Asian communities have been present in Canada since the 18th century. Throughout their long history in Canada, they have been subjected to discrimination and prejudice based on their differences in appearance and culture from the white majority. Racism against Asian Canadians has manifested through discriminatory voting laws, exclusionary immigration policies and forced relocation and internment (see also Right to Vote in Canada; Immigration Policy in Canada). Hate crimes against Asian Canadians are ongoing.

Discriminatory Voting Laws

In 1872, the government of British Columbia amended The Qualification and Registration of Voters Act, which barred Chinese Canadians and Indigenous peoples from voting in provincial elections (see Right to Vote in Canada). This amendment was part of a plan to safeguard political and economic power among white residents. In 1895, the government of British Columbia passed a similar law, the Provincial Voters’ Act Amendment Act, 1895. This legislation stripped Japanese Canadians from the right to vote. This act would be followed by another amendment in 1907, which deprived South Asian Canadians from the right to vote in provincial elections.

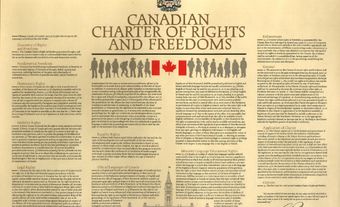

At the federal level, the Electoral Franchise Act, 1885 barred Chinese Canadians from voting in federal elections. The amended Electoral Franchise Act, 1898, allowed provinces to draw electoral lists, but did not permit them to disenfranchise citizens who were qualified to vote. The Act of 1898 allowed Asian Canadian citizens to vote in federal elections, even if they were barred from voting provincially. Voting rights changed with the Dominion Elections Act of 1920. Under this Act racial groups excluded from provincial franchise would also be excluded from federal franchise. After the Second World War, Chinese Canadian veterans fought for their right to vote (see Chinese Canadians of Force 136). After a long fight, they were granted the right to vote in Canadian elections in 1948. The same year, South Asian Canadians received the right to vote, followed by Japanese Canadians in 1949.

Did you know?

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Asian Canadians living in British Columbia were unable to access certain employment and housing opportunities. Laws, such as the 1897 Inspection of Metalliferous Mines Act, excluded Chinese and Japanese workers from working in the metal mining industry. Similarly, the absence of safeguards meant that property owners could refuse to rent to Japanese and South Asian residents (see Racial Segregation of Asian Canadians).

Exclusionary Immigration Policies

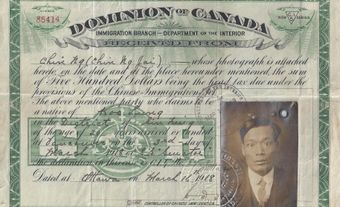

In 1885, amidst rising anti-Asian sentiment in Canada, the Chinese head tax levied under the Chinese Immigration Act (1885), came into effect. This law forced Chinese people who wished to enter Canada to pay a $50 tax. The goal of the tax was to hinder Chinese immigration to Canada. In 1903, the federal government increased the fee to $500, an amount that equaled two years of salary for a Chinese man of the time.

Despite the extremely high cost, the head tax did not deter Chinese immigration and it was replaced by another restrictive law in 1923, the Chinese Immigration Act. This Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, barred Chinese people from immigrating to Canada. The exceptions included students, merchants (excluding laundry, restaurant and retail operators), diplomats and Canadian-born Chinese returning from education in China. This law greatly disrupted the lives of the Chinese communities present in Canada at that time. Mostly composed of men who left families back in China, these communities lacked children and women. They became known as “bachelor societies” where these men came together to support and socialize with each other to combat loneliness. The first Canadian lawyer of Chinese origin, Kew Dock Yip, lobbied to repeal the law. The Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 would finally be repealed in 1947, after it succeeded in restricting the number of Chinese immigrants to a few dozen. On 22 June 2006, Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued an apology to Chinese Canadians for the head tax and the Chinese Immigration Act. The apology also included financial compensation to individuals who paid the tax or to their spouses. On 15 May 2014, British Columbia Premier Christy Clark also issued an apology to Chinese Canadians for the historical wrongs of past provincial governments.

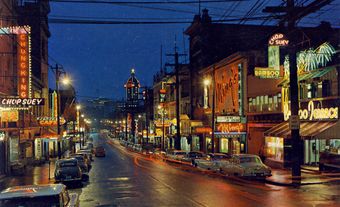

Japanese Canadians also faced immigration controls. In 1907, violent riots targeted Chinese and Japanese neighbourhoods in Vancouver. In 1908, amidst rising anti-Asian hostility in British-Columbia, Canadian Minister of Labour Rodolphe Lemieux and Japanese Foreign Minister Tadasu Hayashi negotiated a gentleman’s agreement that curbed Japanese immigration to 400 people a year. In subsequent years, this agreement was reduced to 150 people a year, but since the agreement only targeted Japanese men, their wives immigrated in large numbers to Canada. Their arrival contributed to the increase of the Japanese diaspora.

Also in 1908, following the violent protests against Asian immigration in Vancouver, the federal government passed An Act to Amend the Immigration Act so that it required all immigrants to arrive on Canadian shores by a continuous journey from their country of origin. This law was meant to target immigrants from India and Japan, as there was no continuous boat service from India or Japan to Canada at the time. Gurdit Singh, a Punjabi entrepreneur, sought to help Sikh and South Asian people immigrate to Canada. He chartered the Komagata Maru across the Pacific. The ship landed in Vancouver’s harbour on 23 May 1914, with its passengers expecting to be able to enter the country. However, Canadian immigration officials denied the passengers the right to land, forcing them to live on strict rations of food and water for several weeks. The passengers challenged this decision in court but lost and were forced to return to India. Upon arrival in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta), British authorities who suspected the passengers to be revolutionaries shot 16 of them dead. More than a century later, on 18 May 2016, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau formally apologized for the Komagata Maru incident.

Japanese Internment

On 7 December 1941, Japanese forces bombed Pearl Harbour in Hawaii, a catalyst that made Canada declare war on Japan. Despite the absence of evidence about the threat Japanese Canadians posed to national security, the federal government used the War Measures Act to send 90 per cent of the Japanese Canadian population, roughly 21,000 men, women, and children, into crowded internment camps (see Internment of Japanese Canadians). The prisoners were relocated far from their homes and sent to do hard labour, roadwork, and sugar beet planting. Their belongings were also seized and sold by the federal government to fund the cost of their internment. After the end of the Second World War, Japanese Canadians were prohibited from returning to British Columbia, where most of them lived prior to the war. Approximately 4,000 Japanese Canadians were deported to Japan. 66 per cent of those deported were Canadian citizens by birth or naturalization. Many of them had never been to Japan. It was only on 1 April 1949 that Japanese Canadians were allowed to move freely again across Canada. On 22 September 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney formally apologized and provided compensation on behalf of the federal government for its actions during the war.

Contemporary Racism

Racism against Asian Canadians continues to this day. The model minority myth and stereotype is one example. This stereotype depicts Asian Canadians as studious, hardworking and as economically prosperous. The model minority myth also compares Asian Canadians to other racialized communities. In this view, some racialized communities face fewer barriers due to perceived attributes while others do not. This stereotype of Asian Canadians persists despite wide income inequalities within the community and continued systemic discrimination. For instance, the racism Asian Canadians experienced during the SARS outbreak (2003) and the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-) are evidence that discrimination against Asian communities remains a lived reality for many. (See also Pandemics in Canada.) During the SARS outbreak, multiple reports detailed Asian Canadians being shunned by others, being targeted by hate groups and being depicted as dirty. Similar incidents occurred amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, when Asian Canadians reported more hate crimes committed against them. A 2021 analysis of police-reported hate crimes found that when compared to statistics from 2019, hate crimes against East Asian and Southeast Asian populations increased by 301 per cent in 2020 (the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic).

Another example of racism against Asian Canadians includes Temporary Foreign Worker Programs, which lets employers bring in foreign nationals, especially as low paid agricultural workers and nannies (see also Domestic Service (Caregiving) in Canada). These migrants, often from the Philippines, have fewer rights than equivalent workers not in the program (see also Filipino Canadians).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom