular comprehensive doctrine. Those rules should be political, i.e. independent of every comprehensive doctrine, in order to be the potential object of a consensus. The toleration principle that could be the object of such a consensus in the original position is equal liberty of conscience: ‘Now it seems that equal liberty of conscience is the only principle that the persons in the original position can acknowledge’ (Rawls (Reference Rawls1999), 181). On Rawls's account, the epistemic argument does not directly ground toleration, but it justifies the need to move to a political justification of a toleration principle that could be accepted by all. On the other hand, we could also see Rawls as offering a counterargument, based on the difficulty of justification, to the use of political power to limit the liberty of conscience in favour of a particular comprehensive doctrine. The reasonable disagreement thesis would then be used to reduce the force of an objection component.

Epistemic humility (conformist views)

In an article entitled Religious Diversity and Religious Toleration (Reference Quinn2001), Philip Quinn formulates an original argument for toleration based on what he calls epistemic humility. Epistemic humility is a conformist response to epistemic peer disagreement, i.e. it involves a lowering of justification of (or of confidence in) beliefs of the parties involved in the disagreement. Further, Quinn assumes that in the absence of a tiebreaker, religions should be considered epistemic peers.Footnote 8 Quinn's aim is to reduce the force of the religious objection component so that a moral acceptance component might be more justified and thus prevail on the objection component: ‘The strategy involves attempting to establish that moral principles which support toleration have a higher epistemic status than conflicting religious claims which support intolerance’ (Quinn (Reference Quinn2001), 76).

Quinn adopts the following principle inspired by Kant and Bayle: ‘The epistemic credentials of two conflicting claims are to be assessed and then compared. The applicable epistemic principle is that, whenever two conflicting claims differ in epistemic status, the claim with the lower status is to be rejected’ (ibid., 70). He grants that religious beliefs – and religious beliefs supporting intolerance – might be well justified. However, when one seriously considers religious diversity and the disagreement between religions, one should adopt a conformist attitude and lower the justification of all one's religious beliefs. As Quinn writes: ‘Thus, absent a special reason to think otherwise, I shall assume that religious diversity has a negative epistemic bearing not only on the beliefs that are outputs of [Christian practice] but also on other parts of the total system of Christian belief and that the same goes for rivals’ (ibid., 64).

By adopting a conformist view and consequently lowering the justification of all religious beliefs, religious beliefs supporting intolerance will also be less justified. If we suppose that individuals facing different possibilities of action will choose the one that is more justified, the hope is that the awareness of religious diversity will reduce religious intolerance and foster acting on a moral principle of tolerance that is better justified. Thus, ‘[r]eligious diversity thus both creates the need for toleration and contributes to its epistemic grounds’ (ibid., 77).

Building on Quinn's concept of epistemic humility, James Kraft (Reference Kraft2006; Reference Kraft, Kraft and Basinger2008) and David Basinger (Reference Basinger, Kraft and Basinger2008) also offered other arguments for toleration. In his 2006 article, Kraft wanted to use ‘developments in externalist epistemology and philosophy of mind as a foundation for a tolerance-producing attitude of epistemic humility towards the beliefs one retains in light of religious diversity’ (Kraft (Reference Kraft2006), 101). According to Kraft, the level of detail that our faculties can resolve ‘is insufficient to rule out competing beliefs’ (ibid., 106). This incapacity would offer a foundation for the thesis of epistemic parity.

For Basinger, religious pluralism within society is not necessary for epistemic humility; religious disagreement in the midst of a single religion is sufficient. On Basinger's account, the proper response to religious peer disagreement is to engage with our peers in belief assessment.

The result of this ‘epistemically humbling’ acknowledgement is not normally that the proponents of the differing perspectives abandon their positions. . . . However, . . . the respect that a proponent of a given perspective in a religious dispute has for her competitors increases in proportion to the extent to which she comes to believe that her competitors are in fact equally knowledgeable and sincere (are not in fact ignorant or evil). (Basinger (Reference Basinger, Kraft and Basinger2008), 37–38, emphasis in original)

This new respect for the other would reduce the objection component and could also offer an acceptance component.

Differentiated access to religious truth or divine message

In philosophy of religion, responses to or attitudes towards religious diversity are typically classified using the tripolar typology of exclusivism, inclusivism, and pluralism (Schmidt-Leukel (Reference Schmidt-Leukel and Knitter2005) ). Those categories can be applied to a variety of objects: salvation, truth, morality, and so on. They should not be understood as uniform categories but rather as families of positions, for example numerous positions can fall under the ‘pluralist’ label. To introduce the typology, we can first apply it to the issue of salvation in the face of religious diversity. The salvation exclusivist will claim that only one religion, most likely hers, provides a way to salvation. On the contrary, the salvation pluralist will claim that more than one religion can provide a way to salvation and that no religion is superior in its salvific means, that they are peers in their salvific capacities. The salvation inclusivist will try to hold a middle ground and argue that while more than one religion can provide a way to salvation, one provides a better or a superior way.

Responses to religious diversity that are relevant here for the epistemic arguments for toleration concern the access to divine message or to true religious beliefs. Robert McKim (Reference McKim2012) formulates different possible versions of exclusivism about truth. The first one he considers is the strongest: ‘Our tradition is entirely right, and all other traditions are entirely wrong’ (McKim (Reference McKim2012), 14). However, this formulation does not account for the overlap of beliefs, i.e. beliefs shared by two or more religions – as is the monotheist belief that ‘God is one’. Now, it does not follow that we need to reject exclusivism, but we need to specify its definition. A more nuanced version would be the following:

The claims of our tradition are true, or most of them are true, and in all respects we do best in terms of truth; other traditions are correct when they accept our true claims; and they are mistaken when they reject our true claims; and their claims are generally mistaken. (ibid., 28)

Another formulation of exclusivism about truth is formulated by Nathan L. King:Footnote 9 ‘the doctrines of the home religion are true, doctrines incompatible with these are false, and there are no religious truths to be found only outside the home religion’ (N. L. King (Reference King2008), 834). Every formulation presented here refers to the truth of doctrines or beliefs. However, it would be advantageous to formulate it in terms of access to religious truth or to true religious beliefs. This access can be understood as a channel of information coming from the transcendent Being(s) or the divine. It would account for the overlap of beliefs and would allow a given religion to have false beliefs without having to renounce its exclusivism about truth. Indeed, false beliefs do not question the exclusive access. A religion could contain only a small number of true beliefs, but still have an exclusive access to religious truth. I thus suggest the following definition:

Exclusivism about truth: Only one religion R* has unique access to religious truth, true beliefs of other religions Ri can be said to be true only because they were imported from R*, and no religious truth can be found only outside R*.

The exclusivist will thus claim that only one religion has access to the unique channel. It means that every true belief that is in Ri is also in R* but since Ri has no access to religious truth, the true belief was imported from R*.

However, the exclusivist position, in terms of access or of propositions, faces important epistemic challenges. What might be the biggest difficulty for a definition in terms of access as the one suggested here is the possibility of a religion Ri having a true belief by chance, and not by importation from R*. In any case, defending exclusivism is not the purpose of this article. What we need for our purpose is a general idea of the different forms that exclusivism can take. The epistemic arguments regrouped here are all based on a rejection of some sort of exclusivism about truth.

At the other end of the spectrum of responses to religious diversity is pluralism about truth. It is important not to confuse pluralism with relativism, for many pluralists endorse a correspondence view of truth. According to N. L. King, the pluralists assert that all religions ‘are on par with respect to truth and epistemic access to Ultimate Reality’ and that accordingly ‘no religion is epistemically or alethically privileged’ (N. L. King (Reference King2008), 834). I thus suggest the following definition in terms of access:

Pluralism about truth: More than one religion has access to religious truth, but none has a privileged access.

In a pluralist perspective, it is possible that different religions capture different parts of the divine message, but what is important is that no religion can claim to have an epistemically superior access that would allow it to capture a truer or purer message than other religions. Some pluralists also claim that there is an underlying unity in all religions: ‘The pluralist approach to religious diversity embraces all the differences of the world religions thinking ultimately those differences get resolved in a unity’ (Kraft (Reference Kraft2012), 112). This unity could be the transcendent Being at the source of various revelations. However, the pluralist approach would have difficulty in grounding a principle of toleration since the objection component would be missing. To be sure, a pluralist could argue for peaceful cohabitation based on respect or some other principles, but it would not be toleration as defined above.

An inclusivism about truth will try to hold a middle ground between exclusivism and pluralism. Without denying possible access to religious truth for other religions, the inclusivist will still claim to have a privileged access. According to McKim, what differentiates inclusivism from exclusivism is the positive affirmation that: ‘Others do fairly well overall in terms of truth, and [that] we are only somewhat better off than they are in this regard’ (McKim (Reference McKim2012), 36). Further, other religions may hold true beliefs that the privileged religion R* does not (ibid., 37). Again, I suggest a definition in terms of access:

Inclusivism about truth: One religion R* has a privileged access to religious truth; other religions Ri may have a limited access to religious truth and can hold certain true religious beliefs that may only be found in Ri.

Thus conceived, the epistemic privilege may be that one religion receives the divine message with less ‘noise’ than others. This privileged access will assure an overall superiority, but when we consider each belief individually, the privileged religion could be in error while an unprivileged one may be correct.

An epistemic argument for toleration based on differentiated access to religious truth can construct an acceptance component from the issues presented in this section, or it can use them to reduce the force of the objection component so that, in the weighing of reasons, the acceptance component might prevail.

An inclusivist acceptance component

According to Khaled Abou El Fadl (Reference Abou El Fadl, Cohen and Lague2002), the Qur'an can ground a principle of toleration on verses that refer to the diversity of religion and of people as following from the will of God:

In one such passage, for example, the Qur'an asserts: ‘To each of you God has prescribed a Law and a Way. If God would have willed, He would have made you a single people. But God's purpose is to test you in what he has given each of you so strive in the pursuit of virtue, and know that you will all return to God [in the Hereafter], and He will resolve all the matters in which you disagree.’ (Abou El Fadl (Reference Abou El Fadl, Cohen and Lague2002), 17)

Since God gave a revelation of its own to other religions, non-Muslims can consider that they have a certain access to religious truth, though a limited one. Abou El Fadl goes the inclusivist way and carefully avoids going into pluralism. For him, other religions are not on par with Islam. Abou El Fadl maintains that Islam is superior in its access to truth, and also to salvation, making him also an inclusivist about salvation:

Although the Qur'an clearly claims that Islam is the divine truth, and demands belief in Muhammad as the final messenger in a long line of Abrahamic prophets, it does not completely exclude the possibility that there might be other paths to salvation. The Qur'an insists on God's unfettered discretion to accept in His mercy whomever He wishes. (ibid.)

Further, on Abou El Fadl's view, the inclusivist position is supported by the following verse: ‘“Those who believe, those who follow Jewish scriptures, the Christians, the Sabians, and any who believe in God and the Final Day, and do good, all shall have their reward with their Lord and they will not come to fear or grief”’ (ibid.). Though this inclusivist position can be found and grounded in the Qur'an, according to Abou El Fadl, it is still underdeveloped in Islamic theology. This provisional value given to other religions – their partial and limited access to religious truth and a potential access to salvation – can constitute an acceptance component, and thus ground toleration because even though they disagree, they still have some true beliefs.

Ibrahim Kalin (Reference Kalin, Neusner and Chilton2008) also offers an Islamic argument for the toleration of the People of the Book (Jews and Christians) on epistemic inclusivism grounds. Very summarily, according to Kalin, Muslims and the People of the Book worship the same one God who is the source of their respective revelations, but Muslims have a privileged access to religious truth, a purer message. Kalin thus invites Muslims to consider the limited access of the People of the Book and their underlying unity with Islam – they all claim Abraham as their father – as a reason to grant them religious freedom.

Rejection of exclusivism and reduction of the objection component

In a 2015 article, Dirk-Martin Grube offers an epistemic argument for toleration that has as its central concern a rejection of truth exclusivism. In doing so, Grube aims to reduce the objection component so that a minimal acceptance component may suffice to engage someone in toleration. Exclusivism about truth, or bivalence,Footnote 10 implies that what is different from one's religion, and not only what is directly contrary, is necessarily false and ought to be rejected. One does not need to examine the other's religious beliefs; they are necessarily false by implication of one's exclusivism. An exclusivist about truth will need a strong acceptance component to engage her in toleration because her objection component is also strong.

Further, that kind of exclusivism hinders dialogue and the encounter with the other, because ‘who would want to learn from falsity, who would consider alternative religious beliefs to be a serious challenge to his own if he knows that they are illegitimate or even false?’ (Grube (Reference Grube2015b), 468). As a solution, in order to foster serious interreligious dialogue, Grube suggests replacing the notion of truth with the notion of justification; truth is independent of the agent, but justification is agent-dependent and context-sensitive. The difference in justification can be perceived as legitimate, and there is thus a genuine opportunity to learn from difference: ‘justification being context-dependent and perspectival can be legitimately different, thus can be plural’ (ibid., 476, emphasis in original)

Seeing what is different as not necessarily false, but as potentially as justified as one's beliefs are can reduce the objection component and foster toleration:

If I do not consider a deviant (religious) belief to be illegitimate or false, my reasons for disagreeing with it will be less strong than under exclusivist or bivalent parameters. Thus, the pull to displace those deviant beliefs will be not as strong as under those parameters. Consequently, the countermeasures which are required for neutralizing it do not have to be construed as strongly as under those parameters. (ibid., 472)

Further, seeing the other as justified in her religious beliefs can also serve as an acceptance component that could prevail on an objection component that is reduced due to a rejection of an exclusivist view about truth.

Conclusion

In this article, I analysed a number of different epistemic arguments for religious toleration and regrouped them in four different types that I named fallibilism, religious belief-forming process, epistemic parity, and differentiated access to religious truth or divine message. I also offered a mapping of those different types of arguments using the standard epistemic notions of justification, truth, and belief coupled with a distinction of focus in the epistemological approach. Such analysis and organization will help properly identify what is at stake in each argument. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, a significant contribution of this mapping is that it allows us to see a possibly unexplored space for new epistemic arguments for religious toleration in taking a socially focused epistemological approach to belief. For example, inspired by research in sociology of religion, such an argument could mobilize some context-dependent properties of a religious belief-forming process as a reason to tolerate others that would have been socialized in different ways than we did.

Much is still to be done to have a proper evaluation of the value of epistemic arguments for (religious) toleration and their possible contribution, and I hope that the analysis and the mapping offered here will be helpful for future work on epistemic arguments for toleration and the articulation of new ones.Footnote 11