The year before her diagnosis, she was — “coincidentally and ironically,” she says — working as a lobbyist for such patient advocacy groups as Rethink Breast Cancer, where she was focused specifically on the issue of take-home cancer drugs for women under 65.

In addition, she was volunteering for the Ontario Progressive Conservative Party campaign in the run up to the 2018 General Election.

“I was going at 110 per cent so I really had no time to decompress and maybe feel [any] symptoms” that might have signalled something was wrong, she says.

Two months later, she underwent surgery to resect the tumour, which required a month of recovery, followed by radiation and a prescription for a take-home chemotherapy drug. And that’s when things got really challenging.

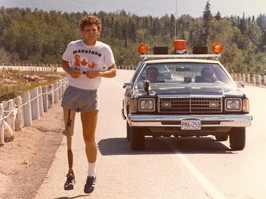

Rebecca Grundy after surgery for glioblastoma. “A CT scan showed a mass on the left frontal lobe of my brain about the size of my fist,” she says. SUPPLIED

In Ontario and Atlantic Canada, intravenous drugs given in hospital are covered, take-home drugs in pill form are not if you’re under 65, and not on social assistance. Since Grundy was 28 at the time, she had to rely on her private insurance to cover temozolomide, the only drug approved by the province for treatment of glioblastoma — coverage that soon ran out given the medication’s hefty $7,ooo per month cost.

“Unfortunately for me, I didn’t have a comprehensive plan,” says Grundy. “I only had $5,000 of drug benefits per year up to 80 per cent of the drug, and because my drug cost around $7,000 a month, that got eaten up quite quickly, of course. You’d think that, when there’s only one form of treatment, it would automatically be covered, but that’s not the case.”

9 minute read

9 minute read

![“Finally, [the treatments] get approved for funding and you think, amazing!” says MJ DeCoteau, founder and executive director of Rethink Cancer. “Only to realize you live in Ontario and you’re under 65.” SUPPLIED](https://smartcdn.gprod.postmedia.digital/healthing/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/image002.jpg?quality=90&strip=all&w=720&h=540)